On a crisp night last fall in the Arizona desert, I stood amid sand and scrub at the intersection of Valencia and Kolb on the outskirts of Tucson and beheld a gleaming gas station.

To say that this coruscating beacon of convenience was well lit would be like calling a dinosaur incinerated by the Chicxulub meteor impact well done. LED lights shed painfully bright white light across the sidewalks and pavement, attracting swarms of desert crickets. Several faulty lights nearby added a dystopian purple haze.

Across the street stood a second gas station — just as large, but with lighting that seemed softer, warmer, and not as glaring.

With me was a small group of dark-sky activists, including John Barentine, a Tucson-based astronomer and consultant on dark-sky issues. From our vantage point, it was obvious which gas station was the larger emitter of light pollution. But, Barentine explained, both buildings met Tucson’s lighting code. I nodded, feeling depressed about the state of artificial light at night, or ALAN.

The threat of ALAN has long been known to astronomers and shows no sign of abating. Not only is it growing, it’s acquiring new forms. Today, you can be far out in wild country and still witness urban light domes and passing satellite constellations looking like moving sculptures in space. And the widespread adoption of cheap and efficient LEDs has allowed blue-white light to spread across the sky like a science-fiction fog.

Perhaps even more unsettling is the growing realization of light pollution’s impacts on ecosystems and even society. Losing dark nights doesn’t just mean losing stars: New research is showing that ALAN can be deadly to animals and harmful to humans.

As a result, light pollution is no longer just a rallying cry for astronomers — it is increasingly recognized as an environmental crisis. This means that astronomers have new allies in the global fight against the light. Arizona — with its historic observatories and tough lighting codes — is just one of many communities on the frontlines.

A snapshot of ALAN

In response to the growing sense of crisis, in June 2023 the journal Science devoted a special issue to light pollution, defining it as “illumination at times and locations that are unnecessary, excessive, intrusive, or harmful.” Sometimes there is too much lighting in one location. Often, fixtures shed light in directions other than down, where it is intended for public safety. Science cites many sources beyond streetlights, including buildings, vehicles, advertising, and sports facilities.

Lighting follows development, explained Amy Oliver, public affairs officer for the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, as she drove us along a dark rural stretch of Pima County. And we saw evidence backing her words: A school we passed had an intensely bright digital sign promoting everything from enrollment days to sporting matches — a glaring presence that temporarily blinded me. Beyond it, the empty sports field’s lights were on.

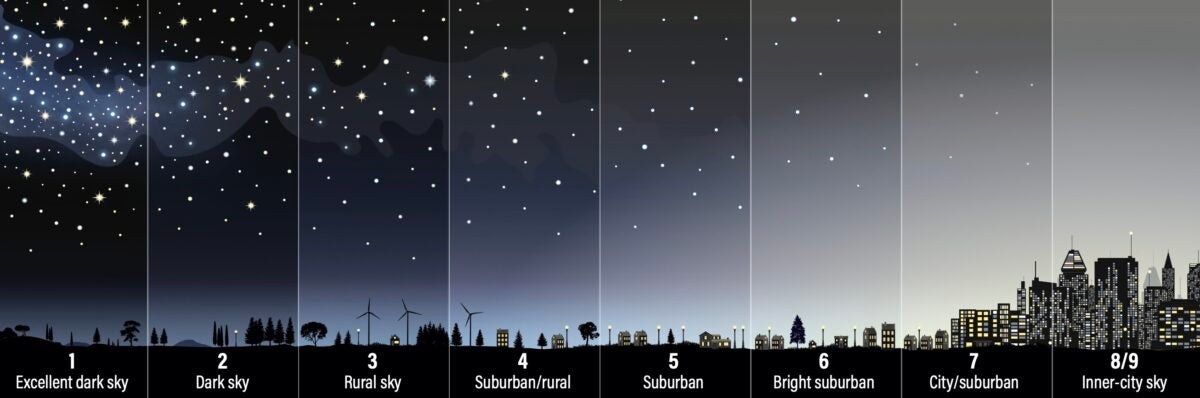

Barentine and co-authors Miroslav Kocifaj and Stefan Wallner explain in the Science special issue that a decade ago, ALAN was increasing globally at an average rate of about 2 percent a year, based on satellite observations of upward-directed light. But, Barentine says, those observations undercount the real change by only considering light that makes it through the atmosphere. A more recent Science study, he says, which doesn’t suffer from the same bias, estimates the sky’s brightness is increasing at about 10 percent each year.

In a 2023 talk, Smith College astronomer James Lowenthal, who heads the light pollution subcommittee of the American Astronomical Society, put the consequences for a naked-eye observer in visual terms: “We’re already losing about one star per day. In a decade, most parts of the United States could have lost thousands of stars from their sky.”

The bad guys … sort of

If there are bad guys in this story, they are ignorance and LEDs — or, more precisely, the latter’s misapplication. While the first is a longstanding foe, the second is a newcomer that has made swift advances. LEDs are everywhere, having proliferated due to their low cost, high efficiency, purported safety benefits, and a global wave of bans on old-fashioned incandescent bulbs. LEDs are supposed to be good for energy budgets and Earth’s climate, but when left unchecked, they produce harsh light that can overwhelm the night sky, polluting more than the lighting it replaced.

Most LED parking lot and streetlight fixtures shine at a correlated color temperature (CCT, which describes the hue of lighting perceived by the human eye) of 3,000 kelvins, bluer than light at 2,700 K — the lowest CCT that manufacturers produce, which is still bluer than the amber glow of older sodium-vapor lamps. For comparison, a CCT of 5,000 K is closer to daylight.

Bluer light, with a higher CCT, is more harmful to astronomy: It has a shorter wavelength, which the molecules in Earth’s atmosphere more easily scatter, washing out more of the sky. For astronomers, this reduces the contrast between their target and the background sky, resulting in “not detecting the object at all or needing either a much bigger telescope or longer exposure time to detect it,” explains Barentine.

Scattering from blue-rich LEDs is a problem even in the Atacama Desert of Chile, home to many of the world’s great observatories. At the seemingly pristine site of the Las Campanas Observatory — home to the twin Magellan Telescopes and the forthcoming Giant Magellan Telescope — half of the background skyglow comes from road lighting 25 miles (40 kilometers) away, according to a 2022 study in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Its authors find that some two-thirds of all large observatories experience skies 10 percent brighter than natural levels, which is the limit for a light-polluted observatory site as defined by the International Astronomical Union and International Commission on Illumination.

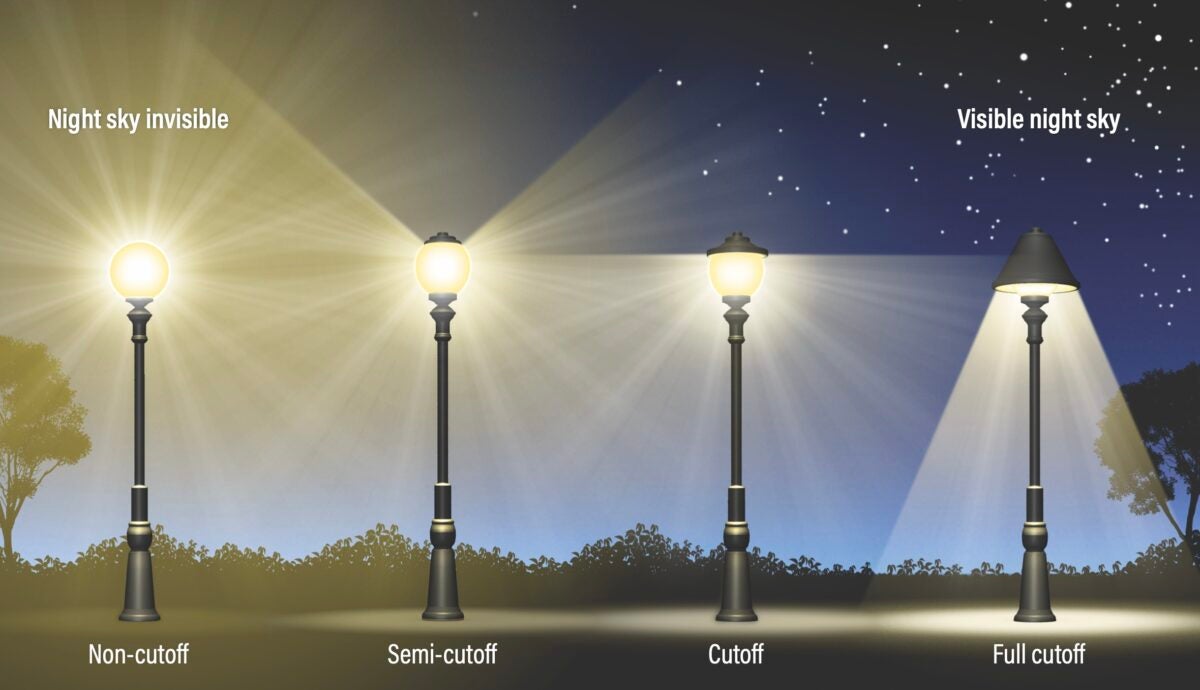

But Tucson has shown that light pollution can be reduced with large-scale public intervention. In 2016 and 2017, 90 percent of street fixtures — nearly 20,000 lights — were replaced with downcast lights, most of which are shielded, meaning the lighting element is inset into the fixture. The lights are set at 90 percent maximum brightness, but dimmed further — down to 60 percent — between either midnight or 3 a.m. (depending on location) and the hour before dawn.

There were no complaints from the public. “Nor has there been an increase in crime or traffic accidents that we can detect in the available data,” Barentine says, as we zip down Aviation Highway. Most residents — including myself — didn’t notice the change at all.

Bye, ALAN

Tucson’s lighting code is already considered strong. In northern Arizona, Flagstaff’s night-sky protection is trailblazing.

Flagstaff is the world’s first designated International Dark Sky Community and home to several astronomical facilities, including Lowell Observatory. It’s often said that Flagstaff and astronomy grew up together: The first pro-astronomy lighting ordinance was passed there in 1958, when famed astronomer E.C. Slipher got the city to ban advertising searchlights.

Now, dark-sky activist and retired astronomer Chris Luginbuhl leads the charge. When we met over lunch at the aptly named Dark Sky Brewing, Luginbuhl noted that Flagstaff is both unusual and an example, in that the city and county government have well-written lighting codes — including enforcement — integrated across departments with buy-in from businesses and the community. According to Tiffany Athol, a senior city planner, Flagstaff allows streetlights only at corners and intersections. Like Tucson, crime has not increased.

I can attest that Flagstaff’s skies are considerably darker than any other city of its size I’ve visited. Surrounding communities in Coconino County have dark skies that any astronomer would envy. And just recently, more restrictions on lighting were added around the U.S. Naval Observatory.

“What’s left to do now?” Luginbuhl says. “Everything.” Flagstaff will continue to grow. Research shows that growth will lead to a 20-percent increase in light pollution over the Naval Observatory, says Luginbuhl. But, he notes, retrofitting old fixtures with updated lighting would cut that increase to 10 percent. He’s now conducting a study to produce an atlas showing the brightness of the night sky around the world, as seen from the ground, if every community followed Flagstaff’s example.

Of course, not every city has Flagstaff’s astronomical heritage and largely sympathetic public. Taking on ALAN around the globe will require nurturing and growing city-dwellers’ willingness to become code-literate — and, perhaps more fundamentally, their sense of personal investment in the night sky. And even in Flagstaff, Luginbuhl often hears residents say they support lighting restrictions because they’re happy to help the astronomers. “But I ask, ‘Doesn’t it matter to you?’ ” he says.

Profound effects

After all, light pollution isn’t just bad for the sky. A growing body of research shows that it’s bad for us, too.

Architect and professional lighting designer K.M. Zielinska-Dabkowska and collaborators write in the Science special issue that “nocturnal light exposure can strain the visual system, disrupt circadian physiology, suppress melatonin secretion, and impair sleep.” Although more research is needed, blue light at night also appears correlated with a rise in cancer risk and may even change our gut microbiome. The American Medical Association already recommends street lighting CCTs be lower than 3,000 K. However, Barentine notes, “it’s very difficult to link outdoor lighting to human health problems” because indoor light likely has larger effects.

Poorly directed and overly bright light can also temporarily blind, reducing safety, especially for drivers suddenly shifting from very bright to very dark environments. At the same time, nighttime lighting brings powerful liberatory benefits, of which dark-sky advocates need to be mindful. The study notes that in rural areas of developing countries, “children often gather in publicly lit areas with streetlights to study and do homework” to avoid unhealthy light sources, like wood fires, at home. Yet such access does not mean we have to pollute the night sky. That’s one of the challenges.

And light pollution affects more than humans. Insects swarm around artificial lights at night because they may confuse them for moonlight, the special issue of Science and a January 2024 paper in Nature find. According to the Science paper, “blue light attracts more insects than the yellow and red parts of the spectrum.” (Bats are also more bothered by blue light than red and may abandon roosts due to human light sources.) Swarming exhausts insects and might be one reason their populations are plummeting. Their decline also affects birds and other creatures who feed on them.

Bright glass buildings are also dangerous to birds. On just one night in October 2023, nearly 1,000 migrating songbirds collided with Chicago’s lit-up McCormick Place Lakeside Center. And newly hatched sea turtles confuse lit beaches for the reflective ocean, drawing them in the wrong direction, often to their deaths.

The U.S. Forest Service has found that deer and mountain lions change their behavior near urban areas. Deer are attracted to light for protection but also forage more quickly, perhaps leading to less nourishment by spending less time looking for food. And attracting large mammals of any kind into urban settings presents dangers to them and to humans.

In addition, rodents and amphibians live shorter, less fertile lives because of ALAN. Even plants change their behavior in response to ALAN, whether holding on to leaves longer in the fall or sending more biomass into leaves instead of roots.

While these accruing negative effects are overwhelming, it does mean new allies in the fight against the spread of excessive blue-white LED light. The Tucson Audubon Society and Sky Island Alliance have helped organize town halls and community meetings tackling light pollution and its impact on biomes around Whipple Observatory, Oliver notes. Whipple stands atop Arizona’s Mount Hopkins in the Santa Rita Mountains, which is home to a fragile and unique “sky island” ecosystem. This year, Whipple — along with DarkSky International’s Southern Arizona chapter, several entomologists, experts from the National Forest Service, and the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation — will launch a light-pollution-monitoring project that includes studying its effects on the local glow worm population.

That more people are seeing light pollution as an environmental cause is a critical development. “We need as many strong voices as possible to share the full story of the impact of light pollution,” Oliver says.

Constellations of our own making

All that’s just here on Earth.

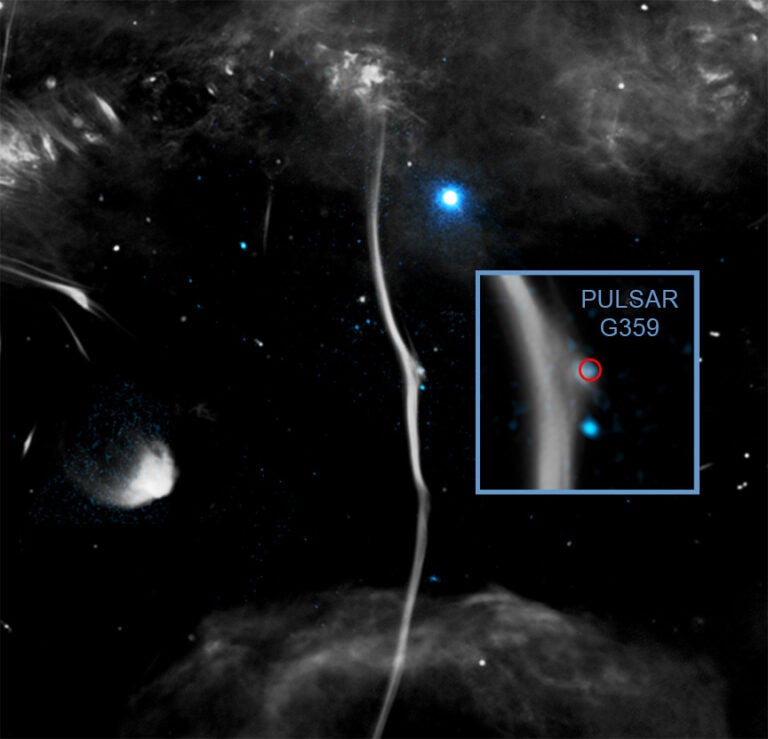

In low Earth orbit, more and more satellites are lighting up the night, especially megaconstellations like SpaceX’s Starlink.

Satellites leave bright trails through long-exposure images that overwhelm the faint targets that astronomers are trying to observe. “It’s like trying to see someone holding a candle flame in the dark while that person is also shining a flashlight in your face,” says Barentine.

The problem has quickly come to a head as the pace of commercial launches soars. “In the last three years, humankind has launched more satellites into space than we did from the beginning of the Space Age up to 2019,” says University of Illinois astrophysicist and Assistant Professor of Aerospace Engineering Siegfried Eggl. Filings with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which regulates communications satellites, indicate that up to 100,000 satellites could be launched in the foreseeable future, he notes. Without strategies to combat that, “such a large number of satellites will affect essentially all branches of astronomy, even space-based observatories such as the Hubble Space Telescope unless they are stationed far from Earth.”

A 2023 study in Nature found that 40,000 Starlink satellites will “essentially pollute every [ground-based] image with at least one streak,” he says.

But Eggl says that “with enough motivation, technical solutions can be found to almost any problem.”

Those solutions require cooperation between astronomers and satellite operators, and they are making progress. The U.S. National Science Foundation now has an agreement with SpaceX to reduce the effects of Starlink by, among other steps, lessening the satellites’ brightness and telling astronomers when and where they’ll pass overhead. But these agreements do not have the force of law.

Other companies have plans for large constellations, like AST SpaceMobile. A 2023 article in Nature found that the company’s prototype BlueWalker 3 satellite is one of the top 10 brightest night-sky objects. Here, too, astronomers are trying to work with the company to mitigate its impact on observatories.

While astronomers seek collaboration, activists are going to court. In late 2022, the advocacy group DarkSky International filed an appeal of the FCC’s decision to approve SpaceX’s plans for 7,500 Starlink satellites, arguing that it should have considered their astronomical and environmental impacts under the National Environmental Policy Act. In a press release, the organization wrote: “It is unprecedented for [DarkSky] to resort to the court system to resolve disputes. But in this case, we felt compelled to act.” A ruling is expected in mid-2024.

Global effort against light pollution

The night after our tour of Tucson, Oliver showed me the view from outside the dome of the 6.5-meter MMT Observatory on Mount Hopkins. Weather kept the stars obscured, but I could see clearly against the clouds and fog the light dome over Nogales, Mexico, 25 miles (41 km) to the south, as well as the twinkling lights of Tucson 35 miles (56 km) to the north, strung out like a glowing abacus.

Had I been alone, I would have assumed the worst. But Oliver tells me the Nogales light dome actually is shrinking.

Fernando Ávila, who heads the Dark Skies Law Office at the Astronomy Institute of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, is working with Oliver on a Smithsonian Institution project called DarkSky Net to address light pollution in Arizona and Mexico.

“In 2021, the [Mexican] federal environmental law was modified to include the terms of light pollution and intruding light,” Ávila says. “It defined the excess of artificial light at night as a pollutant.” Now Ávila is working with officials to zone areas such as astronomical observatories, natural parks, and reserves, setting maximum light levels for each. “We are trying to set these places as maximum protected areas,” he says. Ávila, too, has allies, including groups protecting sea turtles and fireflies.

Although the changes to national law have yet to trickle to the municipal level, Ávila says, most new public lighting systems have a full cutoff design that projects light downward. Although they are bright LEDs with a CCT of or over 4,000 K, the transition has been shown to shrink the light dome in the city of Ensenada. “I wouldn’t be surprised that this is what’s going in Nogales and any other city that is doing the same,” says Ávila.

And there is another factor: “a big push to promote astrotourism as viable economic activity for small communities,” says Ávila. Boosting tourism to dark-sky sites around the world could be a powerful impact multiplier, exposing people to the beauty of the night sky and Indigenous astronomical traditions while also benefiting those communities economically.

At the Namibia University of Science and Technology in Windhoek, researcher and senior lecturer Sisco Auala is also focused on this combination. “I think astrotourism can play a big role as an advocate to preserve night skies,” she says.

She adds: “I believe that Namibia has a unique opportunity to capitalize on our dark skies that could contribute to sustainable development and mitigate poverty in rural Namibia.” Ultimately, she hopes to secure the involvement of Indigenous communities and incorporate their astronomical lore into the narrative that astrotourists experience.

It’s an uphill battle, however, to “convince tourism stakeholders, including government officials, of the real potential of this niche tourism product for Namibia’s sustainable tourism development,” she says, noting that historically, the country’s tourism has been focused on wildlife. But Auala is hopeful.

At the precipice of change

Famed conservationist Aldo Leopold wrote: “One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds.” Yet wounds can be healed. At just the moment when light pollution is bleeding across the night sky, our awareness of it and our potential for partners is also increasing.

Light-pollution activism spans the globe. We know what the problem is. We have allies in the cause. And we have the tools.

The stars we’re trying to protect are our inspiration. And they’re still shining.

Responsible lighting

DarkSky’s Responsible Outdoor Lighting at Night (ROLAN) manifesto is a straightforward policy document that city councils, companies, and schools can adopt. Developed by a collaboration of dark-sky activists, policymakers, and lighting experts, its points include:

- Everyone should have the right to access darkness and quality lighting, and light needs to be used and distributed fairly without discrimination.

- Designs should start with darkness and add light only if needed to create a space where people are encouraged to dwell; this lighting should also protect a view of the stars.

- Planners should add light only to create safe spaces for people to be in and move through. These benefits should be maximized while simultaneously limiting each project’s environmental and financial costs.

Further, ROLAN cites the “Five Principles of Good Outdoor Lighting:” that it has a justifiable purpose, it isn’t brighter than necessary for that purpose, it points only where it needs to, it uses warm colors, and it’s off when it’s not needed. The key elements to a good lighting code are similar: putting light only where it’s needed; using shielded streetlights; and employing warmer, lower-temperature light in the yellow part of the spectrum instead of blue-white light.

Budding light-pollution activists can find the manifesto at www.darksky.org/news/responsible-outdoor-lighting-at-night-rolan-manifesto-for-lighting/ or search online for the lighting codes for both Tucson and Flagstaff.

Building a dark-sky coalition

In the fight against light pollution, “constituents make a difference,” says John Barentine. “What we’re missing is political will. We can reverse light pollution tomorrow. Nobody suffers when we decrease light pollution.”

The Flagstaff Dark Skies Coalition is a group focused on “celebrating, promoting, and protecting night skies,” says Chris Luginbuhl, the organization’s president. The first two verbs are key — they help build coalitions. And over time, conversation — not confrontation — can do wonders.

Change requires citizens who are, in the words of James Lowenthal, “patient, persistent, and polite.” By speaking up, meeting with officials, and engaging the public in star parties, he says, this daunting issue can become both “winnable and fun.”

Lowenthal advocates taking guidelines on responsible lighting to community centers, schools, and other institutions. Tiffany Athol adds, “You’ve got to make friends with the planners. Where are the push and pull points in your community?”

“Relations come first,” Lowenthal says. “The rest will follow.”

Those relations could be your neighbors. My friend and dark-sky activist Julie Swarstad Johnson once dreaded nights living next to a rental house’s poorly oriented and overly bright security lights. When she and her husband offered to buy dark-sky-friendly fixtures, the landlord agreed.

Even corporations can make concessions. Amy Oliver suggests talking to businesses about “fostering an ethos.” The McDonald’s in Sedona, Arizona, doesn’t light its iconic golden arches. Rather, they glow in the dark.