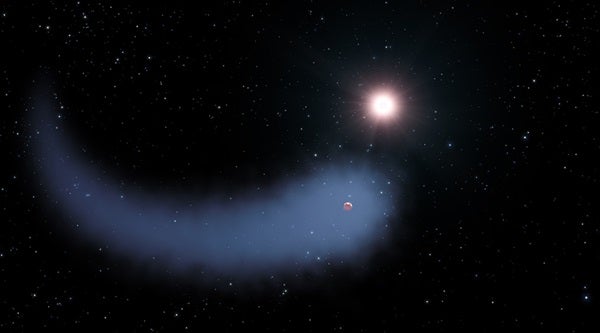

A phenomenon this large has never before been seen around any exoplanet. Given this planet’s small size, it may offer clues to how hot super-Earths — massive, rocky, hot versions of Earth — are born around other stars through the evaporation of their outer layers of hydrogen.

“This cloud is very spectacular, though the evaporation rate does not threaten the planet right now,” said David Ehrenreich of the Observatory of the University of Geneva in Switzerland. “But we know that in the past, the star, which is a faint red dwarf, was more active. This means that the planet evaporated faster during its first billion years of existence. Overall, we estimate that it may have lost up to 10 percent of its atmosphere.”

The planet, named GJ 436b, is considered to be a “warm Neptune” because of its size, and it is much closer to its star than Neptune is to our Sun. Although it is in no danger of having its atmosphere completely evaporated and being stripped down to a rocky core, this planet could explain the existence of so-called hot super-Earths that are close to their stars.

The Convection Rotation and Planetary Transits (CoRoT) spacecraft — led by the French Space Agency (CNES) — in collaboration with the European Space Agency (ESA), several other international partners, and NASA’s Kepler space telescope, discovered these hot, rocky worlds. Hot super-Earths could be the remnants of more massive planets that completely lost their thick gaseous atmospheres to the same type of evaporation.

Because Earth’s atmosphere blocks most ultraviolet light, astronomers needed a space telescope with Hubble’s ultraviolet capability and exquisite precision to find “The Behemoth.”

“You would have to have Hubble’s eyes,” said Ehrenreich. “You would not see it in visible wavelengths. But when you turn the ultraviolet eye of Hubble onto the system, it’s really kind of a transformation because the planet turns into a monstrous thing.”

Ehrenreich and his team think that such a huge cloud of gas can exist around this planet because the cloud is not rapidly heated and swept away by the radiation pressure from the relatively cool red dwarf star. This allows the cloud to stick around for a longer time.

Evaporation such as this may have happened in the earlier stages of our solar system when Earth had a hydrogen-rich atmosphere that dissipated over 100 million to 500 million years. If so, Earth may previously have sported a comet-like tail. It’s also possible it could happen to Earth’s atmosphere at the end of our planet’s life when the Sun swells up to become a red giant and boils off our remaining atmosphere before engulfing our planet completely.

GJ 436b resides close to its star — less than 3 million miles (5 million kilometers) — and whips around it in just 2.6 Earth days. In comparison, Earth is 93 million miles (150 million km) from our Sun and orbits it every 365.24 days. This exoplanet is at least 6 billion years old and may even be twice that age. It has a mass of around 23 Earths. At just 30 light-years from Earth, it’s one of the closest known extrasolar planets.

Finding “The Behemoth” could be a game-changer for characterizing atmospheres of the whole population of Neptune-sized planets and super-Earths in ultraviolet observations. In the coming years, Ehrenreich expects that astronomers will find thousands of this kind of planet.

The ultraviolet technique used in this study also may spot the signature of oceans evaporating on smaller, more Earth-like planets. It will be extremely challenging for astronomers to directly see water vapor on those worlds because it’s too low in the atmosphere and shielded from telescopes. However, when water molecules are broken by the stellar radiation into hydrogen and oxygen, the relatively light hydrogen atoms can escape the planet. If scientists could spot this hydrogen evaporating from a planet that is a bit more temperate and little less massive than GJ 436b, that is a good sign of an ocean on the surface.