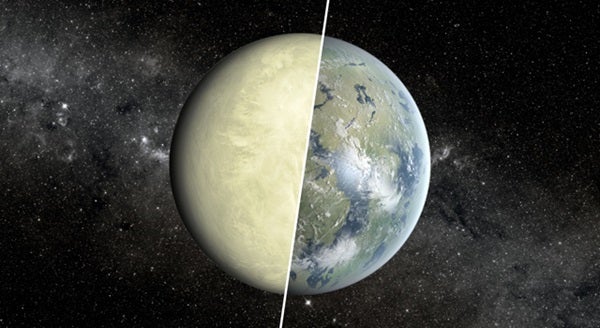

How? Long before scientists hunted for a world similar to Earth around other suns, one planet in the solar system was already referred to as Earth’s twin. Venus has nearly the same radius, mass, and composition as our planet, and lies just outside the solar system’s habitable zone. In the past, it may have had an ocean.

Today, there’s no sign of liquid water. Venus is an overheated world, with temperatures climbing to 864 degrees Fahrenheit (462 degrees Celsius). Lead melts on the surface of the planet, making it a challenge to explore. But understanding what makes a world into a cool, refreshing Earth or a hot, hellish Venus means understanding just why Earth’s ancient twin is so different today.

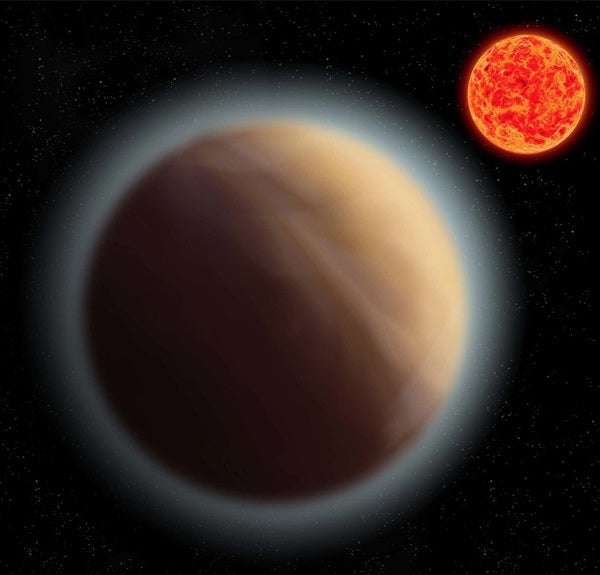

“Everything we know about planets comes from in situ data from within our own solar system,” says Stephen Kane. An exoplanet hunter at the University of California, Riverside, Kane has long been concerned that many of the planets beyond the solar system that have been dubbed Earth-like by scientists may in fact be more Venus-like — exoVenuses. The best way to fix that, he argues, is to return to visiting Earth’s twin.

“We have two examples of Earth-size planets [in our solar system], and one of them, we know very little about,” Kane says. And that needs to change.

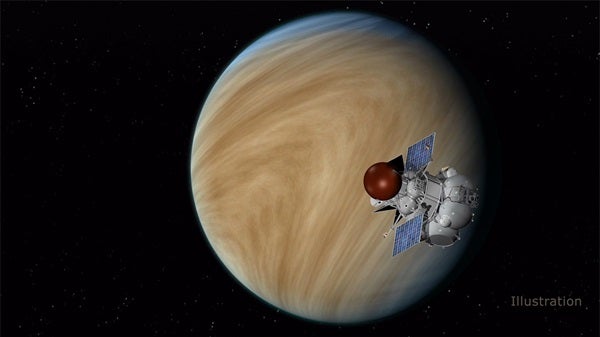

In the 1970s and early 1980s, the Soviet Union sent several landers to the surface of Venus. Although designed to last only half an hour, some spacecraft survived nearly two hours after landing. Since the destruction of the last Russian juggernaut, Venera 14 in in 1982, no lander has touched down on the hot planet.

Kane laments the gap. “There have been great increases in technology to allow a spacecraft to survive longer than Venera did 40 years ago,” he says. He argues that we should be striving to better understand the geology, the seismology, the volcanic history, and the soil on the planet, among other things.

“All these kinds of things are crucial in us being able to understand Earth-like exoplanets,” he says.

NASA will be launching its Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) in April 2018. TESS will be able to spot even more exoplanets, many of them Earth-sized. Weeding out the ones that are potentially habitable, like our own planet, versus those that are hot messes like Venus requires a better understanding of the second planet from the Sun. Similarly, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) was scheduled to launch in the spring of 2019, though new delays have now pushed that date backward to 2020. JWST will help to characterize exoplanet atmospheres. A better understanding of what’s going on in the air above Venus will help researchers better determine whether the planets they see have comfortable atmospheres like Earth, or greenhouse atmospheres like Venus.

He points to Mars researchers, who have a wealth of data at their fingertips from rovers, landers, and orbiters.

“[The Venus community] looks with envy upon their Martian colleagues,” Kane says.

Mars is important for astrobiology in the solar system since it represents the limits of planetary habitability around the Sun. However, for astrobiology studies outside of our solar system, he says that the focus will undoubtedly focus on planets similar in size to Earth, due to both anthropic reasons and current detection biases. This means that the study of Venus is far more relevant to the search for life in the universe since “it serves as a warning of how an Earth-size planetary evolution can go catastrophically awry,” Kane says.

Kane presented his research in December at the American Geophysical Society in New Orleans, Louisiana. He is the lead author of a paper posted on the preprint server arXiv, with the idea of spurring further exploration of Venus.

“What we need to be doing is squeezing every last drop of in situ data from our solar system that we can,” Kane says.

Would you like to learn more about our solar system’s hottest world? Check out our free downloadable eBook: Venus and Mercury: Hot, volatile planets.