Key Takeaways:

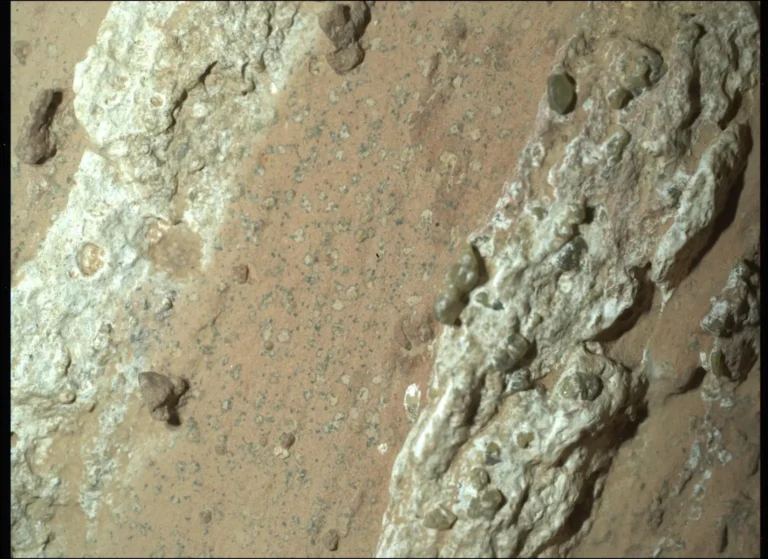

Patterns in the ground near Mars’ Athabasca Vallis suggest the region once contained a frozen sea, says an international team of planetary geologists reporting this week at the first Mars Express Science Conference in Noordwijk, the Netherlands. Moreover, they say, plate-like surface features that resemble pack ice on Earth may still harbor buried blocks of ice, protected by a layer of volcanic ash.

The region lies at 5° north latitude and 150° east longitude, about 730 miles (1,180 kilometers) south of Elysium Mons. It also lies at the west end of Athabasca Vallis, an outflow channel leading from Cerberus Fossae, which scientists believe was a source of both lava and water flows.

Says Murray, pointing to Cerberus, “It appears you have an eruption of water from deep underground — one of those catastrophic floods that flowed down and covered the whole area south of Elysium Mons.”

Gushing floods

Where the water ended up forms a generally enclosed basin, about 500 by 560 miles (800 by 900 km) and roughly 150 feet (45 meters) deep — “similar in size and depth to the North Sea” on Earth, says the team. Water flowing into the basin would have ponded and frozen over quickly.

As Murray’s team reconstructs the events, eruptions at Cerberus could have shot volcanic ash into the air while liberating the flood of water that filled the basin through Athabasca Vallis. The ash settled on the freezing basin, mingling with the ice and preventing it from immediately evaporating in the thin air.

The lighter-hued areas between the large plates are similar to “leads,” or open water channels between Arctic ice floes. Murray notes they are about 10 feet (3 meters) on average lower than the plates. He attributes this to evaporation caused when the ash-rich ice covering the basin cracked, exposing fresh water containing less insulating ash and sediment. The fresher water would have evaporated more than the rubble-covered floes.

Not lava

Planetary scientists have interpreted similar-looking features elsewhere on Mars as rafts of solid lava carried by flood basalts. Murray’s team dismisses the idea in this case. Basalt hardens within a few years at most, they note, and the areas between the plates have crater-count ages of about 4 million years, a million years younger than the plates themselves. Mantled with ash, the ice covering the basin could last that long, they calculate.

Another tipoff for ice is the extraordinary flatness of the plates. “They have a relief of plus or minus 5 meters [15 feet] over a measured 65 kilometers [40 miles],” says Murray. “That’s the slope of the tide coming into an estuary on Earth.”

Ice still there?

Murray and his team think there’s a good chance the ice is still there. “With the submerged craters,” he says, “you see they still contain 90 or 95 percent of the infill. This suggests most of the ice is still in the craters.” Also, notes the team, the surface is too horizontal for a natural basin whose floor varies in altitude. If the ice were gone, the floes’ height would vary more.

Another finding reported at the Mars Express Science Conference increased the interest in this region. Vittorio Formisano of Italy’s Institute of Physics and Interplanetary Space announced that the Planetary Fourier Spectrometer (of which he is chief scientist) had detected elevated concentrations of methane in the atmosphere over the region. Other scientists, however, dispute the amount of the methane concentrations. On Earth, nearly all methane has a biological origin, but the gas can be produced by volcanic processes.

Given the chance that residual ice may remain from this sea, Murray says “this would be a prime candidate area” for searches for life.