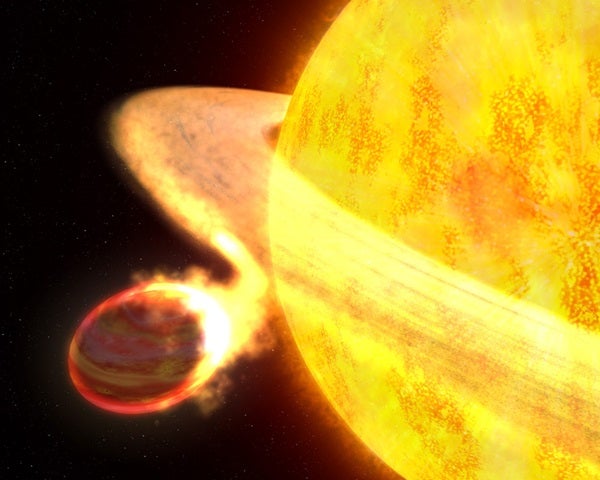

The hottest known planet in the Milky Way Galaxy may also be its shortest-lived world. The doomed planet is being eaten by its parent star according to observations made by a new instrument on NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS). The planet may have only another 10 million years left before it is completely devoured.

The planet, called WASP-12b, lies so close to its sunlike star that it is superheated to nearly 2800° Fahrenheit (1500° Celsius) and stretched into a football shape by enormous tidal forces. The atmosphere has ballooned to nearly three times Jupiter’s radius, and it is spilling material onto the star. The planet is 40 percent more massive than Jupiter.

This effect of matter exchange between two stellar objects is commonly seen in close binary star systems, but this is the first time it has been seen so clearly for a planet.

“We see a huge cloud of material around the planet which is escaping and will be captured by the star. We have identified chemical elements never before seen on planets outside our own solar system,” said Carole Haswell of The Open University in Great Britain.

A theoretical paper published last February by Shu-lin Li of the Department of Astronomy at the Peking University, Beijing, first predicted that the planet’s surface would be distorted by the star’s gravity, and that gravitational tidal forces make the interior so hot that it greatly expands the planet’s outer atmosphere. Now Hubble has confirmed this prediction.

WASP-12 is a yellow dwarf star located approximately 600 light-years away in the constellation Auriga. The United Kingdom’s Wide Area Search for Planets (WASP) discovered the exoplanet in 2008. The automated survey looks for the periodic dimming of stars from planets passing in front of them, an event called a transit. The hot planet is so close to the star it completes an orbit in 1.1 days.

The unprecedented ultraviolet (UV) sensitivity of the COS enabled measurements of the dimming of the parent star’s light as the planet passed in front of the star. These UV spectral observations showed that absorption lines from aluminum, tin, and manganese, among other elements, became more pronounced as the planet transited the star, meaning that these elements exist in the planet’s atmosphere as well as the star’s. The fact that the COS could detect these features on a planet offers strong evidence that the planet’s atmosphere is greatly extended because it is so hot.

The UV spectroscopy was also used to calculate a light curve to precisely show just how much of the star’s light is blocked out during transit. The depth of the light curve allowed the COS team to accurately calculate the planet’s radius. They found that the UV-absorbing exosphere is more extended than that of a normal planet containing 1.4 times Jupiter’s mass. It is so extended that the planet’s radius exceeds its Roche lobe, the gravitational boundary beyond which material would be lost forever from the planet’s atmosphere.