NASA’s Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) spacecraft has made the first observations of fast hydrogen atoms coming from the Moon, following decades of speculation and searching for their existence.

During spacecraft commissioning, the IBEX team turned on the IBEX-Hi instrument, built primarily by Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in San Antonio, and the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. The device measures atoms with speeds from about .5 million to 2.5 million miles (.8 million to 4.0 million kilometers) per hour. Its companion sensor, IBEX-Lo, built by Lockheed Martin in Bethesda, Maryland; the University of New Hampshire in Durham; NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland; and the University of Bern in Switzerland, measures atoms with speeds from about 100,000 to 1.5 million miles (161,000 to 2.4 million kilometers) per hour.

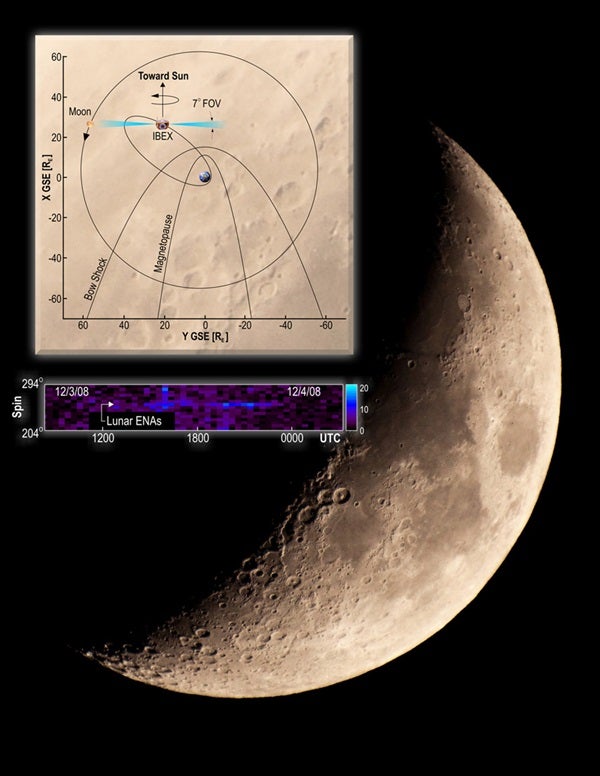

“Just after we got IBEX-Hi turned on, the Moon happened to pass right through its field of view, and there they were,” said David J. McComas, IBEX principal investigator and assistant vice president of the SwRI Space Science and Engineering Division. “The instrument lit up with a clear signal of the neutral atoms being detected as they backscattered from the Moon.”

The solar wind, the supersonic stream of charged particles that flows out from the Sun, moves out into space in every direction at speeds of about a million miles (1.6 million kilometers) per hour. The Earth’s strong magnetic field shields our planet from the solar wind. The Moon, with its relatively weak magnetic field, has no such protection, causing the solar wind to slam onto the Moon’s sunward side.

From its vantage point in space, IBEX sees about half of the Moon — one quarter of it is dark and faces the nightside (away from the Sun) while the other quarter faces the dayside (toward the Sun). Solar wind particles impact only the dayside, where most of them are embedded in the lunar surface, while some scatter off in different directions. Many of the scattered ones become neutral atoms in this reflection process by picking up electrons from the lunar surface.

The IBEX team estimates that only about 10 percent of the solar wind ions reflect off the sunward side of the Moon as neutral atoms, while the remaining 90 percent is embedded in the lunar surface. Characteristics of the lunar surface, such as dust, craters, and rocks, play a role in determining the percentage of particles that become embedded and the percentage of neutral particles that scatter, as well as their direction of travel.

McComas says the results also shed light on the “recycling” process undertaken by particles throughout the solar system and beyond. The solar wind and other charged particles impact dust and larger objects as they travel through space, where they backscatter and are reprocessed as neutral atoms. These atoms can travel long distances before they are stripped of their electrons and become ions, and the process begins again.

The combined scattering and neutralization processes now observed at the Moon have implications for interactions with objects across the solar system, such as asteroids, Kuiper Belt objects, and other moons. The plasma-surface interactions occurring within protostellar nebula — the region of space that forms around planets and stars — as well as exoplanets, planets around other stars, also can be inferred.

IBEX’s primary mission is to observe and map the complex interactions occurring at the edge of the solar system, where the solar wind runs into interstellar material from the rest of the galaxy. The spacecraft carries the most sensitive neutral atom detectors ever flown in space, enabling researchers to not only measure particle energy, but also to make precise images of where they are coming from.

Around the end of the summer, the team will release the spacecraft’s first all-sky map showing the energetic processes occurring at the edge of the solar system. The team will not comment until the image is complete, but McComas hints, “It doesn’t look like any of the models.”