It is well known that winds on Venus are extremely fast and powerful. Now, European Space Agency’s (ESA) Venus Express has, for the first time, put together a 3-D picture of the venusian winds for an entire planetary hemisphere.

The most powerful atmospheric investigator ever sent to Venus, Venus Express has an advantageous orbit around the planet and a unique set of instruments. The spacecraft has the ability to peer through Venus’ thick atmospheric layers and obtain a truly global picture.

The spacecraft has continuously monitored the planet since observations began in 2006, and scientists now have enough data to start building a complete picture of the planet’s atmospheric phenomena.

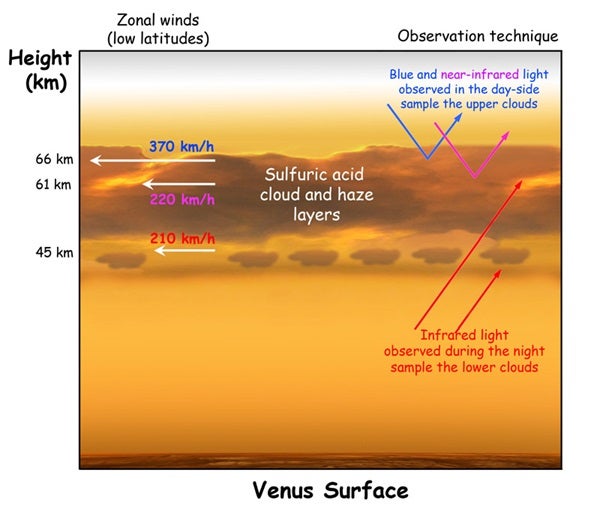

The Venus Express Visual and Infrared Thermal Imaging Spectrometer, VIRTIS, has been studying the thick blanket of clouds that surrounds Venus, gathering data on the winds. The area studied spans altitudes of 28-43.5 miles (45-70 km) above the surface and covers the entire southern hemisphere, up to the equator. It is above the southern hemisphere that Venus Express reaches its highest point in orbit (about 41,010 miles [66,000 km]), allowing the instruments to obtain a global view.

Agustin Sanchez-Lavega, from the Universidad del Pais Vasco in Bilbao, Spain, led the research on 3-D wind mapping with data from the first year of VIRTIS observations. “We focused on the clouds and their movement. Tracking them for long periods of time gives us a precise idea of the speed of the winds that make the clouds move and of the variation in the winds,” he said.

Tracking the clouds at different altitudes is possible only if the instrument is able to look through the curtain of clouds. “VIRTIS operates at different wavelengths, each of which penetrates the cloud layer to a different altitude,” added Ricardo Hueso, also from the Universidad del Pais Vasco, co-author of the results. “We studied three atmospheric layers and followed the movement of hundreds of clouds in each. This has never been done before at such large temporal and spatial scales, and with multi-wavelength coverage.”

In total, the team tracked 625 clouds at about 41 miles (66 km) altitude, 662 at around 38 miles (61 km) altitude, and 932 at about 28-29 miles (45-47 km) altitude, on the day and night sides of the planet. The individual cloud layers were imaged over several months for about 1-2 hours each time.

“We have learned that between the equator and 50-55° latitude south, the speed of the winds varies a lot, from about 230 mph at a height of 41 miles down to about 130 mph at 28-29 miles”, said Sanchez-Lavega.

“At latitudes higher than 65°, the situation changes dramatically — the huge hurricane-like vortex structure present over the poles takes over. All cloud levels are pushed on average by winds of the same speed, independently of the height, and their speed drops to almost zero at the centre of the vortex.”

Sanchez-Lavega and colleagues observed that the speed of the zonal winds (which blow parallel to the lines of latitude) strongly depends on the local time. The difference in the Sun’s heat reaching Venus in the mornings and in the evenings — called the solar tide effect — influences the atmospheric dynamics greatly, making winds blow more strongly in the evenings.

On average, the winds regain their original speeds every 5 days, but the mechanism that produces this periodicity needs further investigation. “VIRTIS is continuing its observations, and over the next few years we expect to understand more precisely how stable or variable the venusian winds at the upper and lower cloud layers are,” concluded Giuseppe Piccioni, from the Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica in Rome, co-Principal Investigator for the VIRTIS instrument.