Studying globular clusters is critical to understanding the early intense star-forming episodes that marked galaxy formation. The Hubble observations also confirm that these compact stellar groupings can be used as reliable tracers of the amount of dark matter locked away in immense galaxy clusters.

Globular clusters, dense bunches of hundreds of thousands of stars, are the homesteaders of galaxies, containing some of the oldest surviving stars in the universe. Almost 95 percent of globular cluster formation occurred within the first 1 billion or 2 billion years after our universe was born in the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago.

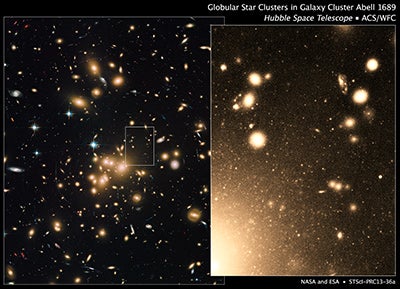

A team of astronomers, led by John Blakeslee of the NRC Herzberg Astrophysics Program at the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory in Victoria, British Columbia, used Hubble’s sensitivity and sharpness to discover a bounty of these stellar fossils — roughly twice as large as any other population found in previous globular cluster surveys. The Hubble observations also win the distance record for the farthest such systems ever studied, at 2.25 billion light-years away.

The research team found that the globular clusters are intimately intertwined with dark matter. “In our study of Abell 1689, we show how the relationship between globular clusters and dark matter depends on the distance from the galaxy cluster’s center,” explained team member Karla Alamo-Martinez of the Center for Radio Astronomy and Astrophysics of the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Morelia. “In other words, if you know how many globular clusters are within a certain distance, we can give you an estimate of the amount of dark matter.”

Although dark matter is invisible, it is the underlying gravitational scaffolding upon which stars and galaxies are built. Understanding dark matter can yield clues about how large structures such as galaxies and galaxy clusters were assembled billions of years ago.

The Hubble study shows that most of the globular clusters in Abell 1689 formed near the center of the galaxy cluster, which contains a deep well of dark matter. Their number decreases the farther Hubble looked from the core, corresponding with a comparable drop in the amount of dark matter.

“The globular clusters are fossils of the earliest star formation in Abell 1689, and our work shows they were very efficient in forming in the denser regions of dark matter near the center of the galaxy cluster,” Blakeslee said. “Our findings are consistent with studies of globular clusters in other galaxy clusters but extend our knowledge to regions of higher dark matter density.”

The astronomers used Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys to peer deep inside the heart of Abell 1689, detecting the visible-light glow of 10,000 globular clusters, some as dim as 29th magnitude. Based on that number, Blakeslee’s team estimated that more than 160,000 globular clusters are huddled within a diameter of 2.4 million light-years. “Even though we are looking deep into the cluster, we’re only seeing the brightest globular clusters, and only near the center of Abell 1689 where Hubble was pointed,” he said.

The brightness of most of the globular clusters is estimated to be 31st magnitude. This is out of reach for Hubble, but not for NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, an infrared observatory scheduled to launch later this decade. By going fainter, Webb should be able to see many more of the globular clusters.

Blakeslee’s quest to use Hubble to conduct a globular cluster census in Abell 1689 began 10 years ago after astronauts added the Advanced Camera for Surveys to Hubble’s arsenal of science instruments. While analyzing some gravitational lensing data of Abell 1689 obtained with the newly installed camera, Blakeslee spotted dots of light peppered throughout the images. The dots turned out to be the brightest members of a teeming population of globular clusters.