If the era when the first galaxies formed can be called the opening act in the universe’s history, then the Hubble Space Telescope has given scientists a front-row seat. Astronomers gathered at the Space Telescope Institute in Baltimore September 23 to review their initial analysis of the spectacular Hubble Ultra Deep Field (HUDF) photo released 6 months ago. Their preliminary view was that some of the structures contained in the image were a sampling of the earliest star-forming galaxies ever seen. But analysis continues, and it contains both the seeds of consensus as well as controversy about what scientists are seeing in the depths of space. The faint images in the HUDF were generated by the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) and the deep-penetrating capability of the Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS).

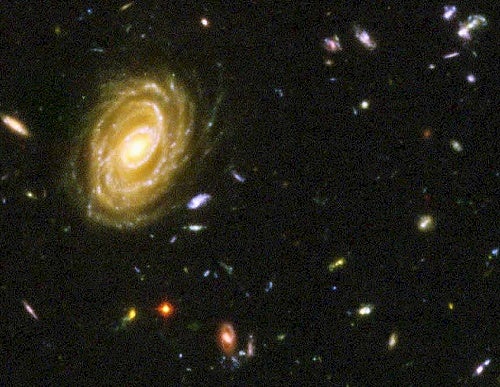

The HUDF image sees sources about 95 percent of the way back to the Big Bang. The objects in the image that were targeted for study now are believed to be some of the earliest galaxies under formation. “What we see here is a complex array of objects; some 10,000 galaxies are visible,” said Steve Beckwith, the institute’s director. “They are faint, fuzzy things at the edge of the universe,” he added. “These things are just train wrecks.”

While consensus exists about what the structures are — galaxies in their earliest formative stages — there is controversy about what they signify. Astronomers have sought to affirm that the universe contained a reionization epoch, a period when hydrogen atoms absorbed sufficient energy from ultraviolet light that they became stripped of their electrons. The effect was to make the universe transparent to light, following the earlier era when the ultra-hot universe was an ionized haze of hydrogen nuclei and free-moving electrons. As the universe cooled, the electrons were captured by the hydrogen nuclei only to be lost again when the first stars ignited.

That period of ionization is thought to have ended about 500 million to a billion years after the Big Bang. Galaxies so distant have been nearly impossible to locate with existing telescopes and spacecraft. Within the HUDF image, such reionized structures are believed to be visible. But not all agree. “Like most cutting-edge science, there is controversy about the results,” Beckwith said.

“The HUDF illustrates the unique role of deep Hubble data and the merits of publicly available data sets,” said Lick Observatory’s Richard Ellis. All agree the Hubble’s optical and near-infrared cameras have captured an abundance of early, young galaxies when the universe was 600-900 million years old. “This is an observational first,” Ellis said. The question is, “Has Hubble found the first sources switching on after the ‘Dark Ages,’ during which there was only pure hydrogen and helium?” And are these sources sufficient to be responsible for “lifting the curtain” and ending the Dark Ages?

Part of the reason doubt exists is the small slice of sky the HUDF imaged and the limited number and faintness of the early galaxies seen. “The limits to which these sources can be reliably detected will require further study and additional data,” said Andrew Bunker of the University of Cambridge. “We will need to know more about these individual sources,” predicted the institute’s Massimo Stiavelli. “How hot are they?” and “What is their composition?”

To answer the riddle of whether or not the reionization era is visible requires detecting even earlier galaxies. “Are there yet earlier sources?” asked Ellis. The newly completed infrared Wide-Field Camera 3 will be key to imaging these earlier structures — if they can be detected. While Hubble was able to see back to the universe’s cosmic dawn, it will be the James Webb Space Telescope that offers the promise of detailed physical studies of such earlier sources. “What ionized the cosmic hydrogen?” asked Robert Kirshner of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. “The HUDF allows us to move the discussion from theory to observation.”