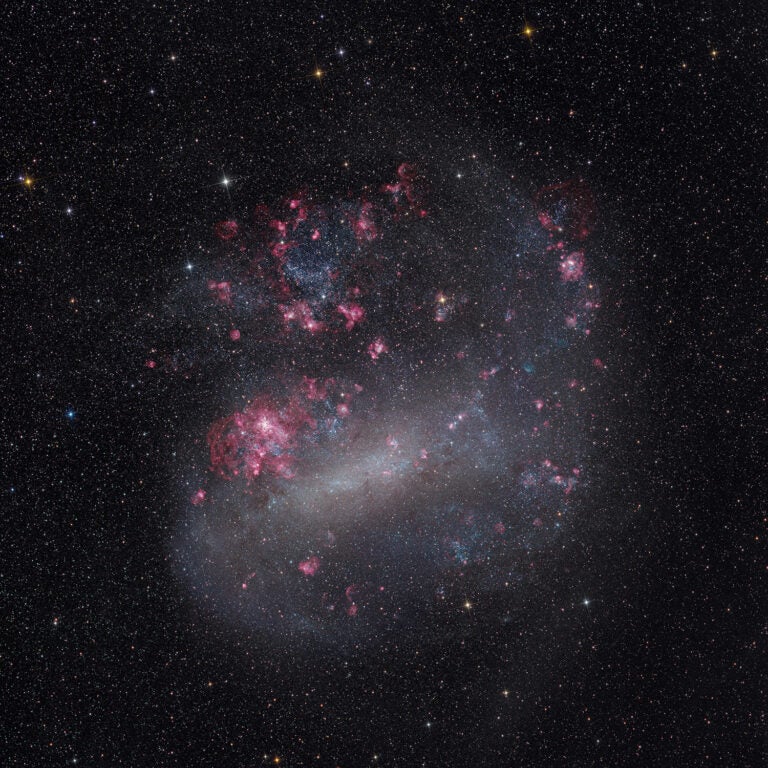

A team of astronomers using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope’s Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) has conducted a large survey to investigate the relationship between galaxies that have undergone mergers and the activity of the supermassive black holes at their cores.

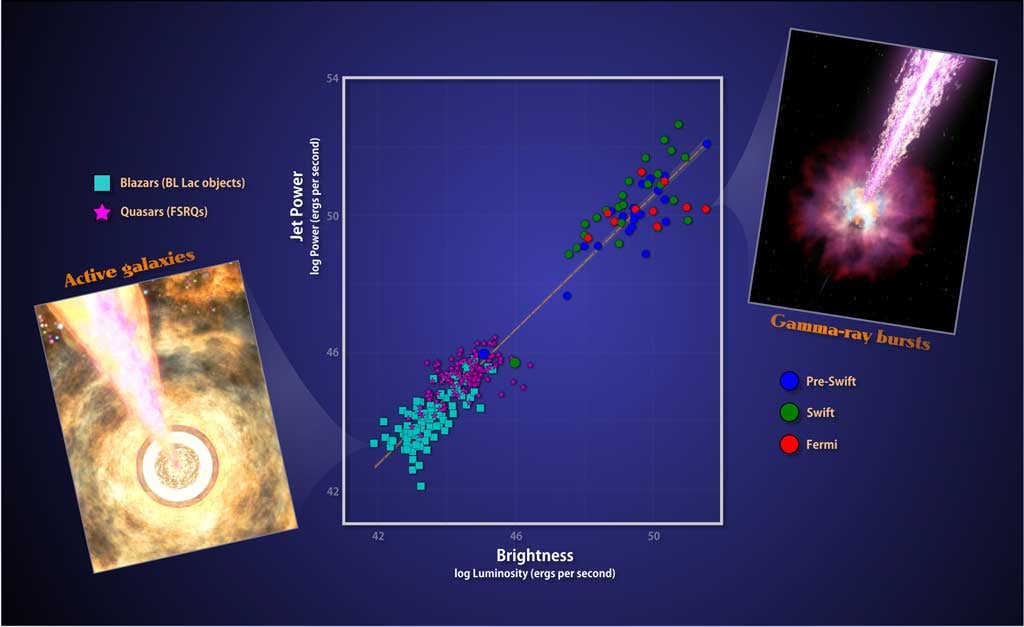

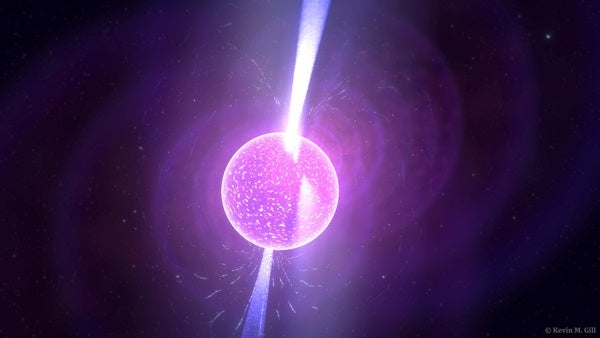

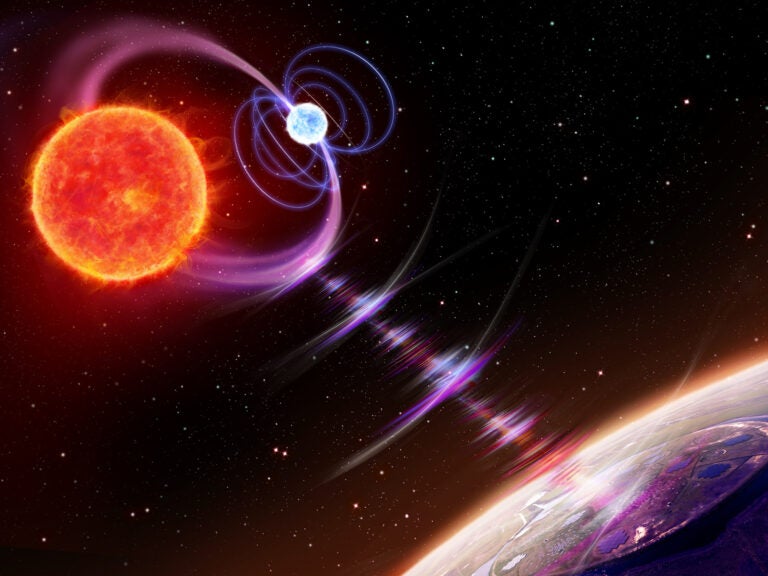

The team studied a large selection of galaxies with extremely luminous centers — known as active galactic nuclei (AGNs) — thought to be the result of large quantities of heated matter circling around and being consumed by a supermassive black hole. While most galaxies are thought to host a supermassive black hole, only a small percentage of them are this luminous, and fewer still go one step further and form what are known as relativistic jets. The two high-speed jets of plasma move almost with the speed of light and stream out in opposite directions at right angles to the disk of matter surrounding the black hole, extending thousands of light-years into space. The hot material within the jets is also the origin of radio waves.

It is these jets that Marco Chiaberge from the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, and his team hoped to confirm were the result of galactic mergers.

The team inspected five categories of galaxies for visible signs of recent or ongoing mergers — two types of galaxies with jets, two types of galaxies that had luminous cores but no jets, and a set of regular inactive galaxies.

“The galaxies that host these relativistic jets give out large amounts of radiation at radio wavelengths,” said Chiaberge. “By using Hubble’s WFC3 camera, we found that almost all of the galaxies with large amounts of radio emission, implying the presence of jets, were associated with mergers. However, it was not only the galaxies containing jets that showed evidence of mergers!”

Although it is now clear that a galactic merger is almost certainly necessary for a galaxy to host a supermassive black hole with relativistic jets, the team deduces that there must be additional conditions which need to be met. They speculate that the collision of one galaxy with another produces a supermassive black hole with jets when the central black hole is spinning faster — possibly as a result of meeting another black hole of a similar mass — as the excess energy extracted from the black hole’s rotation would power the jets.

“There are two ways in which mergers are likely to affect the central black hole. The first would be an increase in the amount of gas being driven towards the galaxy’s center, adding mass to both the black hole and the disk of matter around it,” said Colin Norman. “But this process should affect black holes in all merging galaxies, and yet not all merging galaxies with black holes end up with jets, so it is not enough to explain how these jets come about. The other possibility is that a merger between two massive galaxies causes two black holes of a similar mass to also merge. It could be that a particular breed of merger between two black holes produces a single spinning supermassive black hole, accounting for the production of jets.”

Future observations using both Hubble and ESO’s Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) are needed to expand the survey set even further and continue to shed light on these complex and powerful processes.