By analyzing precise measurements of the velocities of individual bright stars within the Andromeda Galaxy using the Keck telescope in Hawaii, the team has managed to separate out stars, tracing out a thick disk from those comprising the thin disk, and assess how they differ in height, width, and chemistry.

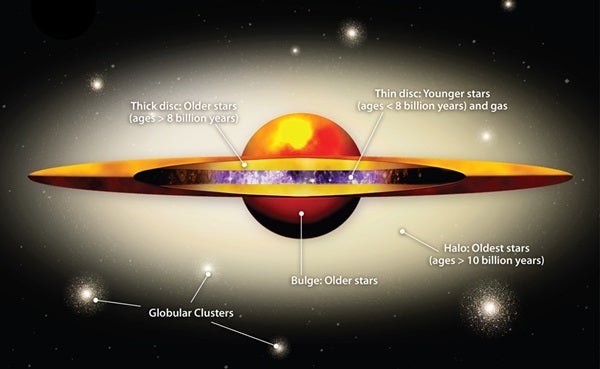

Spiral structure dominates the appearance of large galaxies at the present time, with roughly 70 percent of all stars contained in a flat stellar disk. The disk structure contains the spiral arms traced by regions of active star formation, and surrounds a central bulge of old stars at the core of the galaxy. “From observations of our own Milky Way and other nearby spirals, we know that these galaxies typically possess two stellar disks, both a thin and a thick disk,” said Michelle Collins from Cambridge University’s Institute of Astronomy in the United Kingdom. The thick disk consists of older stars whose orbits take them along a path that extends both above and below the more regular thin disk.

“The classical thin stellar disks that we typically see in Hubble imaging result from the accretion of gas towards the end of a galaxy’s formation,” Collins said, “whereas thick disks are produced in a much earlier phase of the galaxy’s life, making them ideal tracers of the processes involved in galactic evolution.”

Currently, the formation process of the thick disk is not well understood. Previously, the best hope for comprehending this structure was by studying the thick disk of our own galaxy, but much of this is obscured from our view. The discovery of a similar thick disk in Andromeda presents a much cleaner view of spiral structure. Andromeda is our nearest large spiral neighbor — close enough to be visible to the unaided eye — and can be seen in its entirety from the Milky Way.

Astronomers will be able to determine the properties of the disk across the full extent of the galaxy and look for signatures of the events connected to its formation. It requires a huge amount of energy to stir up a galaxy’s stars to form a thick disk component, and theoretical models proposed include accretion of smaller satellite galaxies or more subtle and continuous heating of stars within the galaxy by spiral arms.

“Our initial study of this component already suggests that it is likely older than the thin disk, with a different chemical composition” said Mike Rich from UCLA. “Future, more detailed observations should enable us to unravel the formation of the disk system in Andromeda, with the potential to apply this understanding to the formation of spiral galaxies throughout the universe.”

“This result is one of the most exciting to emerge from the larger parent survey of the motions and chemistry of stars in the outskirts of Andromeda,” said Scott Chapman, also from the Institute of Astronomy. “Finding this thick disk has afforded us a unique and spectacular view of the formation of the Andromeda system, and will undoubtedly assist in our understanding of this complex process.”

By analyzing precise measurements of the velocities of individual bright stars within the Andromeda Galaxy using the Keck telescope in Hawaii, the team has managed to separate out stars, tracing out a thick disk from those comprising the thin disk, and assess how they differ in height, width, and chemistry.

Spiral structure dominates the appearance of large galaxies at the present time, with roughly 70 percent of all stars contained in a flat stellar disk. The disk structure contains the spiral arms traced by regions of active star formation, and surrounds a central bulge of old stars at the core of the galaxy. “From observations of our own Milky Way and other nearby spirals, we know that these galaxies typically possess two stellar disks, both a thin and a thick disk,” said Michelle Collins from Cambridge University’s Institute of Astronomy in the United Kingdom. The thick disk consists of older stars whose orbits take them along a path that extends both above and below the more regular thin disk.

“The classical thin stellar disks that we typically see in Hubble imaging result from the accretion of gas towards the end of a galaxy’s formation,” Collins said, “whereas thick disks are produced in a much earlier phase of the galaxy’s life, making them ideal tracers of the processes involved in galactic evolution.”

Currently, the formation process of the thick disk is not well understood. Previously, the best hope for comprehending this structure was by studying the thick disk of our own galaxy, but much of this is obscured from our view. The discovery of a similar thick disk in Andromeda presents a much cleaner view of spiral structure. Andromeda is our nearest large spiral neighbor — close enough to be visible to the unaided eye — and can be seen in its entirety from the Milky Way.

Astronomers will be able to determine the properties of the disk across the full extent of the galaxy and look for signatures of the events connected to its formation. It requires a huge amount of energy to stir up a galaxy’s stars to form a thick disk component, and theoretical models proposed include accretion of smaller satellite galaxies or more subtle and continuous heating of stars within the galaxy by spiral arms.

“Our initial study of this component already suggests that it is likely older than the thin disk, with a different chemical composition” said Mike Rich from UCLA. “Future, more detailed observations should enable us to unravel the formation of the disk system in Andromeda, with the potential to apply this understanding to the formation of spiral galaxies throughout the universe.”

“This result is one of the most exciting to emerge from the larger parent survey of the motions and chemistry of stars in the outskirts of Andromeda,” said Scott Chapman, also from the Institute of Astronomy. “Finding this thick disk has afforded us a unique and spectacular view of the formation of the Andromeda system, and will undoubtedly assist in our understanding of this complex process.”