Hubble observations show the exoplanet, called WASP-43b, is no place to call home. It is a world of extremes, where seething winds howl at the speed of sound from a 3,000° Fahrenheit (1,650° Celsius) “day” side, hot enough to melt steel, to a pitch-black “night” side with plunging temperatures below 1,000° F (500° C).

Astronomers have mapped the temperatures at different layers of the planet’s atmosphere and traced the amount and distribution of water vapor. The findings have ramifications for the understanding of atmospheric dynamics and how giant planets like Jupiter are formed.

“These measurements have opened the door for new kinds of ways to compare the properties of different types of planets,” said team leader Jacob Bean of the University of Chicago.

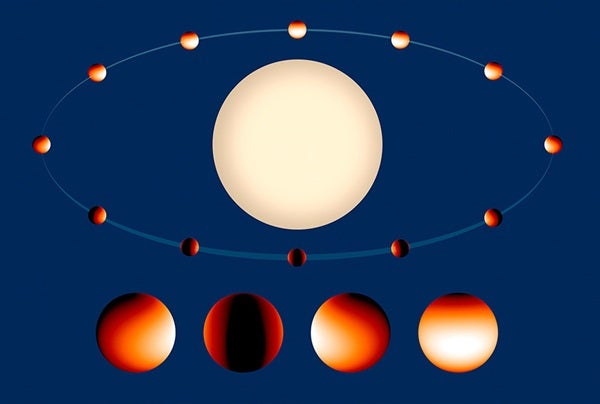

First discovered in 2011, WASP-43b is located 260 light-years away. The planet is too distant to be photographed, but because its orbit is observed edge-on to Earth, astronomers detected it by observing regular dips in the light of its parent star as the planet passes in front of it.

“Our observations are the first of their kind in terms of providing a 2-D map on the longitude and altitude of the planet’s thermal structure that can be used to constrain atmospheric circulation and dynamical models for hot exoplanets,” said Kevin Stevenson of the University of Chicago.

As a hot ball of predominantly hydrogen gas, there are no surface features on the planet such as oceans or continents that can be used to track its rotation. Only the severe temperature difference between the day and night sides can be used by a remote observer to mark the passage of a day on this world.

The planet is about the same size as Jupiter but is nearly twice as dense. The planet is so close to its orange dwarf host star that it completes an orbit in just 19 hours. The planet also is gravitationally locked so that it keeps one hemisphere facing the star, just as our Moon keeps one face toward Earth.

This was the first time astronomers were able to observe three complete rotations of any planet, which occurred during a span of four days. Scientists combined two previous methods of analyzing exoplanets in an unprecedented technique to study the atmosphere of WASP-43b. They used spectroscopy, dividing the planet’s light into its component colors, to determine the amount of water and the temperatures of the atmosphere. By observing the planet’s rotation, the astronomers also were able to precisely measure how the water is distributed at different longitudes.

Because there is no planet with these tortured conditions in our solar system, characterizing the atmosphere of such a bizarre world provides a unique laboratory for better understanding planet formation and planetary physics.

“The planet is so hot that all the water in its atmosphere is vaporized rather than condensed into icy clouds like on Jupiter,” said Laura Kreidberg of the University of Chicago.

The amount of water in the giant planets of our solar system is poorly known because water that has precipitated out of the upper atmospheres of cool gas giant planets like Jupiter is locked away as ice. But at so-called “hot Jupiters,” gas giants that have high surface temperatures because they orbit very close to their stars, water is in a vapor that can be readily traced.

“Water is thought to play an important role in the formation of giant planets since comet-like bodies bombard young planets, delivering most of the water and other molecules that we can observe,” said Jonathan Fortney from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

In order to understand how giant planets form, astronomers want to know how enriched they are in different elements. The team found that WASP-43b has about the same amount of water as we would expect for an object with the same chemical composition as our Sun, shedding light on the fundamentals about how the planet formed. The team next aims to make water-abundance measurements for different planets.