Looking almost 11 billion years into the past, astronomers have measured the motions of stars for the first time in a very distant galaxy and clocked speeds upwards of one million miles per hour (1,600,000 km/hour), about twice the speed of our Sun through the Milky Way.

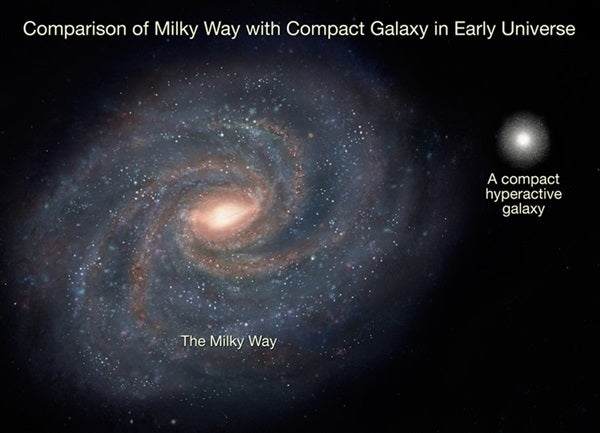

The fast-moving stars shed new light on how these distant galaxies, which are a fraction the size of our Milky Way, may have evolved into the full-grown galaxies seen around us today.

“This galaxy is very small, but the stars are whizzing around as if they were in a giant galaxy that we would find closer to us and not so far back in time,” said Pieter van Dokkum, professor of astronomy and physics at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, who led the study. It is still not understood how galaxies like these, with so much mass in such a small volume, can form in the early universe and then evolve into the galaxies we see in the more contemporary nearby universe that is about 13.7 billion years old.

The work by the international team combined data collected using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope with observations taken by the 8-meter Gemini South telescope in Chile.

According to van Dokkum, “The Hubble data, taken in 2007, confirmed that this galaxy was a fraction the size of most galaxies we see today in the more evolved, older universe. The giant 8-meter mirror of the Gemini telescope then allowed us to collect enough light to determine the overall motions of the stars using a technique not very different from the way police use laser light to catch speeding cars.” The Gemini near-infrared spectroscopic observations required an extensive 29 hours on the sky to collect the extremely faint light from the distant galaxy, which goes by the designation 1255-0.

“By looking at this galaxy, we are able to look back in time and see what galaxies looked like in the distant past when the universe was very young,” said team member Mariska Kriek of Princeton University. 1255-0 is so far away that the universe was only about 3 billion years old when its light was emitted.

Astronomers confess that it is a difficult riddle to explain how such compact, massive galaxies form, and why they are not seen in the current, local universe. “One possibility is that we are looking at what will eventually be the dense central region of a very large galaxy,” said team member Marijn Franx of Leiden University in The Netherlands. “The centers of big galaxies may have formed first, presumably together with the giant black holes that we know exist in today’s large galaxies that we see nearby.”

To witness the formation of these extreme galaxies, astronomers plan to observe galaxies even further back in time in great detail. By using the Wide Field Camera 3, which was recently installed on the Hubble Space Telescope, such objects should be detectable. “The ancestors of these extreme galaxies should have quite spectacular properties as they probably formed a huge amount of stars, in addition to a massive black hole, in a relatively short amount of time,” said van Dokkum.

This research follows recent studies revealing that the oldest, most luminous galaxies in the early universe are very compact yet surprisingly have stellar masses similar to those of present-day elliptical galaxies. The most massive galaxies we see in the local universe which have a mass similar to 1255-0 are typically five times larger than a young compact galaxy. How galaxies grew so much in the past 10 billion years is an active area of research, and understanding the dynamics in these young compact galaxies is a key piece of evidence in eventually solving this puzzle.