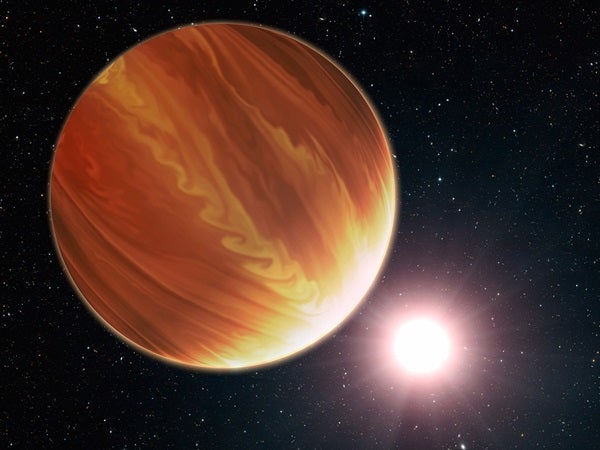

The three planets — HD 189733b, HD 209458b, and WASP-12b — are between 60 and 900 light-years away from Earth and were thought to be ideal candidates for detecting water vapor in their atmospheres because of their high temperatures where water turns into a measurable vapor.

These so-called “hot Jupiters” are so close to their stars that they have temperatures between 1500° and 4000° Fahrenheit (815° and 2200° Celsius); however, the planets were found to have only one-tenth to one one-thousandth the amount of water predicted by standard planet formation theories.

“Our water measurement in one of the planets, HD 209458b, is the highest-precision measurement of any chemical compound in a planet outside our solar system, and we can now say with much greater certainty than ever before that we’ve found water in an exoplanet,” said Nikku Madhusudhan of the Institute of Astronomy at the University of Cambridge, England. “However, the low water abundance we have found so far is quite astonishing.”

Madhusudhan said that this finding presents a major challenge to exoplanet theory. “It basically opens a whole can of worms in planet formation. We expected all these planets to have lots of water in them. We have to revisit planet formation and migration models of giant planets, especially ‘hot Jupiters,’ and investigate how they’re formed.”

He emphasizes that these results may have major implications in the search for water in potentially habitable Earth-sized exoplanets. Instruments on future space telescopes may need to be designed with a higher sensitivity if target planets are drier than predicted. “We should be prepared for much lower water abundances than predicted when looking at super-Earths (rocky planets that are several times the mass of Earth),” Madhusudhan said.

Using near-infrared spectra of the planets observed with Hubble, Madhusudhan and his collaborators estimated the amount of water vapor in each of the planetary atmospheres that explains the data. The planets were selected because they orbit relatively bright stars that provide enough radiation for an infrared-light spectrum to be taken. Absorption features from the water vapor in the planet’s atmosphere are detected because they are superimposed on the small amount of starlight that glances through the planet’s atmosphere.

Detecting water is almost impossible for transiting planets from the ground because Earth’s atmosphere has a lot of water in it, which contaminates the observation. “We really need the Hubble Space Telescope to make such observations,” said Nicolas Crouzet of the Dunlap Institute at the University of Toronto.

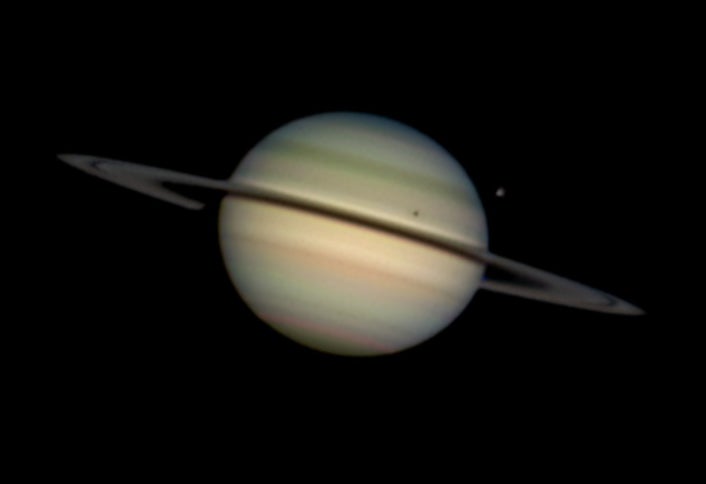

The currently accepted theory on how giant planets in our solar system formed, known as core accretion, states that a planet forms around the young star in a protoplanetary disk made primarily of hydrogen, helium, and particles of ices and dust composed of other chemical elements. The dust particles stick to each other, eventually forming larger and larger grains. The gravitational forces of the disk draw in these grains and larger particles until a solid core forms. This then leads to runaway accretion of both solids and gas to eventually form a giant planet.

This theory predicts that the proportions of the different elements in the planet are enhanced relative to those in its star, especially oxygen, which is supposed to be the most enhanced. Once the giant planet forms, its atmospheric oxygen is expected to be largely encompassed within water molecules. The low levels of water vapor found by this research raise a number of questions about the chemical ingredients that lead to planet formation.

“There are so many things we still don’t know about exoplanets, so this opens up a new chapter in understanding how planets and solar systems form,” said Drake Deming of the University of Maryland. “The problem is that we are assuming the water to be as abundant as in our solar system. What our study has shown is that water features could be a lot weaker than our expectations.”