Lying about 50 million light-years away, M60-UCD1 is a tiny galaxy with a diameter of 300 light-years — just 1/500 the diameter of the Milky Way. Despite its size, it is pretty crowded, containing some 140 million stars. While this is characteristic of an ultra-compact dwarf galaxy (UCD) like M60-UCD1, this particular UCD happens to be the densest ever seen.

Despite their huge numbers of stars, UCDs always seem to be heavier than they should be. Now, an international team of astronomers has made a new discovery that may explain why: At the heart of M60-UCD1 lurks a supermassive black hole with the mass of 20 million Suns.

“We’ve known for some time that many UCDs are a bit overweight. They just appear to be too heavy for the luminosity of their stars,” said Steffen Mieske of the European Southern Observatory in Chile. “We had already published a study that suggested this additional weight could come from the presence of supermassive black holes, but it was only a theory. Now, by studying the movement of the stars within M60-UCD1, we have detected the effects of such a black hole at its center. This is a very exciting result, and we want to know how many more UCDs may harbor such extremely massive objects.”

The supermassive black hole at the center of M60-UCD1 makes up a huge 15 percent of the galaxy’s total mass and weighs five times the black hole at the center of the Milky Way. “That is pretty amazing given that the Milky Way is 500 times larger and more than 1,000 times heavier than M60-UCD1,” said Anil Seth of the University of Utah. “In fact, even though the black hole at the center of our Milky Way Galaxy has the mass of 4 million Suns, it is still less than 0.01 percent of the Milky Way’s total mass, which makes you realize how significant M60-UCD1’s black hole really is.”

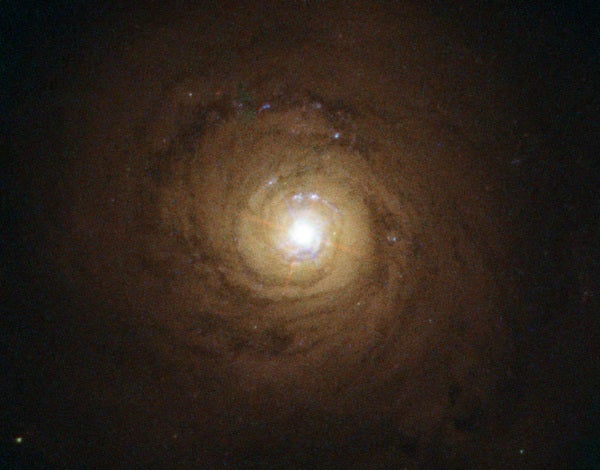

The team discovered the supermassive black hole by observing M60-UCD1 with both the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and the Gemini North 8-meter optical and infrared telescope on Hawaii’s Mauna Kea. The sharp Hubble images provided information about the galaxy’s diameter and stellar density, while Gemini was used to measure the movement of stars in the galaxy as they were affected by the black hole’s gravitational pull. These data were then used to calculate the mass of the unseen black hole.

The finding implies that there may be a substantial population of previously unnoticed black holes. In fact, the astronomers predict there may be as many as double the known number of black holes in the local universe.

Additionally, the results could affect theories of how such UCDs form. “This finding suggests that dwarf galaxies may actually be the stripped remnants of larger galaxies that were torn apart during collisions with other galaxies, rather than small islands of stars born in isolation,” said Seth. “We don’t know of any other way you could make a black hole so big in an object this small.”

One explanation is that M60-UCD1 was once a large galaxy containing 10 billion stars and a supermassive black hole to match. “This galaxy may have passed too close to the center of its much larger neighboring galaxy, Messier 60,” said Remco van den Bosch of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. “In that process, the outer part of the galaxy would have been torn away to become part of Messier 60, leaving behind only the small and compact galaxy we see today.”

The team believes that M60-UDC1 may one day merge with Messier 60 to form a single galaxy. Messier 60 also has its own monster black hole an amazing 4.5 billion times the size of our Sun and more than 1,000 times bigger than the black hole in our Milky Way. A merger between the two galaxies would also cause the black holes to merge, creating an even more monstrous black hole.