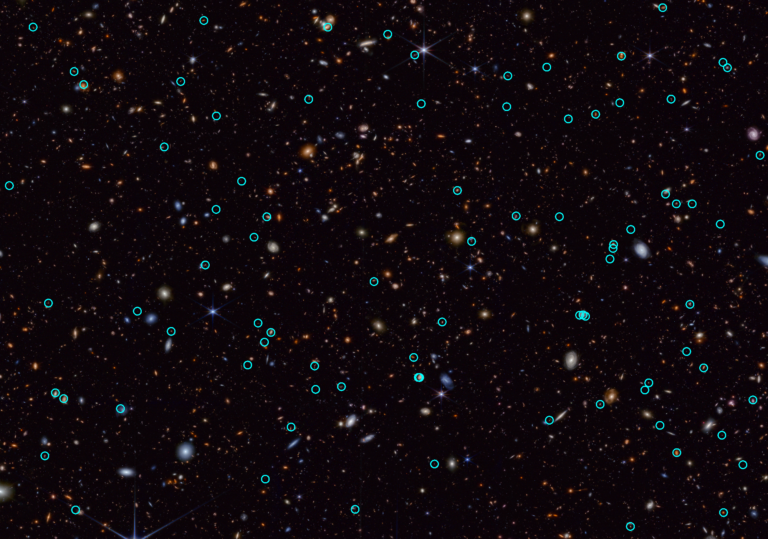

The project, known as the Kilo-Degree Survey (KiDS), uses imaging from the VST and its huge camera, OmegaCAM, to analyze images of over 2 million galaxies. The KiDS team studied the distortion of light emitted from these galaxies, which bends as it passes massive clumps of dark matter during its journey to Earth. From the gravitational lensing effect, these groups turn out to contain around 30 times more dark than visible matter.

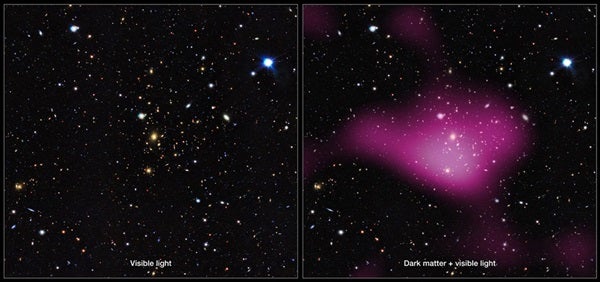

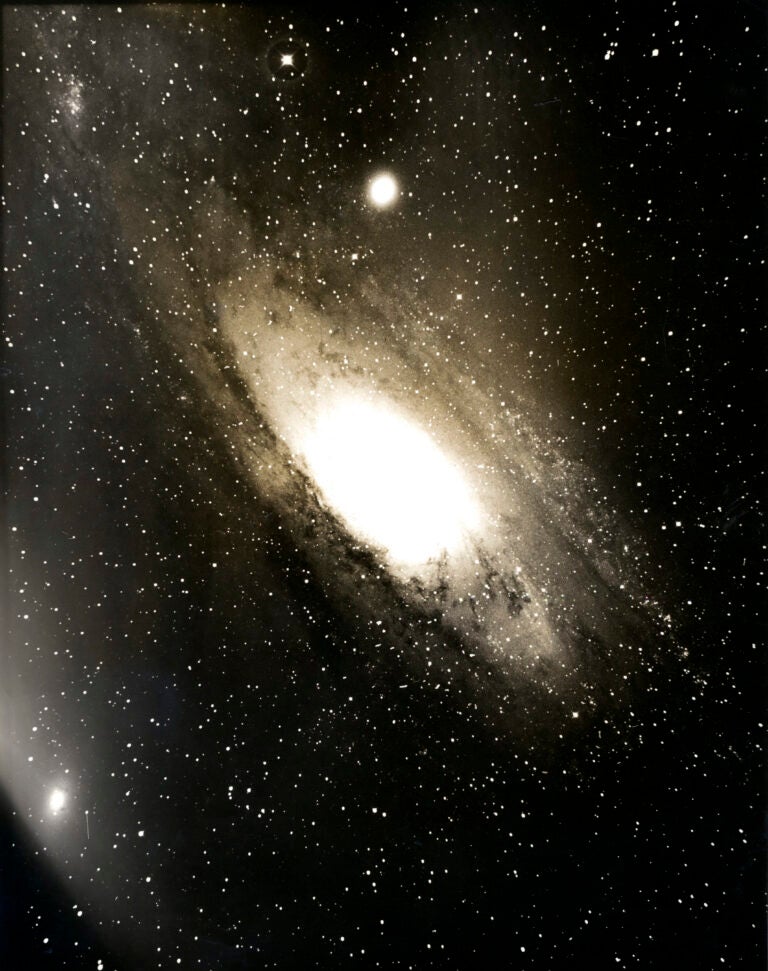

Left, a group of galaxies mapped by KiDS. Right, the same area of sky, but with the invisible dark matter rendered in pink.

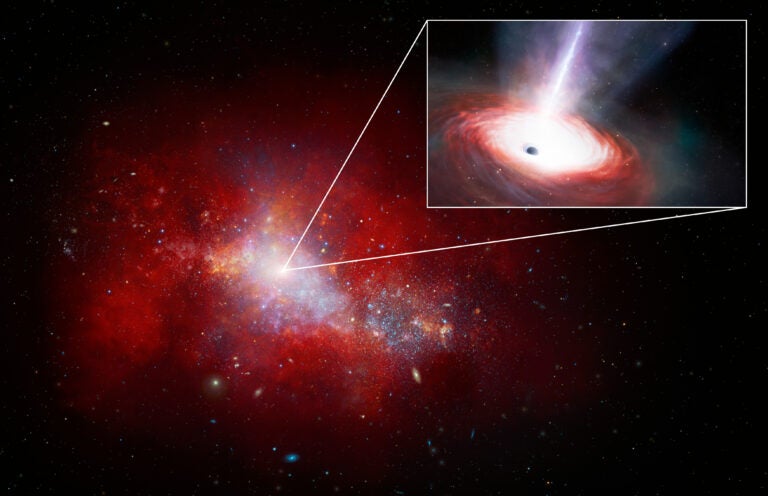

Around 85 percent of the matter in the universe is dark and of a type not understood by physicists. Although it doesn’t shine or absorb light, astronomers can detect this dark matter through its effect on stars and galaxies, specifically from its gravitational pull. A major project using ESO’s powerful survey telescopes is now showing more clearly than ever before the relationships between this mysterious dark matter and the shining galaxies that we can observe directly.

The project uses imaging from the VLT Survey Telescope and its huge camera, OmegaCAM. Sited at ESO’s Paranal Observatory in Chile, this telescope is dedicated to surveying the night sky in visible light, and it is complemented by the infrared survey telescope VISTA. One of the major goals of the VST is to map out dark matter and to use these maps to understand the mysterious dark energy that is causing our universe’s expansion to accelerate.

The best way to work out where the dark matter lies is through gravitational lensing — the distortion of the universe’s fabric by gravity, which deflects the light coming from distant galaxies far beyond the dark matter. By studying this effect, it is possible to map out the places where gravity is strongest, and hence where the matter, including dark matter, resides.

As part of the first cache of papers, the international KiDS team of researchers, led by Koen Kuijken at the Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands, has used this approach to analyze images of over 2 million galaxies, typically 5.5 billion light-years away. They studied the distortion of light emitted from these galaxies, which bends as it passes massive clumps of dark matter during its journey to Earth.

The first results come from only 7 percent of the final survey area and concentrate on mapping the distribution of dark matter in groups of galaxies. Most galaxies live in groups — including our Milky Way, which is part of the Local Group — and understanding how much dark matter they contain is a key test of the whole theory of how galaxies form in the cosmic web. From the gravitational lensing effect, these groups turn out to contain around 30 times more dark than visible matter.

“Interestingly, the brightest galaxy nearly always sits in the middle of the dark matter clump,” said Massimo Viola from Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands.

“This prediction of galaxy formation theory in which galaxies continue to be sucked into groups and pile up in the center has never been demonstrated so clearly before by observations,” said Koen Kuijken.

The findings are just the start of a major program to exploit the immense datasets coming from the survey telescopes, and the data are now being made available to scientists worldwide through the ESO archive.

The KiDS survey will help to further expand our understanding of dark matter. Being able to explain dark matter and its effects would represent a major breakthrough in physics.