The massive O-type stars, more than 16 times as heavy as our Sun, have short but dramatic lives. During their most stable phase on the so-called main sequence, they have surface temperatures of more than 54,000° Fahrenheit (30,000° Celsius) — the Sun’s surface is about 9900° F (5500° C) — are strong sources of ultraviolet light, and emit copious material in a powerful wind.

All of this shapes their surroundings. The O-type stars heat any interstellar gas in their vicinity, creating bubbles that act like snow ploughs sweeping up surrounding colder material. In these regions, where gas is compressed, large numbers of new stars are seen forming, so many that scientists argue that the O stars drive star formation.

In his new work, Balfour has tried to test this idea by simulating the way gas behaves over a period of 1.6 million years, a simulation that took several weeks of computing time to calculate. His model explored what would happen when a massive star forms in a smooth cloud of gas that is already collapsing under its own weight.

Light from the O-type star creates a bubble in the cloud as expected, but its future can follow one of three paths. It may expand forever; expand, contract a little, and then become almost stationary; or expand and then contract all the way back to the center of the cloud. Balfour found that only the second case leads to prolific star formation — and even then only under very specific conditions.

“If I’m right, it means that O-type and other massive stars play a much more complex role than we previously thought in nursing a new generation of stellar siblings to life,” said Balfour.

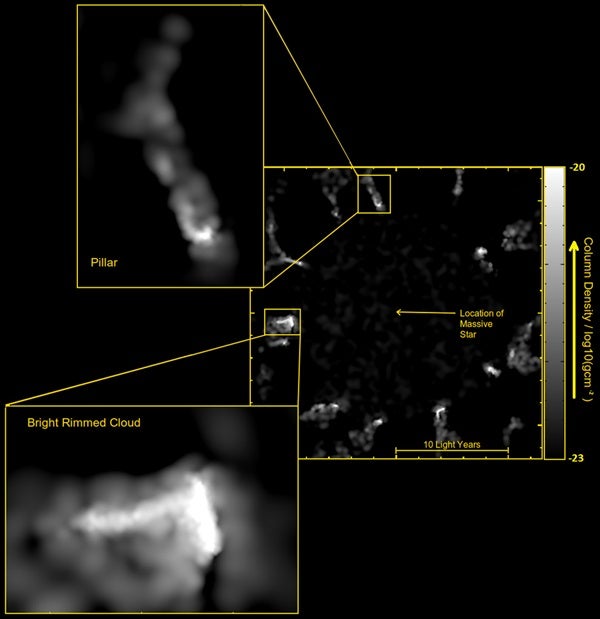

His model also neatly replicates the bright rims and pillars seen in the Hubble image, which seem to form naturally along the outer edge of the bubble as it breaks up.

“The model neatly produces exactly the same kind of structures seen by astronomers in the classic 1995 image, vindicating the idea that giant O-type stars have a major effect in sculpting their surroundings,” said Balfour.