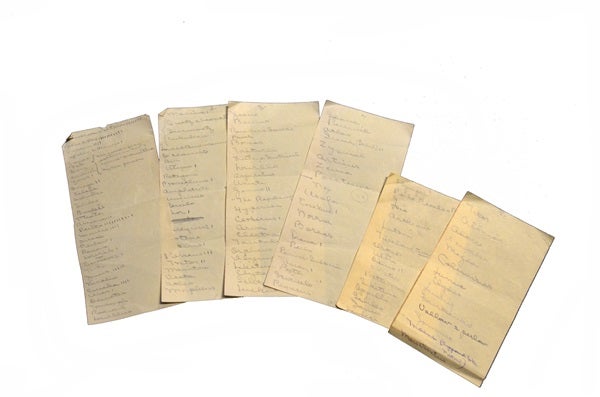

This correspondence, much of it now preserved in Lowell’s new Putnam Collection Center, offers invaluable insight into the issues and prevailing thoughts of the day while also revealing an intimate glimpse at the personalities of many of the individuals who submitted ideas.

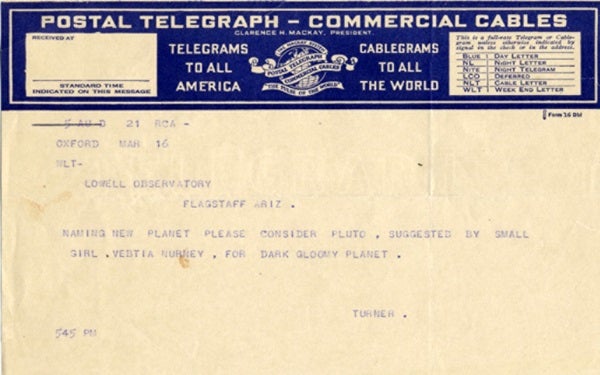

One of those suggestions came from Venetia Burney, a schoolgirl from England who enjoyed learning about mythological characters. On the morning of March 14 while Venetia ate breakfast, her grandfather read to her a newspaper account of the planet’s recent discovery. After thinking about the news and reflecting on her knowledge of mythology, she said Pluto, the god of the distant, cold underworld, was an appropriate name for this dark and gloomy place. Her grandfather sent her suggestion, unknown to Venetia, to the British astronomer H. H. Turner, who in turn shared it with Lowell Observatory.

This note would be one of hundreds received by the observatory but stands alone in importance, as indicated in the last paragraph of the May 1, 1930, Lowell Observatory Circular that served as Pluto’s christening announcement to planet Earth. Lowell Director Vesto Melvin (V. M.) Slipher wrote, “It seems time now that this body should be given a name of its own. … Pluto seems very appropriate and we are proposing to the American Astronomical Society and to the Royal Astronomical Society that this name be given it. As far as we know Pluto was first suggested by Miss Venetia Burney, aged 11, of Oxford, England.”

That part of the naming story is well documented in history books and often encompasses the whole tale. However, it is only the misleadingly brief and streamlined conclusion. In fact, the seven weeks between the March 13 announcement of the planet’s discovery and the May 1 naming declaration were frenetic for Slipher and his colleagues. While they tried to focus on astronomical issues relating to the new planet, such as an orbit determination, the public distracted them with surging demands of what to call it.

Media bombarded Lowell staff with inquiries about the name while letters and telegrams poured in from individuals and organizations with often strongly opinionated proposals. This interest spiked even higher when a reporter misquoted Lowell trustee Roger Lowell Putnam as saying the observatory would welcome suggestions for the name. Publications from the Boston Herald to the San Francisco Daily News, Popular Science Monthly to The Christian Science Monitor carried this story, prompting even more people to join the planet-naming craze.

Newspapers and other entities also began holding contests. Monckton Dene of South Haven, Michigan, wrote four different letters to the observatory hoping to enhance his odds of winning a $5 prize. The Paramount Theater in New Haven, Connecticut, ran a naming contest in conjunction with the local paper. Paramount’s advertising manager, Ben Cohen, wrote a more self-aware letter to the observatory: “The sponsors were not so presumptuous as to promise that the winning name would be given to the new planet. They did promise, however, that the winning names would be forwarded to you for your consideration. Therefore, we respectfully submit to you the contest-winning name for the new planet representing the choice of 200,000 people: Minerva.” Meanwhile, Delia Grace Valancourt of Champaign, Illinois, informed the observatory that she had won a similar challenge held by the Chicago Herald and Examiner for her suggestion of Athena, Minerva’s Greek counterpart as the goddess of wisdom.

The proposers

Urged on by the papers and contests, the suggestions swelled. The precise number of letters and telegrams that swamped Lowell is lost to history. But the observatory received hundreds of them, with some 150 offering the name Pluto, according to a note preserved from Lowell’s secretary, though most of these are nowhere to be found in the archives. With the circus-like atmosphere surrounding the naming, one can imagine much of this correspondence was simply thrown away.

More than 250 letters remain. Many of their authors added fragments of biographical information, so we know they ranged in age from 11 to 78 and included at least 117 men and 86 women. The pool of proposers consisted of students and teachers from elementary school through college, attorneys, ministers, a United States senator, and even a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Navy.

The letters and telegrams came from 37 of the then-48 states (plus the Alaskan territory), with the most from Massachusetts (49), New York (36), and Pennsylvania (24). Suggestions also arrived from Canada, Germany, Korea, England, and Mexico. They proposed a total of 171 different names, with 13 listed at least five times. Ancient deities dominate this list, following the tradition of planet naming. Of these, six are male and four are female. Many of the latter suggestions came from the increasingly vocal female population, whose status in society was enjoying dramatic improvement at the time. One letter suggested six possibilities (Athena, Juno, Psyche, Circe, Cassandra, and Atalanta) and was signed, “Star-rover, She is not a Feminist.” The author wrote, “For ages men have been the Lords of Creation. Now that women are striving for the top o’ the world it would be regarded as a compliment to the sex to give the new planet a feminine name. It might encourage further exalted aspirations.”

A new era

Another theme of the times, the pursuit of peace, stands out thanks to the multiple suggestions of Pax and Peace. Walter Niehoff, a student at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, compellingly captured this sentiment in his letter to the observatory: “The centuries of the past have been stained with the blood of many dreadful wars. Now the world is experiencing a great change. We are in the beginning of an era that shall be known to our posterity as the beginning of the solution for perpetual world peace. The eyes of all men are now looking toward that goal with a hope as never before.”

Literature, both ancient and modern, inspired some suggestions. Ralph Magoffin of New York City hearkened back centuries with Vergilius, in honor of 1930 being the 2,000th anniversary of the Roman poet Virgil’s works. From more contemporary times, T. Horan of Dalton, Georgia, proposed the awkward-to-pronounce Poictesme, from James Branch Cabell’s then-popular but since-faded book, Life of Manuel.

Perhaps the most fascinating look into the public consciousness of 1930 can be seen in the hodgepodge of names that defy any other classification. Howard Carter’s 1922 discovery of the tomb of King Tutankhamun was still in the mind of Josephine T. of Harbert, Michigan, when she suggested Shu, the Egyptian god of the atmosphere, “as recently found by Mr. Howard Carter in the annex of the Tutankhamun tomb.” Even Prohibition, begun in 1920 but winding down by 1930, made an appearance in the name game. Philip Bowman of Annapolis, Maryland, suggested Bacchus, the Roman god of wine-making, as “typical of the age we live in.” The Literary Magazine suggested, “For this notable cosmic catch completing the big-league planetary nine, it would be fitting to call the starry outfielder Babe Ruth.” Ruth was then near the end of his baseball career but still a larger-than-life figure.

“The Planet Speaks”

“Tom Boy” “Tom Boy”

Let it be my name

Surely Mr. Tombaugh

Beats in this game.

Playing “Hide and seek”

I often have thought

I, should like to be

discovered

By one self-taught.

Let the joyous tidings

Ring the world around

“Tom Boy” “Tom Boy”

The latest Planet found.”

One of the cutest ideas came from Karl Underhill of New Hampshire. He wrote, “If I had discovered the new trans-Neptunian planet I would name it Jean after my two-year baby girl. I do not know the definition of the name Jean but it means everything to me. This letter is not a crank.”

While many of these suggestions undoubtedly made for good reading, the Lowell staff ultimately chose Pluto. Putnam gave a press statement explaining the decision to go with a Roman god, in accordance with the other planets. He said, “There have been many suggestions which have been weighed and sifted, and suitable ones were narrowed down to three — Minerva, Cronus, and Pluto.” Minerva was the staff’s first choice but since an asteroid already bore the goddess’s name, they decided on Pluto, “the god of the regions of darkness where X holds sway.” Putnam pointed out that Pluto’s two mythological brothers, Jupiter and Neptune, were already represented by solar system planets. “Now one is found for him [Pluto] and he at last comes into his inheritance in the outermost regions of the Sun’s domain.”

Eighty-five years after Pluto’s discovery and naming, public fascination with this icy body remains strong. These days, instead of suggesting names for the body itself, people are thinking of names for Pluto’s geographical and geological regions, again pulling ideas from mythology, pop culture, and the real scientists and visionaries involved with the Pluto system. What will future generations glean from the current wave of naming choices? Whether because Pluto was long considered the only planet discovered in the United States, or because so many people regard it as an underdog, it remains beloved in the hearts of many in the population. Given this warm regard, plus the heart-shaped region the New Horizons team imaged and later dubbed “Tombaugh Regio,” perhaps Solomon Berman of Washington, D.C., writing to the observatory in 1930, offered the best and most prescient name: Amor.