It’s not exactly a scenic spot: hot tar oozes up to the surface, cooling into a patchwork crust, and bubbles of methane and carbon dioxide pop at the surface. But even here, life has a foothold. Within the bubbling hydrocarbon stew, a menagerie of bacteria and archaea feast on heavy hydrocarbons and exhale methane.

This place is not an alien sea, but located right here on Earth. It’s Pitch Lake — a lake of asphalt formed as pitch seeps up from a fault deep beneath the islands of Trinidad and Tobago, mixing with mud and gases on the way. And it may be the closest thing we have to an Earthly analogue for life and its habitat on another world, including Saturn’s largest moon, Titan.

But just how good is this analogy?

Alien landscapes on Earth

Astrobiologists often look to extreme environments here on Earth to see what niches life might occupy on other worlds. They use those analogues to learn where to look for life on places like Mars, Europa, or Enceladus. A few, like Washington State University astrobiologist Dirk Schulze-Makuch and his colleagues, have studied Pitch Lake’s microbes to learn whether the microbes have evolved traits that could also aid life on hydrocarbon-rich worlds like Titan.

“The closest thing that I could really think of are pockets of nearly pure oil deposits in the crust of the Earth that had been isolated from water because they were sandwiched between two impermeable sediments, for example,” says Cornell University planetary scientist Jonathan Lunine.

Although Pitch Lake still isn’t alien enough to be a proper analogue for Titan, it’s the closest we can get outside the confines of a lab or computer simulation. “It is quite difficult to say how close of an analogy [it is]. I mean, we don’t have anything better, let’s say it like that,” says Schulze-Makuch.

Both Pitch Lake and Titan’s seas are mostly-liquid bodies of hydrocarbons, containing some solid components and slush. But Pitch Lake contains mainly heavier hydrocarbons like asphalt, while lighter compounds like methane and ethane are more common on Titan. And of course, the deep cold of Titan is a far cry from the tropical warmth of Trinidad. The biggest debate about Pitch Lake’s value as a Titan analogue, however, centers on the liquid water present in the first, but not the second.

But Pitch Lake may still have a few lessons to teach us about where and how to look for life on such an alien world.

Where to look

If there is life “as we know it” — as in, Earth-like life — on Titan, it’s likely to live in a pretty specific type of environment. The microbes in Pitch Lake aren’t swimming around in light hydrocarbons like methane and ethane. Pitch Lake contains heavier hydrocarbons, like asphalt. Even then, the microbes aren’t living directly in that asphalt; they’re living in water droplets of about one to three microliters each, suspended in the hydrocarbon lake. The microbes cluster around the droplets’ surfaces to snack on those hydrocarbons, but they remain safely immersed in water — just like every other living cell on Earth.

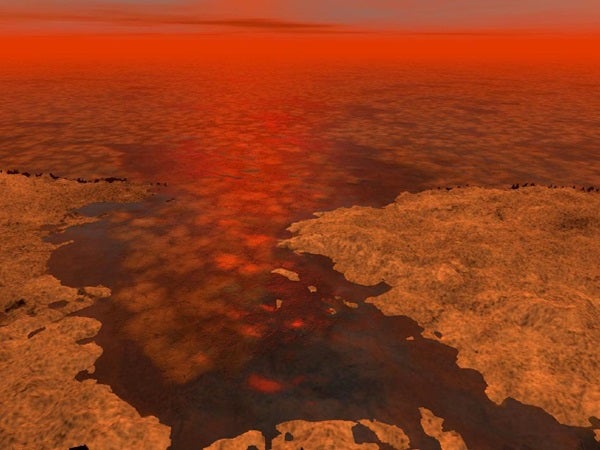

There’s a chance this kind of environment may exist in a few places on Titan. To find it, you’d have to look at the bottom of the deepest parts of its hydrocarbon lakes — places where heavier hydrocarbons have settled to the bottom and might come into contact with geothermally-heated water from much deeper within Titan’s icy crust.

Although Titan’s surface is far too cold for liquid water, some planetary scientists say that geothermal activity may create hotspots where a slurry of water and ammonia could seep out of the icy crust into the hydrocarbon sea, or bubble to the surface in geysers or cryovolcanoes. These spots may even provide enough heat to enable chemical reactions that could lead to life, and Pitch Lake could be a decent analogue for a niche like this.

“If that water were liquid and not tied up into ice, then you might have exactly the same chemistry situation as you do with someplace like Pitch Lake,” says NASA astrobiologist Mary Voytek. But planetary scientists are still debating whether geological activity on Titan could actually produce that kind of environment.

“It’s a dynamic planetary body, so you would think that you have quite a bit of microenvironments,” says Schulze-Makuch. “As you go in the subsurface, especially at the bottom of those hydrocarbon lakes, and there’s some intersection with geysers, ammonia-water slurries, and this kind of stuff, then you would expect quite a bit of diversity of environment.”

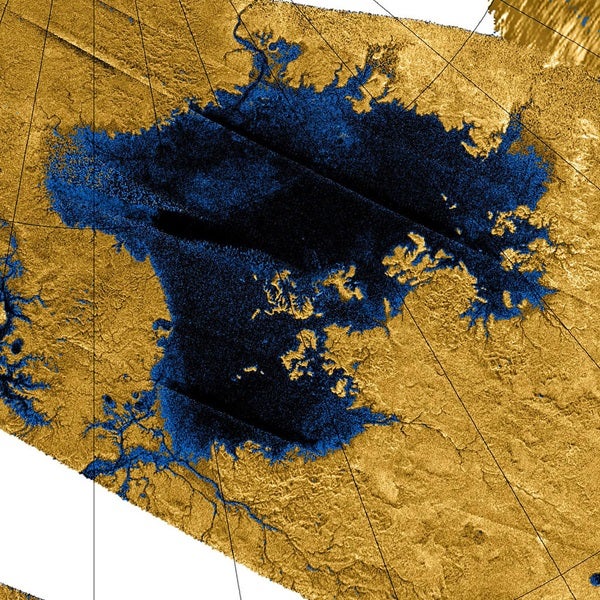

Others, like Lunine, disagree. “There really isn’t any evidence for geothermal heating,” he says — while Cassini’s radar data has spotted water ice on lake shores, “there’s no evidence for a lot of heating.” Titan may have a liquid water ocean tens or hundreds of kilometers deep in its icy crust, heated by the planet’s internal warmth, but Lunine and NASA atrobiologist Chris McKay believe it’s buried too deep to ever reach the surface.

“If you postulate water underground on Titan and consider life there then the story changes fundamentally. Then it can be liquid water based life,” says McKay. “But these Titan water oceans, if they exist, are not in reach. The liquid we can get to is liquid methane/ethane.”

The debate underscores how many questions remain about Titan even in the wake of the Cassini-Huygens mission. “There are many clues to Titan, or much information about the physical and chemical environment, we still need to understand,” says Voytek, “but that doesn’t stop astrobiologists from studying what could be possible.”

If the Pitch Lake scenario holds true, however, it means Titan’s habitable niches are on a very small scale — like tiny droplets of water suspended in liquid hydrocarbon.

“We think on a different scale; for a microbe, a puddle is an ocean,” says Schulze-Makuch. “We have to look on that scale on which the organism lives.” That means we might not be able to spot Titan’s life from afar with an orbiter; to investigate such tiny habitats would probably require a surface sampling mission.

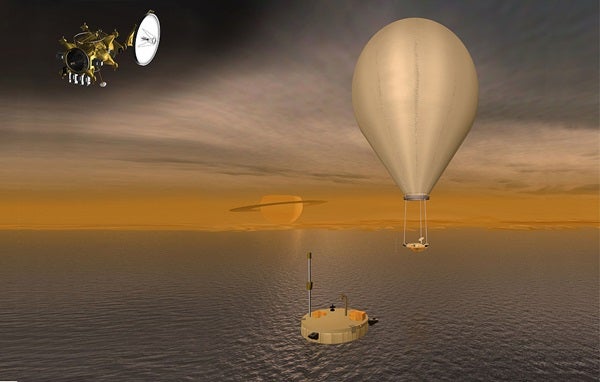

Four years ago, Lunine and his colleagues proposed exactly that: a Discovery-class mission called Titan Mare Explorer, or TiME. Their idea was to land a floating probe in one of Titan’s large northern seas, where it would drift with the current until it reached the shoreline. Along the way, the probe would use a mass spectrometer to sample the hydrocarbon sea and whatever material washed up ashore, looking for complex molecules or patterns that might indicate life.

“It was one of the most romantic mission ideas I’ve ever been involved with,” says Lunine. “You know, to land in an extraterrestrial sea and float around until you reach the shore and then take a picture from the shore, and so there you are on the most alien beach you can possibly imagine.” Romantic or not, NASA chose not to fund the proposed mission.

But if Schulze-Makuch’s micro-environments really exist on Titan, they could make it easier for future missions to find evidence of life, because each one will contain lots of microbes in one spot. These dense communities of organisms will be much easier to detect than if the microbes were just scattered through the whole hydrocarbon sea.

“If these droplets exist, we know they will have a concentrated amount of biomass,” said Voytek. “One of our problems in sampling in environments that are harsh is that they tend to have very low numbers of organisms. You go to the middle of the ocean, and in order to see a bug, you have to filter liters and liters and liters of water to get a signal, and so one of the things we worry about is if we go out to one of these icy moons, we’re going to have to process a lot of material in order to find something.”

Water and life as we know it

Pitch Lake can offer some clues about where to look for life as we know it on Titan. But if McKay and others are correct, and there’s no subsurface liquid water seeping into the depths of Titan’s seas after all — or if life on Titan arose in any other niche on the moon — then Pitch Lake isn’t a good roadmap for where life might be or what it might look like.

“[Pitch Lake] is a hydrocarbon-rich environment and water-challenged. But life there is still [composed of] liquid water on the inside, and to me this greatly limits the relevance to life on Titan,” says McKay. “I don’t think there are any good analogues on Earth for life in the lakes of Titan.”

Most questions about life as we don’t know it simply aren’t going to be answered by a terrestrial analogue. There’s some lab work currently exploring how cell structures might come together in that alien chemistry, but we won’t really know whether life thrives in a sea of methane, or how it works, until we put a ship on Titan.

Trinidad, Titan, and beyond

Cassini’s mission ended with a dive into Saturn’s atmosphere on September 15, and there’s no other mission to the Saturn system planned at this point, so it’s likely to be some time before these questions are answered. In the meantime, even if it’s not a perfect analogue, Pitch Lake is the closest thing to Titan’s Kraken Mare that we have here on Earth. The microbes there don’t have much to say about what kind of truly exotic life might exist on Titan, but they do tell us something about where we might look for life as we know it.

Still, some — like Lunine — remain skeptical about Pitch Lake’s relevance to astrobiology. “What does that tell you? It tells you that Pitch Lake is a great place to go look for life. That’s all it tells you,” he says.

But Pitch Lake may be relevant beyond Titan. It could say something about how life might evolve on hydrocarbon-rich exoplanets yet to be discovered.

“Even if it isn’t relevant on Titan, with the discovery of exoplanets that are of the same size and relative relationship to their stars being a possible place that we could find life, there might be other systems that aren’t as cold that are also hydrocarbon-based,” says Voytek. “So, yes to this being a reasonable analogue. Even if it isn’t perfect, it wouldn’t be surprising if there’s some kind of niche, if not on Titan then somewhere else, beyond our solar system, that this would be relevant.”