In many ways, Tony Fadell built the digital world we live in.

At the turn of the millennium, his efforts to build a pocket-sized, hard-disk-based device that could hold 1,000 songs in MP3 format caught the attention of Apple. Within months, he had been hired by the firm, and less than a year after his first phone call with Apple, the iPod had been revealed and was shipping to customers.

Fadell then went on to play a key role in the creation of the iPhone, overseeing its hardware. And after he decided in 2008 to leave Apple, he co-founded Nest Labs, reinventing the thermostat and ushering in the era of the internet-connected home.

But after leaving Nest in 2016, Fadell pivoted and started Build Collective — a fund that advises and invests in startups building solutions to address some of the world’s biggest problems, including the climate crisis.

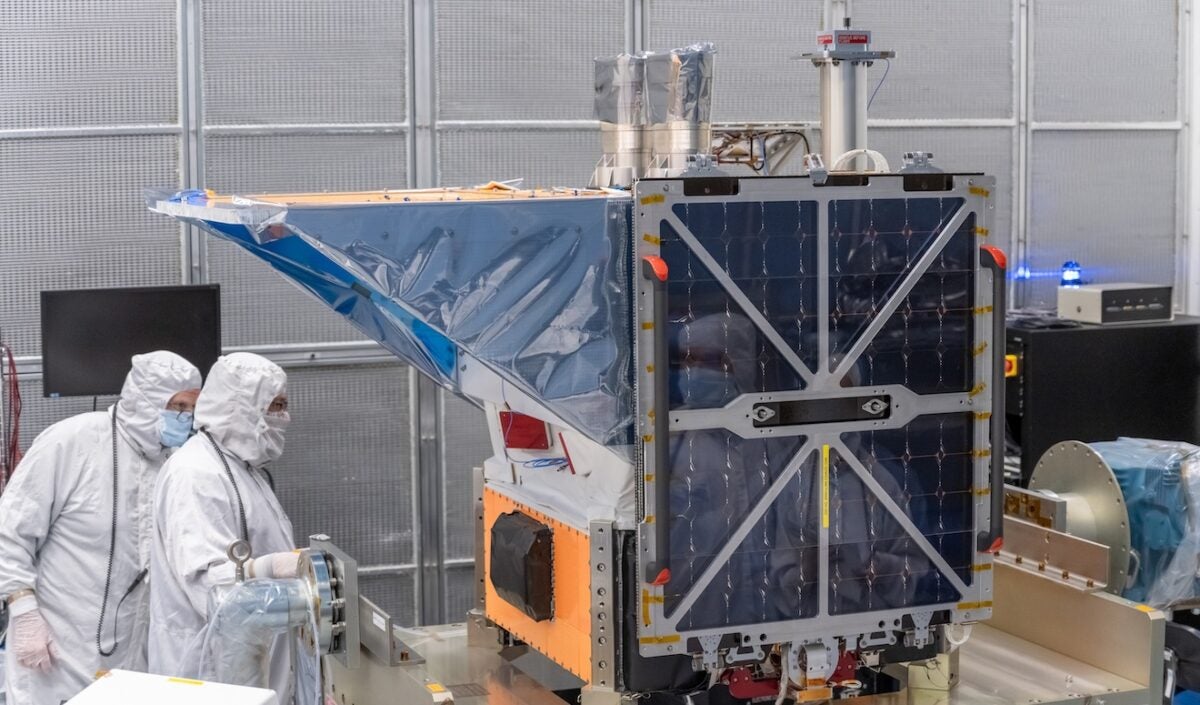

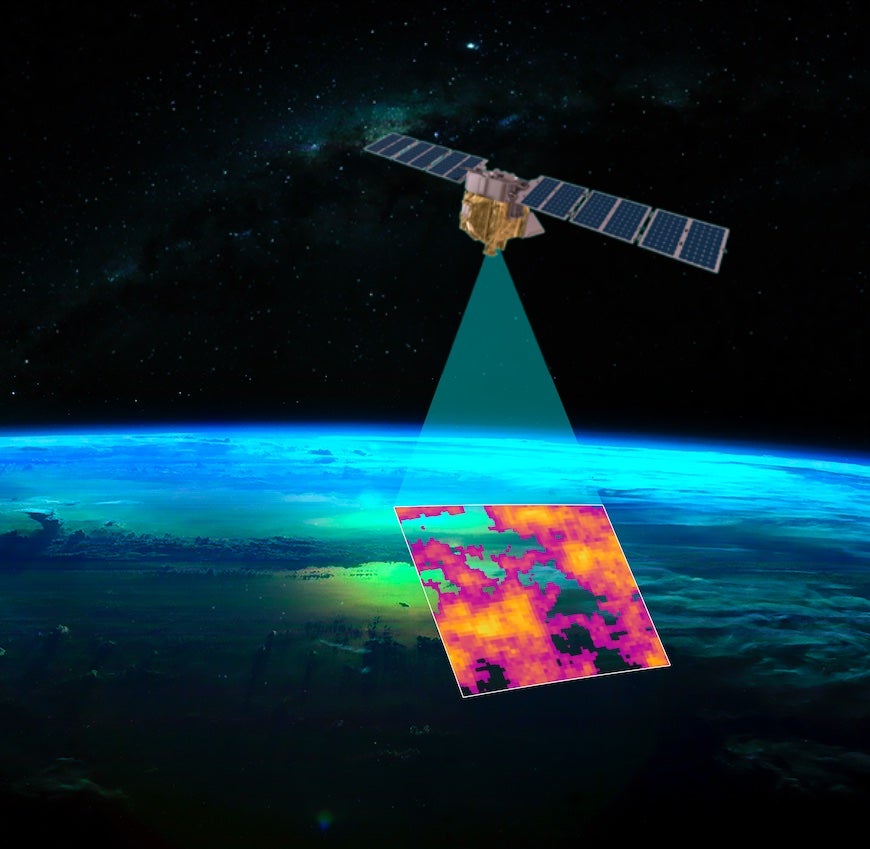

He was also instrumental in the creation of MethaneSAT, the most ambitious satellite to ever be built and run by a nongovernmental organization (NGO). Operated by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) in collaboration with the New Zealand Space Agency, the satellite launched March 4, 2024, to monitor emissions of methane — a greenhouse gas estimated to trap 28 times as much heat as carbon dioxide over the molecules’ lifetimes.

Fadell spoke with Astronomy about building climate solutions, the relationship between space exploration and environmentalism, and what gives him hope in the face of the climate crisis.

How do you see the climate state of play right now? What’s the scale of what needs to be done to reign in global warming?

The first thing is, this has been a problem that has been created over the last 150 years. But the scale of the change we need now cannot take place over another 150 years.

We have to change everything all at once. We have to get to Industrial Revolution 2.0, which means everything that flies, floats, rides on the land, it all needs to change. How we do agriculture, materials, textiles — every single thing that came from Industrial Revolution 1.0 needs to be touched in 2.0, and a lot of it very dramatically.

That said, I have been investing and working in this space since about 2008, when I had kids — post-iPod, post-iPhone, kind of Gen-1 Nest. And what I have seen since then is that we really do have the technologies to abate and stop emissions of greenhouse gases like CO2 and methane. And in almost all cases, it’s more economical and better for the businesses who would implement them, from a return-on-investment perspective.

The issue is the high amount of capital and people and investment that is required to change the fundamental economic powers that be, whether that’s a government or the champions in any one industry. Nobody wants to change because they want to protect their spot.

So, we have the technology we need, yet we have this inability to want to make the change — even though it’s an existential crisis — because people want to continue to protect themselves. They understand that they have something to protect in the short-term — and the long-term, they don’t want to see.

And so, we have a problem of will, not a problem of technology. It’s human will, to be able to make those changes.

The problem that we have in democracies is that we have factions and no one wants to compromise in the middle. And so, it takes real adults in the room who all agree there’s a problem.

At the corporate level, even though it’s a better outcome businesswise, it means compromising the position that you’re in. Investors and stakeholders don’t want the state of play to change, or lose their valuable stock because they’re going to have to really ramp up their spending to make the changes necessary.

And then governments, for the most part, in democracies — which are, especially in the U.S., driven by political donations — are aligned with these large corporate interests who do not want things to change because that means work.

These people have been maintainers. They are not builders. They’re very different. So, we need the right incentives from government to encourage more and more builders to do these things while not continuing to subsidize the old habits that have gotten us into this problem.

Now, we’re getting pointed in that right direction. We’re seeing that change in certain places, like Norway — it’s incredible what Norway’s done. Now, on the road, there are more fully electric vehicles than there are gas-powered cars. And that’s on the road, not being sold. What’s being sold is over 90 percent electric. And it’s not just electric cars, they have excellent mass transit as well.

So, it can be done. It’s just a matter of the will to do so and to make those changes and for people to understand that it’s going to impact things, but that it’s for the greater good of the planet — as well as for their next generations that they spend and invest so much time and care in to raise.

After leaving behind tech products like the iPhone and Nest, why did you move into the climate space?

I’ve always cared about the planet. My grandfather taught me how to garden and trim trees and was always taking me out in nature. So I always had a love of it — it really is me, it’s in my person. And I woke up to the issue really in the mid-2000s, around the time of Al Gore’s documentary, An Inconvenient Truth.

I also started seeing the problem when I was working on the iPod and iPhone and traveling to China. I saw how China was just gobbling up the earth that they had. Every time I went, I’d be like, “Oh my God, all this has changed, all this has changed.” And I thought, “Wait a second, where’s the balance in all this?” I’m not saying that they shouldn’t do what they should do in China, I’m just saying that we need to have a bigger perspective on this.

So I was hearing about the problem, I was seeing the problems being created, and I thought, “How do I get involved?” And when I started learning more, I was like, “Wow, there is amazing technology that we need to deploy. And these are actually more profitable businesses when you do it right. Wait a second, it all aligns, it can be a win-win-win.” And with the scale of the change — larger than the first Industrial Revolution — I thought, “Yes, we can do this.”

If I had been around at the Industrial Revolution at the beginning, I would have been like, “I want to be part of this, everything’s going to change.” Well, guess what? We have the exact same thing, and the incumbents aren’t the ones who are going to necessarily fix this. This is not a little thing, this is a huge thing, transformative in every single nook and cranny of our industrial world, and to me, that’s opportunity.

One thing you’ve helped to build recently is MethaneSAT. Can you talk about how you got involved?

The Environmental Defense Fund called me because I had been working with them on other projects from the perspective of a donor. This was the first time they were trying to launch a satellite. That’s a very, very high-capital expenditure, and you’ve got to maintain it for 10, 15, 20 years while it’s in space. It’s not just a one-time expense, it’s a continual annual expense. And so they wanted to do something that no NGO had ever done before — not to this level.

So, they were asking for advice on building a business, how to maintain it and sustain the satellite after it launched. There were a lot of brainstorming sessions to figure out the business model — how to get an NGO to have a for-profit business to pay for it while still making the data available for free, because that’s what the NGO’s mission is.

And so, I got involved very early on because Fred Krupp, who runs EDF — and he’s been a visionary for more than 30 years on climate — asked for my help. And then we got other like-minded technology and business people around the table to try to help solve for this.

And we’ve launched the satellite and it’s up and it’s working and it just started reporting data after the calibration period in August. It is doing actually better than we thought it was going to do. It’s exceeding expectations for numerical quantification of these leaks.

What’s the significance of MethaneSAT, and how do the different pieces of this business model work?

The first and most important thing is having a third-party source of truth — someone that’s trusted, not paid off by a governmental agency or an industry agency or whatever else. This is a third-party eye in the sky that is not beholden to any one group except the population at large.

Then after that, we have different levels of data. There’s raw data that you can get from the satellite. And then there are all the other levels of turning that data into information. And because that takes compute [computing resources] and that takes real work and energy to create, those levels of information become our tools from which to derive revenue.

We can offer this information to third parties who are interested, whether that’s governments, whether that’s other NGOs who are fighting climate change, whether that’s industries — either industry groups or individual industries like oil and gas, obviously, or agriculture. Stock traders, too — they want to know if there’s going to be fines levied against oil and gas or agriculture, because those are the main ways methane is produced.

So going from raw data to information, that’s where value is achieved. And because we know the satellite and how it works, we can turn the raw data into discrete information.

You can have the raw data for free, and anyone can get that. But as we turn it into information, then it becomes more valuable. And that allows us to then use it for marketing purposes — and for disclosure purposes.

It’s the first time it’s ever been done. And that’s what’s so extraordinary about what the EDF and Fred have pulled off.

In spaceflight, we used to only talk about government agencies, right? Then we began talking about commercial spaceflight. And now there’s a third space sector, of NGOs. And I hope it’s inspired more NGOs to want to do this as well, to put eyes in the sky for whatever else needs to be watched.

There’s obviously a big historical connection between spaceflight, astronomy, and the environmental movement. How do you think about space exploration and how it relates to solving environmental issues here on Earth?

I think there’s two ways of looking at it. You know, I’m fascinated by space because we can go out and look back. There are other people who just want to keep looking out, and not look back.

For me, space is interesting, and there’s all kinds of questions to be asked about the universe. It’s great, and I love reading Astronomy and other things to learn about that stuff, because it’s fun to do. But to me, that is a hobby and not an imperative.

When we’re pointing things back at Earth and they’re eyes in the sky that are helping us to solve problems on Earth, that’s when it gets very interesting for me. That’s when it turns from a hobby into something I will dedicate my time and energy to — to help someone and fund businesses and things of that nature.

I’m not funding the next mission to the Moon or Mars, but I will fund and work on things that are going to help us to improve health, our societies, and our environment here on planet Earth.

How important is it to you for humanity to become a multiplanetary species?

This is how I think about things of that nature: If we’re not healthy in the stuff we’re doing now, don’t distract yourself. If we’re not healthy, why are we doing this? Let’s make sure we’re stable and good here and really do the things we need to get done and not distract ourselves from what’s most important with shiny objects like going to Mars.

The only thing that I thought is really interesting about going to Mars is that, ironically, we’re going to learn how f—— good we have it here on Earth, and how horrible it is to go live on another planet without anything. I mean, Mars has got nothing compared to what we have here. We are living in abundance, incredible abundance everywhere — even in Antarctica, compared to freaking Mars!

So maybe it’ll make us all wake up and go, “This is a lot harder than we thought, and we should appreciate what we have.”

When it comes to spaceflight, I love the fact that the “Earthrise” photograph and these kinds of things can give us perspective on who we are as a species — that is what’s powerful. And not just the wonder and awe of where we are in the universe, which is beautiful, but also the destruction we’re doing to the planet that we don’t know about in our little daily world, versus what’s happening on the planet at scale.

And when you have data transparency and you can start to project those data, you can start to get a whole sense of what’s going on on this planet. I love to see it — not because I love to see maps of things like warming and deforestation, but I love to see it so that it motivates us.

I bet when we bring a global perspective to people, and how we are this virus on this planet, people will go, “You know, I understand I’m going to make my individual change, but man, we really need to get over this issue of collective will to get moving.” And I think that only comes from having a wider perspective. And that comes through education, and education comes through information and data transparency, and that can only be done from these things that are looking back at us.

You’ve written a lot about not just building products, but building teams — teams that have a sense of common purpose. How do we scale that to society writ large, and unite ourselves to solve a global problem like climate change?

It always takes one — one person, one product, one company, one mission. And when someone does something bold, and if that’s successful, that emboldens the others who are around them to go, “Wait a second, they can do that, I know that guy, I knew that girl, I knew that one, they went to school with me, I could do that. If they can do it, why can’t I do it?”

So it takes that movement, and my hope is that we’re going to see a lot more of it — now that we’re at this second or third generation of climate-crisis-focused businesses — that you’re going to see these break out, and they’re going to be unicorns and decacorns [terms for a privately-held company valued at $1 billion and $10 billion, respectively] and all that stuff, and people think, “I want to do that too.”

You know, Nest was that in a way — we were saving energy and saving lives [with the Nest smoke detector], and a bunch of people and startups all spawned up from it. I’m hopeful that we’re going to see another crop, and this is going to be bigger and bolder than ever, and that it becomes this avalanche, snowball effect, that there’s going to be more and more and more.

And so that’s my hope. And the alternative is not to have hope, in which case, you might as well just go to Mars.

So what do you see that gives you hope?

What gives me hope is we have the technology, and we have a new generation of people on this planet who do understand that they’re going to live with these problems that we and our forefathers and mothers created, and they want to do something about it.

And you can see it in many people who are not just rushing to go into banking, or whatever it was in the 80s — you know, quick money. They care about the mission and what they’re working on, what they’re investing their time and energy into. They’re a big force for change inside of organizations, as well as building new ones.

That’s what gives me hope. And in politics — I’m looking around the world and seeing younger candidates. These old, old politicians are aging out, and we’re going to see change.

It’s just, is it going to be soon enough? But we are making more progress than we were five, 10, 15 years ago.

We have to get large institutions and systems to continue to act. The Inflation Reduction Act was a great one. We have to keep the faith and keep on moving and get more eyes in the sky to give us perspective on who we are as a species and what we’re doing to this planet. There are a lot of good people in this world and they want to do the right thing — they just don’t know how.

Look at when COVID happened — we got our s— together, to a certain extent. I’m not saying it was perfect, by any means! But man, the world went, “Oh, we need these solutions — now.” We need that kind of thing for climate change. But we can’t wait and do it at the end. You can’t reverse the effects of climate change when everything is underwater.

You can either be hopeful or not. And I’ve seen so many things to give me hope over the last 15 years. I wouldn’t be having a hopeful conversation with you unless I’ve seen real change and real progress.

Is it enough? No. But could we get there? Well, the trend seems to be going in the right direction.