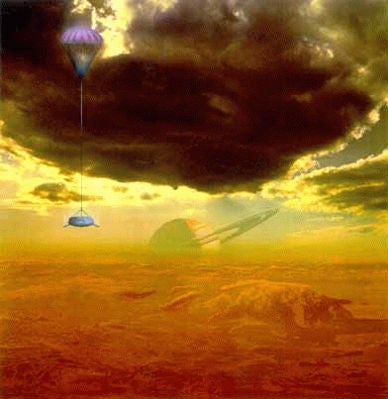

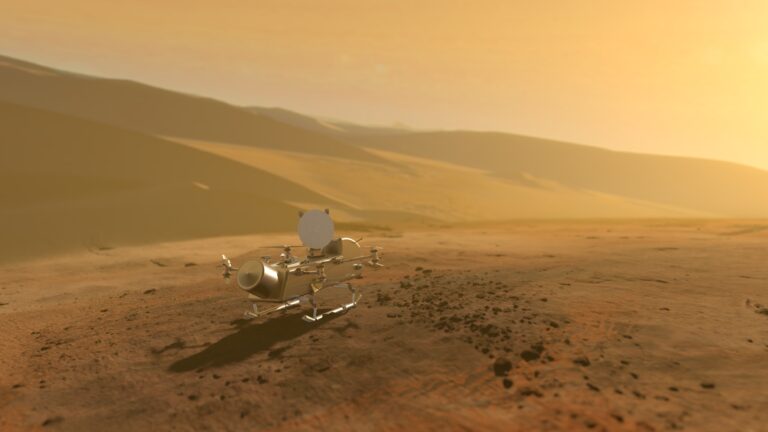

In November 1997, NASA and the European Space Agency launched the Cassini spacecraft and its Huygens probe on its way to explore Saturn and its large, mysterious moon, Titan. Five and a half years later, we’re still not sure what the Huygens probe will find when it descends through Titan’s atmosphere to the moon’s surface. But now, astronomers have taken a peek through some small spectral “windows” to learn that Huygens may land on a large region of icy bedrock when it touches down in January 2005.

Since its discovery in 1655, Titan has remained a mystery to scientists who have wondered what lies beneath the moon’s thick, hazy atmosphere. Even after the Pioneer and Voyager spacecraft flew past Saturn in the late 1970s and early ’80s, Titan appeared to be little more than a foggy, orange orb.

Still, scientists have managed to learn a few things about Titan’s atmospheric cloak. Ten times as massive as Earth’s atmosphere, it is primarily made of nitrogen and methane. Incoming ultraviolet light from the sun destroys methane molecules, leading to the formation of organic compounds, which scientists suspect produce an organic “rain” from Titan’s methane clouds. Researchers have estimated that, if this process has been ongoing for the entire 4.6 billion years of Titan’s existence, about 800 meters of liquid and solid sediment should blanket the surface, perhaps forming huge lakes or oceans.

“This is somewhat surprising because Titan is believed to have a lot of organic gook on its surface,” Griffith adds.

The results may make sense in relation to Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based observations of Titan’s surface. Since 1994, these near-infrared observations have revealed large, dark and light patches on Titan’s surface.

“It’s not clear what the darker material is, but one possibility is that it is these organic liquids and sediments,” Griffith states. “The images, taken together with our results, suggest that organic stuff is moved around on the surface in such a way as to expose [bright] bedrock ice.”