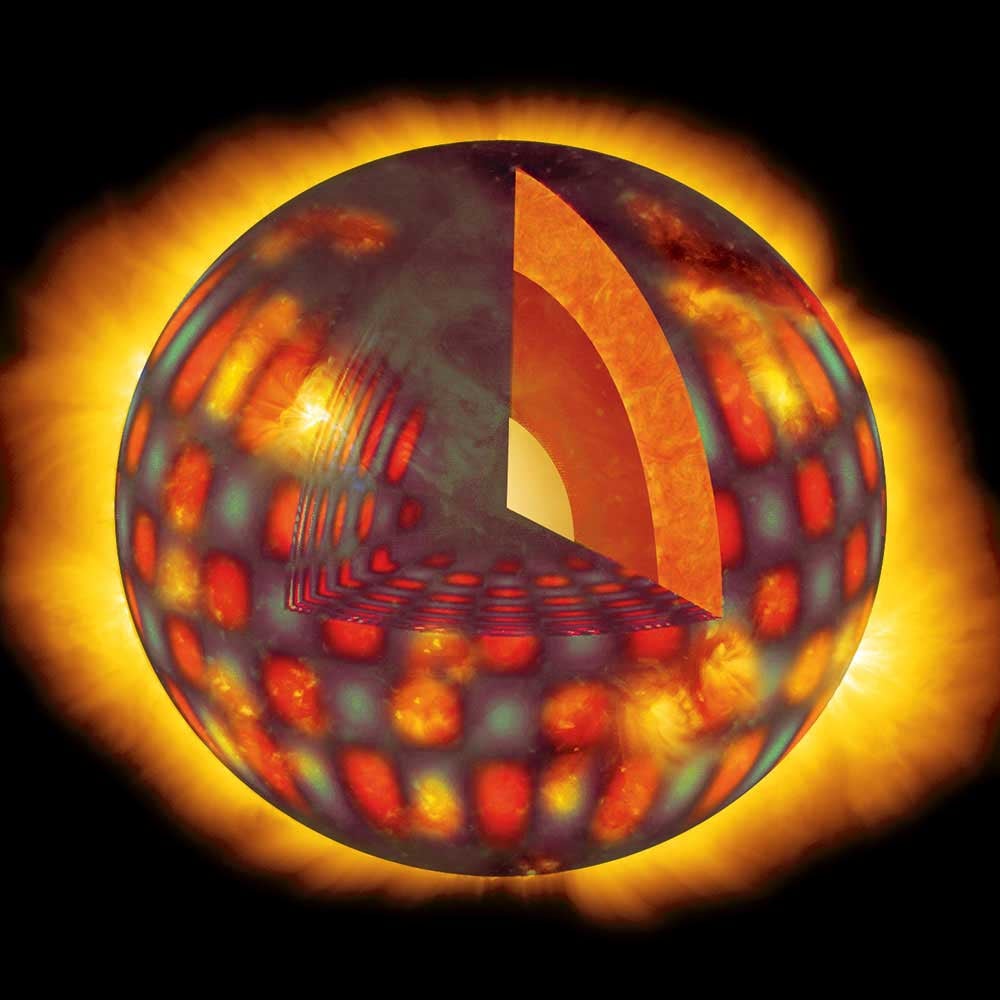

The Sun vibrates like a musical instrument, similar to an organ. Instead of the room-temperature air in an organ pipe, though, hot hydrogen and helium gas, whose temperatures vary with depth, fills the Sun. Instead of a cylindrical pipe, our star is a sphere, its shape molded by gravity, with no solid container. And while an organist forces pressurized air into a pipe to make it resonate, natural turbulence in the gas near the Sun’s surface causes its vibrations. This generates sound waves that travel into the Sun, are reflected when they reach its surface again, and cause the star to resonate in millions of frequencies.

Astronomers record these frequencies, not for their interstellar iPods, but to probe the Sun’s interior, the same way geophysicists use earthquake waves to study Earth’s interior. Because of this parallel, the technique is called helioseismology.

The Sun’s “loudest pitch” is about 0.0033 Hertz (Hz) — some 6,000 times below the lowest tone audible to a human ear. Music-minded astronomers take the frequencies of solar oscillations, multiply them by a million, and convert them into a soundtrack you can hear — although not quite the same as the microphone and sound system at a concert. But would the noise from the Sun’s turbulence be loud enough and in the right frequency range to hear?

Loudness depends on how much the pressure changes at the microphone (or ear). At the depth from which visible light can first escape the Sun (a few hundred kilometers), the pressure fluctuations need be only 0.1 percent to be as loud as a chainsaw. But the pitch of a chainsaw’s whine is about 4,000 Hz, a million times higher than the frequencies of the smallest turbulent eddies in supercomputer models of the solar atmosphere. Even if the Sun had waves a hundred meters from crest to crest, short enough to be the lowest audible pitch, you wouldn’t hear it because there’s no solid surface against which those waves could crash.

The shallows of the solar sea are indeed a noisy place, but not to human ears. The Sun is singing the sound of silence.

University of British Columbia, Vancouver