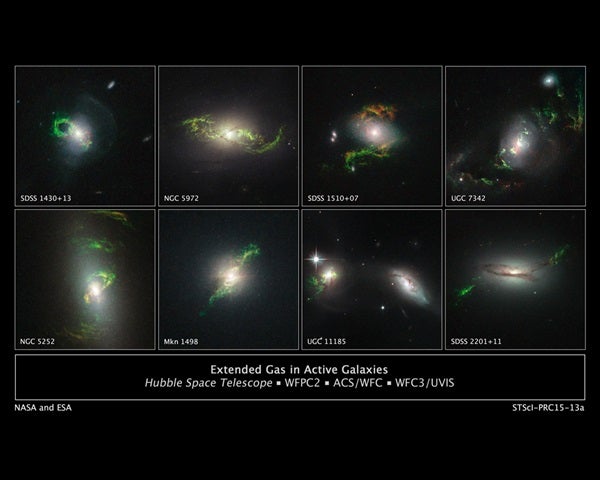

The glowing structures have looping, helical, and braided shapes. “They don’t fit a single pattern,” said Bill Keel of the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, who initiated the Hubble survey. Keel believes the features offer insights into the puzzling behavior of galaxies with energetic cores.

The ethereal wisps outside the host galaxy are believed to have been illuminated by powerful ultraviolet radiation from a supermassive black hole at the core of the host galaxy. The most active of these galaxy cores are called quasars, where infalling material is heated to a point where a brilliant searchlight shines into deep space. The beam is produced by a disk of glowing superheated gas encircling the black hole.

“However, the quasars are not bright enough now to account for what we’re seeing; this is a record of something that happened in the past,” Keel said. “The glowing filaments are telling us that the quasars were once emitting more energy or they are changing very rapidly, which they were not supposed to do.”

Keel said that one possible explanation is that pairs of co-orbiting black holes are powering the quasars, and this could change their brightness, like using the dimmer switch on a chandelier.

The quasar beam caused the once invisible filaments in deep space to glow through a process called photoionization. Oxygen atoms in the filaments absorb light from the quasar and slowly re-emit it over many thousands of years. Other elements detected in the filaments are hydrogen, helium, nitrogen, sulfur, and neon. “The heavy elements occur in modest amounts, adding to the case that the gas originated in the outskirts of the galaxies rather than being blasted out from the nucleus,” Keel said.

The green filaments are believed to be long tails of gas pulled apart like taffy under gravitational forces resulting from a merger of two galaxies. Rather than being blasted out of the quasar’s black hole, these immense structures, tens of thousands of light-years long, are slowly orbiting their host galaxy long after the merger was completed.

“We see these twisting dust lanes connecting to the gas, and there’s a mathematical model for how that material wraps around in the galaxy,” Keel said. Potentially, you can say we’re seeing it 1.5 billion years after a smaller gas-rich galaxy fell into a bigger galaxy.”

The ghostly green structures are so far outside the galaxy that they may not light up until tens of thousands of years after the quasar outburst and would likewise fade only tens of thousands of years after the quasar itself does. That’s the amount of time it would take for the quasar light to reach them.

Not coincidentally, galaxy mergers would also trigger the birth of a quasar by pouring material into the central supermassive black hole.

Because his follow-up Hubble images of Hanny’s Voorwerp were so intriguing, Keel started a deliberate hunt for more bizarre objects like it. They would share the rare and striking color signature of Hanny’s Voorwerp on the SDSS images.

Keel had 200 people volunteer specifically to look at over 15,000 galaxies hosting quasars. Each candidate had to have at least 10 views that collectively reveal weirdly colored clouds.

Keel’s team took the galaxies that looked the most promising and further studied them by dividing their light into its component colors through a process called spectroscopy. In follow-up observations from Kitt Peak National Observatory and the Lick Observatory, his team found 20 galaxies that had gas that was ionized by radiation from a quasar rather than from the energy of star formation. And the clouds extended more than 30,000 light-years outside the host galaxies.

Eight of the newly discovered clouds were more energetic than would be expected given the amount of radiation coming from the host quasar, even when observed in infrared light by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer space telescope. The host quasars were as little as one-tenth the brightness needed to provide enough energy to photoionize the gas. Keel said that presumably the brightness changes are governed by the rate at which material is falling onto the central black hole.

Keel speculated that this quasar variability might be explained if there are two massive black holes circling each other in the host galaxy’s center. This could conceivably happen after two galaxies merged. A pair of black holes whirling about each other could disrupt the steady flow of infalling gas. This would cause abrupt spikes in the accretion rate and trigger blasts of radiation.

When our Milky Way Galaxy merges with the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) in about 4 billion years, the black holes in each galaxy could wind up orbiting each other. So in the far future, our galactic system could have its own version of Hanny’s Voorwerp encircling it.