A professor and his student from the University of Rochester in New York conclude that only “strongly interacting” binary stars — or a star and a massive planet — can feasibly give rise to these powerful jets.

When these smaller stars run out of hydrogen to burn, they begin to expand and become asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars. This phase in a star’s life lasts at most 100,000 years. At some point, some of these AGB stars, which represent the distended last spherical stage in the lives of low mass stars, become “preplanetary” nebulae, which are aspherical.

“What happens to change these spherical AGB stars into nonspherical nebulae, with two jets shooting out in opposite directions?” asked Eric Blackman from the University of Rochester. “We have been trying to come up with a better understanding of what happens at this stage.”

For the jets in the nebulae to form, the spherical AGB stars have to somehow become nonspherical, and Blackman says that astronomers believe this occurs because AGB stars are not single stars but part of a binary system. The jets are thought to be produced by the ejection of material that is first pulled and acquired, or accreted, from one object to the other and swirled into a so-called accretion disk. There are, however, a range of different scenarios for the production of these accretion disks. All these scenarios involve two stars or a star and a massive planet, but it has been hard to rule any of them out until now because the “core” of the AGBs, where the disks form, are too small to be directly resolved by telescopes. Blackman and his student, Scott Lucchini, wanted to determine whether the binaries can be widely separated and weakly interacting, or whether they must be close and strongly interacting.

By studying the jets from preplanetary and planetary nebulae, Blackman and Lucchini were able to connect the energy and momentum involved in the accretion process with that in the jets — the process of accretion is what, in effect, provides the fuel for these jets. As mass is accreted into one of the disks, it loses gravitational energy. This is then converted into the kinetic energy and momentum of the outflowing jets, which is the mass that is expelled at a certain speed. Blackman and Lucchini determined the minimum power and minimum mass flows that these accretion processes needed to produce to account for the properties of the observed jets. They then compared the requirements to specific existing accretion models, which have predicted specific power and mass flow rates.

They found that only two types of accretion models, both of which involve the most strongly interacting binaries, could create these jetted preplanetary nebulae. In the first type of model, the “Roche lobe overflow,” the companions are so close that the AGB stellar envelope gets pulled into a disk around the companion. In the second type of model, or “common envelope” model, the companion is even closer and fully enters the envelope of the AGB star so that the two objects have a “common” envelope. From within the common envelope, high-accretion-rate disks can either form around the companion from the AGB star material or the companion can be shredded into a disk around the AGB star core. Both of these scenarios could provide enough energy and momentum to produce the jets that have been observed.

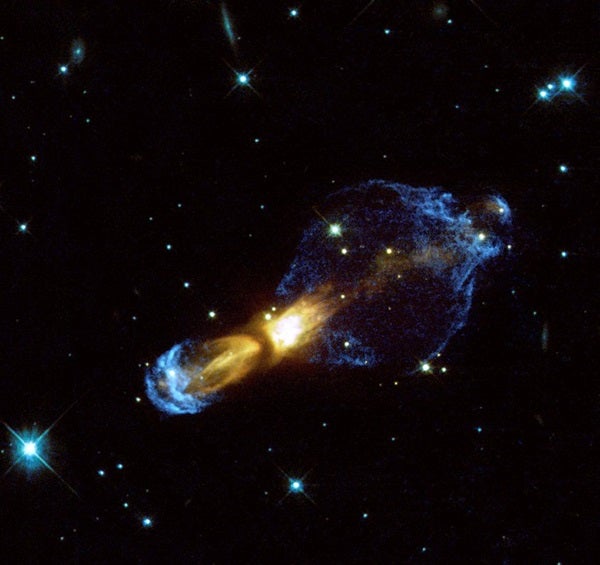

The name planetary nebulae originally came from astronomer William Herschel, who first observed them in the 1780s and thought they were newly forming gaseous planets. Although the name has persisted, now we know that they are in fact the end states of low-mass stars and would only involve planets if a binary companion in one of the accretion scenarios above were in fact a large planet. “Preplanetary” and “planetary” nebulae are different in the nature of the light they produce — preplanetary nebulae reflect light, whereas mature planetary nebulae shine through ionization (where atoms lose or gain electrons). Preplanetary nebulae shoot out two jets of gas and dust, the latter forming in the jets as the outflows expand and cool. This dust reflects the light produced by the hotter core. In planetary nebulae, thought to be the evolved stage of preplanetary nebula, the core is exposed and the hotter radiation it emits ionizes the gas in the now weaker jets, which in turn glow.