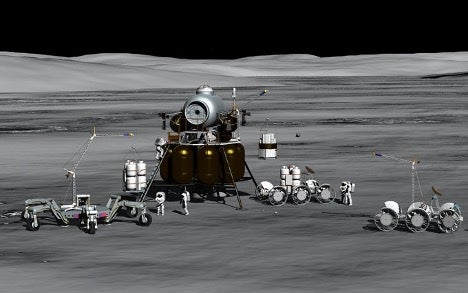

NASA Altair lunar module is shown fitted with cargo pods. The lander is proposed as the initial workhorse for lunar development, capable of ferrying 15 metric tons of equipment to and around the lunar surface. Once a lunar station is established, raw material extraction and orbital assembly could proceed.

Over the course of the next 50 years, even conservative estimates suggest another 2 billion to 3 billion people will enter the market for cars, houses, and the latest tech gadgets. And as the crest of the population wave looms, so do the insistent alarm-bells of human impact — collapsed fisheries, exploited tar sands, and scorched forests devoid of wildlife.

It’s a grim picture, one made even more poignant by wall-to-wall coverage of yet another catastrophic wildfire season in the midst of a pandemic. But it’s also a reality we must face head-on if we aim to continue to grow and thrive as both a species and planet. However, the age-old question remains: Where will we get the resources?

The solution, according to some, is outer space.

At the 2016 Recode conference, Jeff Bezos breezily suggested that we “don’t want to live in a retrograde world where we have to freeze population growth.” In his vision of the future, CNBC reported, “Earth will be zoned residential and light industrial.” Operations like mining, which take a heavy toll on the environment, would be moved off Earth.

It’s a magnificently far-fetched idea, one that’s more at home in the pages of a novel than on the front page of the New York Times. But humanity is already moving in that direction.

The space rush

In this rendition of the human timeline, we don’t abandon heavy industry. We learn to manufacture what we need to maintain our lives in the cold vacuum of space, just in time to give Earth a break.

The race to build an industrial foundation in space has already begun, too: Musk promises Mars Base Alpha by 2028; Bezos’ own Blue Origin is working on a “sustained human presence on the Moon;” and NASA’s Lunar Gateway, a permanent orbital station, is set to go into operation by the end of the decade.

In 40 years, launch costs have fallen from $85,000 per kilogram to less than $1,000/kg, and NASA hopes to get this under $100/kg in the next few years. This trajectory makes space-mining advocate and Skycorp CEO Dennis Wingo more certain than ever that we are on the cusp of a new era of space mining. He reiterates to Astronomy that “industrial activity on the Moon is how we can make things better here on Earth.”

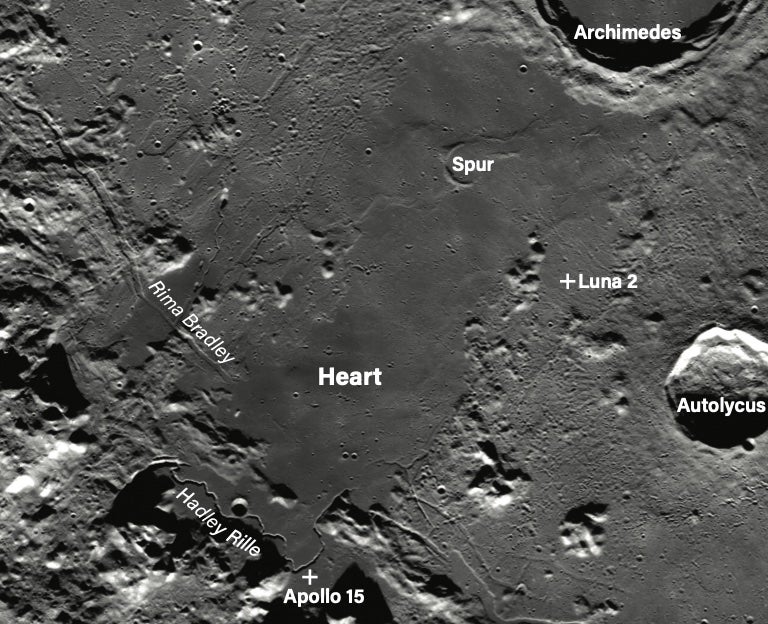

Instead of returning raw materials from the Moon to Earth, which Wingo suggests would “be kind of like shipping dirt from Jakarta to the U.S.,” the space-mining industry would chase profits by finding ways to process raw materials directly at their icy, remote sources. On the horizon, he envisions a solar-powered lunar base capable of producing the gigawatt-level power needed for mining.

The lunar surface, in his eyes, is an incredibly efficient place for industrial processes. Wingo calculates that “the best vacuum you can get on the Earth is about 10-5 Torr.” (That’s about one one-hundred-millionth the standard pressure at sea level.) “But on the lunar surface, you have infinite quantities of 10-12 Torr.” Under those conditions, it’s possible to efficiently process raw lunar regolith — the pulverized rock that covers the Moon’s surface — into valuable materials.

As you “heat regolith to over 2,000 degrees Celsius [3,632 degrees Fahrenheit], the metal oxides it contains dissociate into metal and oxygen,” says Wingo. “That waste oxygen can be compressed and stored or used for breathing.” This creates a self-sustaining system that doesn’t entirely avoid waste products, but still keeps the caustic remnants of mining far from the life-giving ecosystems upon which we depend for survival.

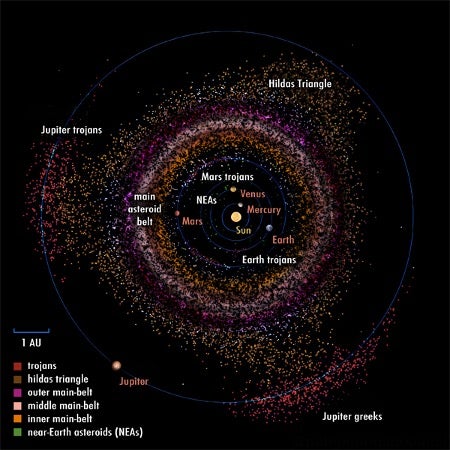

The way Wingo sees it, the Moon could be a testing grounds for new extraction techniques, power-plants, and assembly protocols. Proven operations could then radiate outward from Earth and the Moon into the asteroid belt, where the mineral wealth of the solar system has been estimated to run into the quintillions of dollars. Though the upfront costs of establishing extraterrestrial industry is extremely high, the eventual returns could be beyond the greatest riches the world has ever seen.

Keeping it above board

The financial and ecological incentives of space mining make it easy for planetary scientist Philip Metzger of the Space Institute at the University of Central Florida to agree with Wingo. Reached by email, Metzger mused that “it is inevitable that we will move in this direction very soon. As robotics and artificial intelligence improve, and as the environmental impact cost of [these industries] on Earth continues to increase,” space-based extraction will become more and more viable. However, there is some concern that without careful transparency and legislative measures, a new industrial space rush could result in unforeseen catastrophe.

Former NASA navigator, Moriba Jah, now professor in Aerospace Engineering and Engineering Mechanics at the University of Texas, has some ideas about the healthiest ways to approach outer-space resource extraction. In this next phase of expansion, Jah imagines that we take our cues from ancient indigenous land-management practices.

When assessing a new territory like the Moon or an asteroid, Jah says “it doesn’t mean that we don’t exploit resources. It doesn’t even mean that we don’t make lots of money. What it means is that we don’t treat it as something that we own.” Guided by this mentality, legislation would designate mineral-rich space territory as a shared resource. The price for access, then, becomes the burden of stewardship. And the tenets that could be used for drafting such legislation, Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), have been in development since the 1980s, meaning they could serve as a robust basis for moving forward.

One thing is certain — our planet could use a breather. The mineral wealth of outer space is apparent, and the question of how we will provide for another few billion of our brothers and sisters is never far from the surface. Space mining is one promising multipolar solution, but the burden will be on us to prevent ecological mistakes of previous generations.