Though still under construction, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the South Pole is already delivering scientific results, including an early finding about a phenomenon the telescope was not even designed to study.

IceCube captures signals of notoriously elusive but scientifically fascinating subatomic particles called neutrinos. The telescope focuses on high-energy neutrinos that travel through Earth, providing information about faraway cosmic events such as supernovae and black holes in the part of space visible from the Northern Hemisphere.

However, one of the challenges of detecting these relatively rare particles is that the telescope is constantly bombarded by other particles, including many generated by cosmic rays interacting with Earth’s atmosphere over the southern half of the sky. For most IceCube neutrino physicists, these particles are simply background noise, but University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers Rasha Abbasi and Paolo Desiati, with collaborator Juan Carlos Diaz-Velez, recognized an opportunity in the cosmic-ray data.

“IceCube was not built to look at cosmic rays. Cosmic rays are considered background,” Abbasi said. “However, we have billions of events of background downward cosmic rays that ended up being very exciting.”

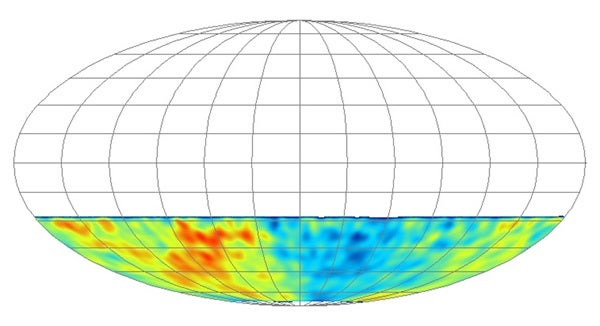

Abbasi saw an unusual pattern when she looked at a sky map of the relative intensity of cosmic rays directed toward Earth’s Southern Hemisphere, with an excess of cosmic rays detected in one part of the sky and a deficit in another. A similar lopsidedness, called “anisotropy,” has been seen from the Northern Hemisphere by previous experiments, Abbasi said, but its source is still a mystery.

“At the beginning, we didn’t know what to expect,” said Abbasi. “To see this anisotropy extending to the Southern Hemisphere sky, it’s an additional piece of the puzzle around this enigmatic effect, whether it’s due to the magnetic field surrounding us or to the effect of a nearby supernova remnant, we don’t know.”

One possible explanation for the irregular pattern is the remains of an exploded supernova, such as the relatively young nearby supernova remnant Vela, whose location corresponds to one of the cosmic-ray hotspots in the anisotropy sky map. The pattern of cosmic rays also reveals more detail about the interstellar magnetic fields produced by moving gases of charged particles near Earth, which are difficult to study and poorly understood.

“We can predict some models, but we don’t have concrete knowledge of the magnetic field on small scales,” Abbasi said. “It would be really nice if we did — we would have made a lot more progress in the field.”

Because nearly all cosmic signals are influenced by the interstellar magnetic fields, a better overall picture of these fields would aid a large range of physics and astronomy studies, Abbasi said, adding that their newly reported findings rule out some proposed theories about the source of the Northern Hemisphere anisotropy.

The IceCube group is currently extending its analysis to improve its understanding of the anisotropy on a more detailed scale and delve further into its possible causes. While the newly published study used data collected in 2007 and 2008 from just 22 strings of optical detectors in the IceCube telescope, they are now analyzing data from 59 of the 79 strings that are in place to date. When completed in 2011, the telescope will fill a cubic kilometer of Antarctic ice with 86 strings containing more than 5,000 digital optical sensors.

“This is exciting because this effect could be the ‘smoking gun’ for our long-sought understanding of the source of high-energy cosmic rays,” said Abbasi.