Matt Quandt

Assistant editor

(w) 262.796.8776 x.419

(cell) 414.719.0116

mquandt@astronomy.com

December 22, 2004

In this release:

Let the mission begin – Titan’s hazy, dense atmosphere – Titan’s wet surface? – Descent details – Fast facts about the mission – Links to public-domain images of Cassini and Huygens – Astronomy magazine’s extensive Cassini coverage

Let the mission begin

WAUKESHA, WI – While children look to the sky Christmas Eve, hoping to catch a glimpse of Santa Claus, planetary scientists will be gazing at computer screens to monitor celestial goings-on. But these grown-ups won’t be concerned with the progress of a red-suited man in a sleigh. Instead, they will be following the progress of a golden-colored spacecraft starting the final leg of its 7-year, 2.25-billion-mile (3.62 billion kilometer) journey.

If all goes according to schedule, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft will release the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe the evening of December 24. Cassini has been orbiting Saturn for the past 6 months, sending back marvelous photographs and other data about the planet, its rings, and its family of moons. The Huygens probe has been riding piggyback all along, waiting for its time to come. Its sole purpose is to execute a 2.5-hour dive through the thick, hazy atmosphere of Saturn’s giant moon, Titan. If the mission is a success, scientists will get their first close look at the atmosphere and surface of this enigmatic moon.

Titan’s hazy, dense atmosphere

Titan’s atmosphere consists mostly of nitrogen – just like Earth’s – with small amounts of methane, ethane, acetylene, and other hydrocarbons mixed in. The atmosphere is 10 times thicker and exerts a surface pressure 50-percent greater than Earth’s. At Titan’s surface temperature – about -290° Fahrenheit (-179° Celsius) – methane should condense out of the atmosphere and “rain” down. Some scientists think lakes of liquid hydrocarbons might exist on Titan.

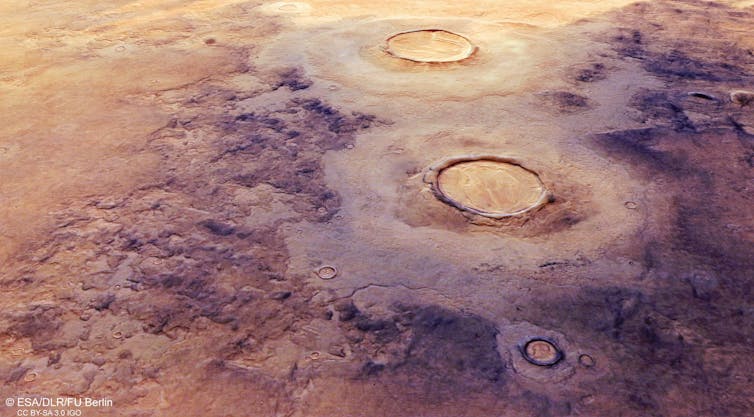

Titan’s wet surface?

The surface could be shaped by hydrocarbon rain and flowing rivers, and the shorelines of any lakes could be carved by tides. Titan’s environment – preserved in the deep freeze of the outer solar system – reminds many scientists of what the very young Earth might have been like and could provide important clues to understanding the chemical processes that led to life.

Descent details

When Huygens separates from Cassini at 9 P.M. EST December 24, it will pull away at less than 1 mile per hour. The separation maneuver will also impart a spin of 7 revolutions per minute to Huygens to ensure its stability on the 3-week journey to Titan. The only instrument on Huygens that will operate during the trip is a system of alarm clocks designed to wake the spacecraft a few hours before it hits the atmosphere’s fringe the morning of January 14, 2005.

During Huygens’ first 3 minutes inside the atmosphere, friction will slow the spacecraft from 11,200 miles per hour (18,025 km/h) to 870 miles per hour (1,400 km/h) and raise the temperature of the heat shield to more than 3,000° F (1,650° C). Robotic controls then will release a series of parachutes to slow the spacecraft further and expose science instruments to the atmosphere.

Four instruments will study the atmosphere’s temperature, pressure, density, wind speed, and composition during the expected 2.5-hour-long descent. Shortly before Huygens reaches Titan’s surface, a camera will photograph the area around the landing site. (A lamp will turn on just before touchdown to augment the weak sunlight, which is 1,000 times dimmer than at Earth’s surface.)

Huygens should hit the surface at about 10 miles per hour (16 km/h). Huygens’ batteries should survive for another 30 minutes. A suite of instruments will determine the physical properties of the surface – whether the probe lands on solid ground or in a hydrocarbon lake. All the information will be sent to the Cassini orbiter, which will relay the precious information to Earth.

Fast facts about the mission:

Links to public-domain images of Cassini and Huygens

****Copy and paste links, if they don’t work directly****

These links show Huygens being jettisoned from Cassini:

http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/multimedia/images/image-details.cfm?imageID=616

http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/multimedia/images/image-details.cfm?imageID=624

http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/multimedia/images/image-details.cfm?imageID=628

The following show Huygens on or near Titan’s surface:

http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/multimedia/images/image-details.cfm?imageID=627

http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/multimedia/images/image-details.cfm?imageID=625

http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/multimedia/images/image-details.cfm?imageID=621

Astronomy magazine’s extensive Cassini coverage

In-depth information on this landmark mission can be found in “Journey to Saturn,” an 8-page feature in the January 2004 Astronomy magazine. The article includes a graphical summary of Cassini’s long journey; images of Saturn’s atmosphere; top 10 (projected) Cassini mission highlights; information on the spacecraft namesakes: Giovanni Cassini and Christiaan Huygens; a summary of Huygens’ instruments – with a full-color illustration of Huygens’ descent; and, an overview of Saturn’s medium-size moons. For a copy of this issue, please contact Matt Quandt: mquandt@astronomy.com or 262.796.8776 x.419.

Astronomy magazine and Astronomy.com will keep you abreast of the latest findings from both Cassini and the Huygens probe.