Recent images of Titan from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft affirm the presence of lakes of liquid hydrocarbons by capturing changes in the lakes brought on by rainfall.

For several years, Cassini scientists have suspected that dark areas near the north and south poles of Saturn’s largest satellite might be liquid-filled lakes. An analysis published January 29 in the journal of Geophysical Research Letters of recent pictures of Titan’s south polar region reveals new lake features not seen in images of the same region taken a year earlier. The presence of extensive cloud systems covering the area in the intervening year suggests that the new lakes could be the result of a large rainstorm, and some lakes may owe their presence, size, and distribution across Titan’s surface to the moon’s weather and changing seasons.

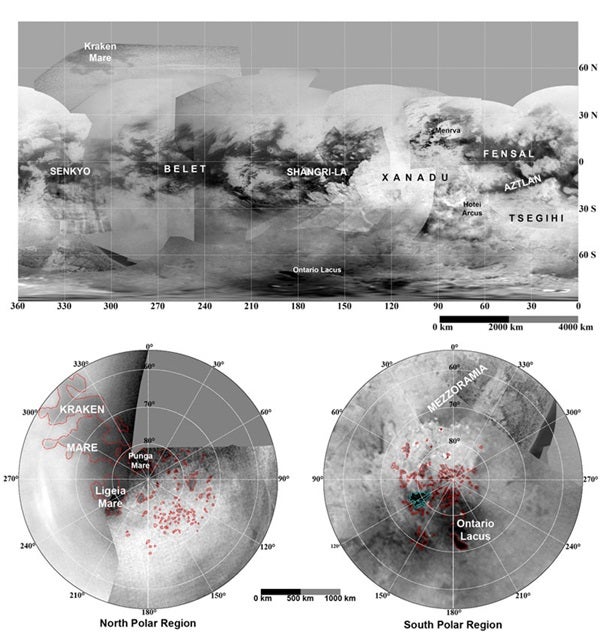

The high-resolution cameras of Cassini’s Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS) have now surveyed nearly all of Titan’s surface at a global scale. An updated Titan map, released yesterday by the Cassini Imaging Team, includes the first near-infrared images of the leading hemisphere portion of Titan’s northern “lake district” captured August 15-16, 2008. (The leading hemisphere of a moon is that which always points in the direction of motion as the moon orbits the planet.) These ISS images complement existing high-resolution data from Cassini’s Visible and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) and RADAR instruments.

Such observations have documented greater stores of liquid methane in the northern hemisphere than in the southern hemisphere. And, as the northern hemisphere moves toward summer, Cassini scientists predict large convective cloud systems will form there, and precipitation greater than that inferred in the south could further fill the northern lakes with hydrocarbons.

Some of the north polar lakes are large. If full, Kraken Mare – at 154,400 square miles (400,000 square kilometers) – would be almost five times the size of North America’s Lake Superior. All of the north polar dark “lake” areas observed by ISS total more than 196,900 square miles (510,000 square kilometers) – almost 40 percent larger than Earth’s largest “lake,” the Caspian Sea.

However, evaporation from these large surface reservoirs is not great enough to replenish the methane lost from the atmosphere by rainfall and by the formation and eventual deposition on the surface of methane-derived haze particles.

“A recent study suggests that there’s not enough liquid methane on Titan’s surface to re-supply the atmosphere over long geologic timescales,” said Elizabeth Turtle, Cassini imaging team associate at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab in Laurel, Maryland, and lead author of the publication. “Our new map provides more coverage of Titan’s poles, but even if all of the features we see there were filled with liquid methane, there’s still not enough to sustain the atmosphere for more than 10 million years.”

Combined with previous analyses, these new observations suggest that underground methane reservoirs must exist.

Titan is the only satellite in the solar system with a thick atmosphere in which a complex organic chemistry occurs. “It’s unique,” Turtle said. “How long Titan’s atmosphere has existed or can continue to exist is still an open question.”

That question and others related to the moon’s meteorology and its seasonal cycles may be better explained by the distribution of liquids on the surface. Scientists also are investigating why liquids collect at the poles rather than low latitudes, where dunes are common instead.

“Titan’s tropics may be fairly dry because they only experience brief episodes of rainfall in the spring and fall as peak sunlight shifts between the hemispheres,” said Tony DelGenio of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, a co-author and a member of the Cassini imaging team “It will be interesting to find out whether or not clouds and temporary lakes form near the equator in the next few years.”

Titan and the transformations on its surface brought about by the changing seasons will continue to be a major target of investigation throughout Cassini’s Equinox mission.