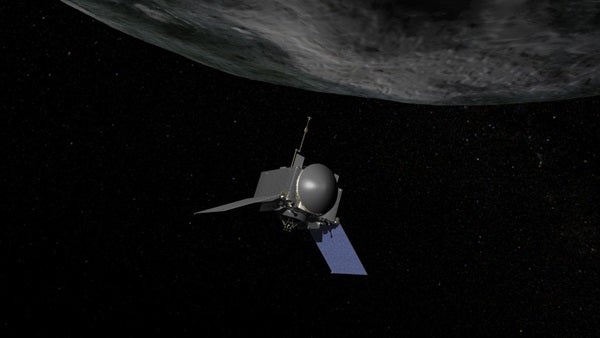

On September 8, 2016, NASA deployed its OSIRIS-REx spacecraft on an extraterrestrial mission: to track down an asteroid hurtling towards earth.

The asteroid, nicknamed Bennu, isn’t projected to hit until the 22nd century, and even then it has a less-than-one-percent chance of doing so. But scientists are taking no chances: the spacecraft will travel for two years to reach the surface of the asteroid, collect a sample of surface material, and return to Earth by 2023. Scientists plan to analyze the trajectory of Bennu and calculate the risk it poses to the planet—which, at an impact size of 500 meters across, could end up making a crater on Earth’s surface about 3 miles wide. “That would really be bad news for a few congressional districts,” said Richard Binzel, professor of Planetary Sciences at MIT and a co-investigator on the OSIRIS-REx mission, at a recent talk on the mission hosted by the Kavli Foundation.

But researchers also have a second, even more intriguing purpose: to analyze the carbon-rich asteroid to help piece together how asteroids may have contributed to the development of life on earth. At a NASA briefing on August 17, Gordon Johnston, Program Executive for OSIRIS-REx, noted that the asteroid Bennu “can answer some fundamental questions about the origins of our solar system and our planet.” That’s because Bennu is a carbonaceous regolith—a primitive asteroid that has undergone very little change in the past 4.5 billion years.

The spacecraft will reach Bennu in August 2018 and spend two years scanning and taking pictures in order to create a three-dimensional map of Bennu, which will help scientists determine where to collect a sample from. OSIRIS-REx won’t land—instead, it will then extend its 11-foot-long robot arm, TAGSAM (Touch-and-Go-Sample-Acquisition-Mechanism) to collect about 60 grams of material. TAGSAM will give the asteroid a “gentle high-five“, making contact with the surface for only about 5 seconds in order to collect its sample. OSIRIS-REx will then journey back to Earth and drop off the sample at a Utah testing range in 2023, where it will be brought to the Johnson Space Center for further study.

What can this material tell us about the origins of life? According to NASA researchers, quite a lot. That’s because researchers expect to find a pristine, primitive environment on Bennu that includes organic molecules leftover from the formation of the solar system. The environment is pristine because it has escaped significant heat and processing, and so may more closely mimic the environment of the early solar system.

And this environment has many secrets to reveal. For instance, researchers hope to examine the concentrations of amino acids in the asteroid and determine whether Bennu contains a higher concentration of those 20 amino acids used by life forms on earth. The “handedness,” or chirality, of such amino acids is also important. Life on earth developed using only “left-handed” amino acids, though scientists are not sure why. Determining Bennu’s makeup of right-handed and left-handed amino acids may provide researchers with some insights into when Earth’s preference for left-handed amino acids occurred.

Even more important, Professor Binzel noted at the Kavli talk, was that the sample researchers would obtain would come from a known environment. Scientists would understand where it came from, and how representative it was. “These meteorites are fantastic, but they don’t come with return addresses,” said Professor Binzel, holding up fragments of the Tagish Lake meteorite, which struck earth in January 2000.

And take this for a coincidence: about 4.1 billion to 3.8 billion years ago, asteroids peppered the earth during a period scientists call the”Late Heavy Bombardment“—which also happens to be the approximate time of the origin of life. Researchers hypothesize that these asteroids may have delivered organic material and water to the early Earth. Asteroids may thus represent a “stellar nursery” from which life on earth developed.

Bennu is still on NASA’s list of Potentially Hazardous Asteroids, and scientists say there’s still a small chance (about 1 in 2000) that Bennu could hit Earth late in the 22nd century. As Binzel put it, such an impact would not be the end of civilization or of life, but “just a really bad day.”

But for scientists, it’s all about the opportunities Bennu affords, and always has been. Dr. Dante Lauretta, OSIRIS-REx Principal Investigator and Professor of Planetary Science and Cosmochemistry at the University of Arizona, told me that the sample return was always the primary science driving the OSIRIS-REx mission. Determining the molecular makeup of the asteroid—and potentially finding the building blocks of amino acids, nucleic acids, sugars, and phosphates—will help researchers pinpoint the processes that led to the formation of life. Specifically, did the major steps in the evolution of essential molecules occur in space? Or might the asteroids have delivered essential building blocks that underwent major developments on earth? Bennu, far beyond any previous mission, will help scientists answer this question. Added Dr. Lauretta, “I’m not going to expect anything other than to be surprised by the asteroid.”

At the news briefing in August, NASA scientists revealed one final, intriguing part of their plan: while 4% of the sample is going to Canada, and half a percent of the sample is going to Japan (thanks to their contributions to the effort), a whopping 75% of the sample is being set aside and will not be touched at all. This is because researchers are storing it for future use, for the questions scientists haven’t even figured out to ask yet, using instruments that they haven’t even developed yet. And that legacy of Bennu may last far beyond its marginal threat.