The solar system’s planets surely will take a backseat to the comet, but they also offer plenty to celebrate. Mercury enjoys its best morning appearance of 2013. It passes near both Saturn and ISON late this month. While Mars and Jupiter put on their best shows after midnight, Venus dominates the early evening sky. Finally, although the comet may win this month’s grand prize for magnificence, a November 3 total solar eclipse in Africa has to rank a close second.

As darkness falls in November, Venus gleams low in the southwestern sky. It lies 47° east of the Sun on the 1st, its maximum elongation for this apparition. Yet the brilliant planet actually climbs higher in the evening sky as the month progresses.

Solar system geometry explains this apparent contradiction. The ecliptic — the apparent path of the Sun across the sky that the planets follow closely — makes a shallow angle to the western horizon after sunset in early autumn from mid-northern latitudes. Venus’ elongation from the Sun thus translates more into distance along the horizon than altitude above it. The ecliptic’s angle steepens sharply in late autumn, however, more than offsetting the planet’s dwindling elongation.

On November 1, Venus stands 11° high an hour after sunset; by the 30th, it is 15° high. The planet brightens during November, too, from magnitude –4.5 to –4.8, so it grows even more prominent.

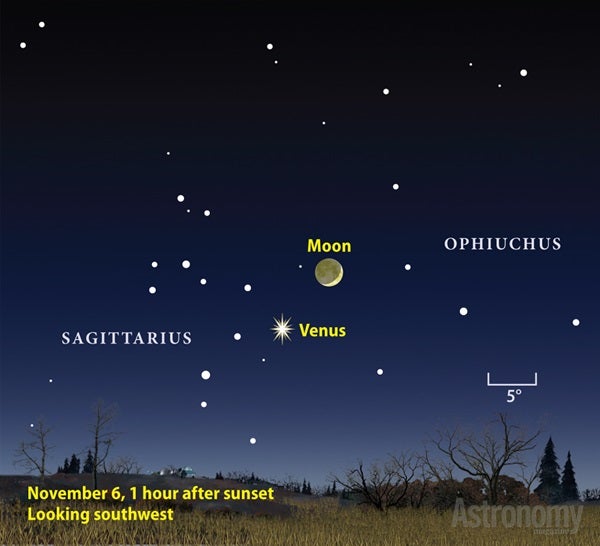

Venus spends the month among the background stars of Sagittarius. On November 6, a waxing crescent Moon passes 8° north of the planet. Look midway between this attractive pair to find the Lagoon (M8) and Trifid (M20) nebulae. On the 13th, Venus slides 3° south of globular star cluster M22. Binoculars will show these deep-sky objects on haze-free evenings once the sky darkens sufficiently.

Once the evening sky grows completely dark, Neptune makes a tempting target. The distant world then lies due south and nearly halfway from the horizon to the zenith. It lies in the central part of the constellation Aquarius, between the 5th-magnitude stars Sigma (σ) and 38 Aquarii. Neptune glows at magnitude 7.9, however, so you will need to study this region in some detail.

The planet spends all of November on the line joining these two stars, approximately 3° west of Sigma and 2° east of 38. To confirm its identity, view it through a telescope at medium to high magnification. Every star will appear as a point of light, but Neptune will show a blue-gray disk measuring 2.3″ across.

The best time to view Uranus is when it lies highest in the south, around 9 p.m. local time in mid-November. The magnitude 5.8 planet travels slowly westward in a rather barren region along the border between Pisces and Cetus. To find the distant orb, scan 6° southwest of magnitude 4.4 Delta (δ) Piscium with your binoculars. The two brightest objects in this area are Uranus and the equally bright star 44 Psc, which lies some 2° farther from Delta. To confirm your sighting, view the object through a telescope at medium magnification. Uranus will show a 3.6″-diameter disk with a distinct blue-green color.

On mid-November evenings, the familiar shape of Orion the Hunter clears the eastern horizon by around 9 p.m. local time. Jupiter and its host constellation, Gemini the Twins, come to prominence to the left of Orion less than an hour later. The giant planet shines brilliantly at magnitude –2.5, so there’s no mistaking it for any star. On the night of November 21/22, a waning gibbous Moon passes 5° south of Jupiter.

Although it might be tempting to observe Jupiter through a telescope as soon as it rises, better views await once it climbs higher. If you wait until 11 p.m. local time, the planet lies 30° high and should look magnificent. The best views will come when Jupiter passes nearly overhead in the early morning hours.

How many belts and zones do you see in the planet’s atmosphere? Most novices see two dark equatorial belts and a brighter zone between them. But with a bit of practice and patience, observers can discern an entire series of parallel bands. Turbulence at the boundaries between these features shows up as delicate wisps and swirls.

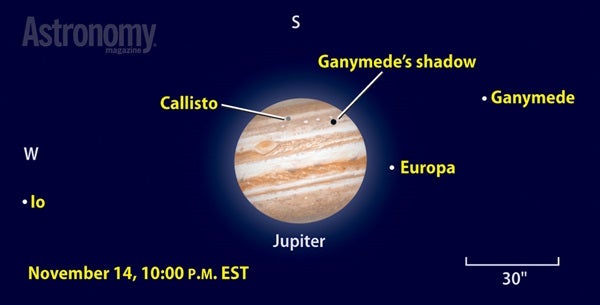

It doesn’t take any experience to enjoy the dance moves of Jupiter’s four bright moons. Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto orbit with clockwork precision and often present intriguing alignments. Some of the best occur when a moon passes in front of Jupiter and casts its shadow onto the planet’s cloud tops. With opposition and peak visibility now two months away, the geometry of the Sun, Earth, and Jupiter causes a satellite’s shadow to transit Jupiter well before the satellite itself.

One of the best events this month favors observers east of the Rockies on the night of November 14/15. As soon as Jupiter rises, point your telescope at the planet’s disk and look for the obvious contrast between Ganymede’s black shadow and Callisto’s grayish disk. Callisto remains silhouetted against the jovian clouds until 11:32 p.m. EST, while Ganymede’s shadow lingers for nearly an hour longer (until 12:25 a.m. EST). Although Ganymede itself lies east of Jupiter during these proceedings, the solar system’s largest moon executes its own three-hour transit starting at 1:42 a.m. EST.

Jupiter stands out during November because it’s so bright. Mars stakes its claim to distinction through its color. The Red Planet’s obvious ruddy glow clears the eastern horizon by 1:30 a.m. local time in mid-November. Shining at magnitude 1.4, it appears bright but not unusually so — a dozen or more stars exceed its intensity these November nights.

Mars begins the month in the constellation Leo the Lion, roughly midway between Regulus and Denebola and just 2.5° south of the bright spiral galaxy M96. Its eastward motion relative to the starry backdrop carries it into Virgo the Maiden on the 25th. Mars remains on the far side of the solar system from Earth and thus appears small (5″ across) and featureless through a telescope.

Mercury passes between Earth and the Sun on November 1 and then quickly climbs into view before dawn. At greatest western elongation on the 17th, it stands 10° high in the east-southeast 45 minutes before sunrise. The innermost planet then shines at magnitude –0.6, so it stands out against the twilight sky.

The inner planet’s relatively high altitude and brightness makes this its finest morning appearance of the year. If you can tear yourself away from Comet ISON long enough to aim your telescope at the planet, you will see a disk that is 7″ in diameter and about 60 percent lit.

Mercury points the way to Saturn on November 25 and 26, when the inner planet lies less than 1° from the ringed world. On the 25th, Mercury appears higher than its companion. The two switch positions the following morning. If you want to observe Saturn through a telescope, wait until it climbs higher in next month’s sky.

Residents along North America’s East Coast can witness a partial solar eclipse as the Sun rises November 3. From Boston, the Moon covers 63 percent of the Sun’s diameter as the pair rises. In Miami, our satellite hides 48 percent of the Sun from view. If you watch the partial eclipse, be sure to look through a safe solar filter.

By the afternoon of the 3rd, the Moon’s shadow sweeps across equatorial Africa. People situated along the narrow path of totality will see the Sun’s disk disappear behind the Moon and usher in one of nature’s finest spectacles.

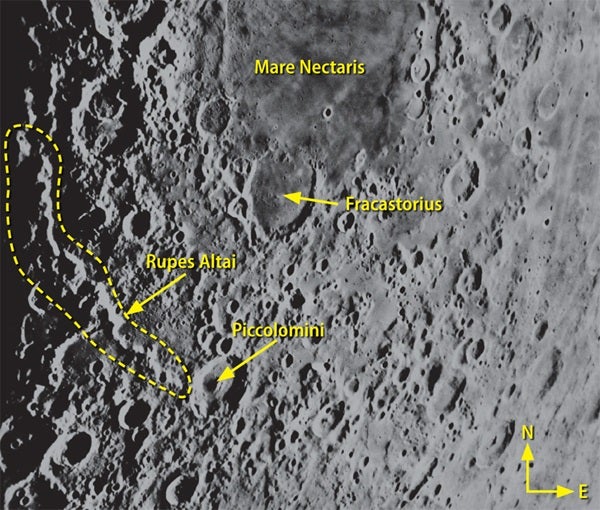

Although it might not seem so at times, there’s more to lunar history than fresh impacts creating new craters and erasing older ones. The massive impact that carved out Mare Nectaris (Sea of Nectar) about 4 billion years ago affected the face of cratering history for millions of years to come. This mare lies just south of the lunar equator and becomes fully illuminated November 8, a day before First Quarter phase.

View this area through your telescope, and a bright white arc will catch your eye. Rupes Altai (Altai Scarp) appears to be centered perfectly on Nectaris, and that’s no accident. This scarp is a remnant of the fourth rim of the Nectaris multiring basin.

The younger crater Piccolomini dangles on the end of the scarp like an earring. This crater spans 55 miles and sports a complex central peak. Examine Piccolomini’s walls, and you’ll see that lots of debris has slumped into the cavity, mimicking the effect you get by digging a hole in wet sand. The crater’s south side has much more material thanks to the unstable terrain generated by the scarp’s formation.

To the north of Piccolomini lies Fracastorius, a crater of intermediate age that’s missing its northern rim. Like water, molten lava finds its own level, so it’s easy to see that Fracastorius tilts down to the north. Lunar geologists have deduced that before this final flood, a smaller surge of lava rose up through cracks in Nectaris’ floor and then solidified, sinking the central part and causing the surrounding terrain to tilt down toward the sea’s middle. By the way, Fracastorius did not get its name because the crater appears fractured. Instead, it honors the 16th-century Italian astronomer Girolamo Fracastoro.

If you view on November 7, you can watch the peaks of Rupes Altai and Piccolomini pop into view one by one as the evening progresses. With the Sun rising slowly over this lunar terrain, high points to the west and lower points to the east light up with each passing hour.

The annual Leonid meteor shower peaks before dawn November 17. In a normal year, skygazers can expect to see up to 15 meteors per hour under a clear, dark sky. Unfortunately, 2013 delivers little darkness because the Moon is Full the same morning.

Your best bet is to observe in the hour before dawn and position yourself so trees or buildings block the Moon. One favorable note: Leonid meteors hit Earth’s atmosphere at the breakneck speed of 44 miles per second, so they produce more fireballs than most meteor showers.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Venus (southwest) |

Jupiter (east) |

Mercury (east) |

| Uranus (southeast) |

Uranus (southwest) |

Mars (southeast) |

| Neptune (south) |

Neptune (west) |

Jupiter (southwest) |

| Saturn (southeast) |

||

Before ISON peaks at the close of November, rise early and enjoy the pre-show during the month’s first half. Observers normally would consider themselves lucky to see one nice binocular comet a year, and we reached that quota in the spring with PANSTARRS (C/2011 L4).

But now we have a simultaneous pair. Periodic comet 2P/Encke hangs low in the east two hours before sunrise a few binocular fields from Comet ISON (C/2012 S1). Both should brighten from 7th to 5th magnitude during November’s first half, bringing them within easy range of binoculars from the country or a 4-inch scope from the suburbs.

Nice comets repay the effort of driving to a dark site, with their dusty tails appearing much longer and wider. Encke should show a fairly bright central core with a narrow fan extending westward. At 100x, its southern flank will be sharper thanks to the confining actions of the solar wind and radiation pressure. In contrast, ISON’s dust tail should be broad because we are viewing it almost from the side.

For visual observers, mid-November will be it for this apparition of Encke. Moonlight hits the morning sky thereafter, and the comet descends into an increasingly bright dawn sky. Its journey outbound from the Sun will be lost in our star’s glare. Still, imagers likely will keep tracking this dirty snowball as a bonus while documenting ISON on its rise to fame.

Viewing ISON during daylight around the time of the comet’s November 28 perihelion will be a thrill but also extremely dangerous, with the threat of accidental blindness and equipment damage. Only viewers in the Northern Hemisphere should attempt this observation. What you need to do is set up in the shadow of a building with a horizontal roofline running east-west. Do this within a half-hour of local noon, when the Sun travels a nearly horizontal path in the sky. Then scan just above the Sun’s blocked position. If ISON brightens well beyond Venus’ typical magnitude –4, you might just glimpse it.

MASSALIA HOOFS IT BENEATH THE RAM

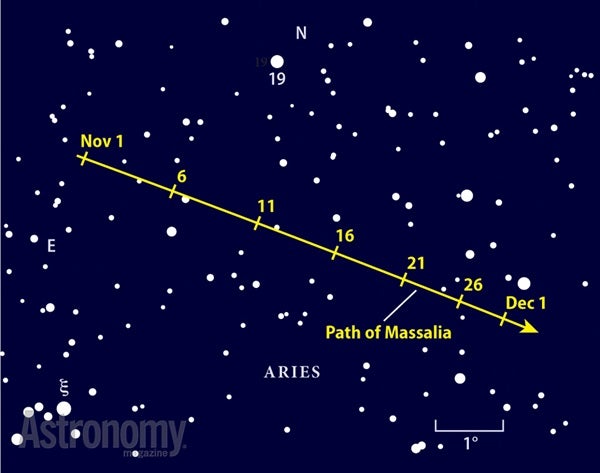

As Aries the Ram climbs high in the southeast during mid-evening, your telescope can reveal the asteroid 20 Massalia hiding in its fleece. From the suburbs, the celestial Ram’s three-star pattern looks like a golf club or hockey stick, but a bit more light pollution or haze reduces it to a wide pair. On your path to our quarry, stop for a couple of minutes to look at the Ram’s fainter third star, Gamma (γ) Arietis. This classic double star looks like a distant car’s headlights when viewed at magnifications of 100x or more.

Glowing at 9th magnitude, Massalia is a reasonable target for a 6-inch scope from the city or a 3-incher under a darker sky. You’ll have to take some care hopping across the open pasture from Aries’ brightest stars to the main-belt asteroid. Massalia lies nearly 10° south of the stars, twice the gap between the handle and tip of the stick pattern. It’s a more comfortable 2° hop from the 6th-magnitude star 19 Arietis.

Use the finder chart to triangulate your way to the right area. Then make a quick sketch of the eyepiece view showing a half-dozen stars. Note which dot you think is the asteroid, and return a night or two later to confirm that it has moved. That’s basically the method Jean Chacornac and Antonin de Gasparis used when they independently discovered Massalia in September 1852.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.