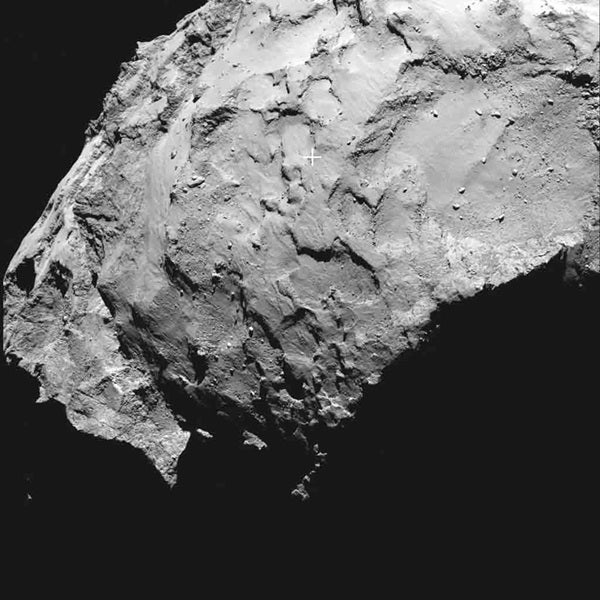

Site J is on the “head” of the comet, an irregular-shaped world that is just over 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) across at its widest point. The decision to select Site J as the primary site was unanimous. The backup, Site C, is located on the “body” of the comet.

The 220-pound (100 kilograms) lander is planned to reach the surface November 11, where it will perform in-depth measurements to characterize the nucleus in situ in a totally unprecedented way.

But choosing a suitable landing site has not been an easy task.

“As we have seen from recent close-up images, the comet is a beautiful but dramatic world — it is scientifically exciting, but its shape makes it operationally challenging,” said Stephan Ulamec from the DLR German Aerospace Center in Munich.

“None of the candidate landing sites met all of the operational criteria at the 100 percent level, but Site J is clearly the best solution.”

“We will make the first ever in-situ analysis of a comet at this site, giving us an unparalleled insight into the composition, structure, and evolution of a comet,” said Jean-Pierre Bibring from the IAS in Orsay, France.

“Site J in particular offers us the chance to analyze pristine material, characterize the properties of the nucleus, and study the processes that drive its activity.”

The race to find the landing site could only begin once Rosetta arrived at the comet August 6 when the comet was seen close up for the first time. By August 24, using data collected when Rosetta was still about 60 miles (100km) from the comet, five candidate regions had been identified for further analysis.

Since then, the spacecraft has moved to within 20 miles (30km) of the comet, affording more detailed scientific measurements of the candidate sites. In parallel, the operations and flight dynamics teams have been exploring options for delivering the lander to all five candidate landing sites.

Over the weekend, the Landing Site Selection Group of engineers and scientists from Philae’s Science, Operations, and Navigation Centre at France’s CNES space agency, the Lander Control Centre at DLR, scientists representing the Philae Lander instruments and ESA’s Rosetta team met at CNES, Toulouse, France, met to consider the available data and to choose the primary and backup sites.

A number of critical aspects had to be considered, not least that it had to be possible to identify a safe trajectory for deploying Philae to the surface and that the density of visible hazards in the landing zone should be minimal. Once on the surface, other factors come into play, including the balance of daylight and nighttime hours and the frequency of communications passes with the orbiter.

The descent to the comet is passive, and it is only possible to predict that the landing point will place within a “landing ellipse” typically a few hundred meters in size.

A one square kilometers area was assessed for each candidate site. At Site J, the majority of slopes are less than 30º relative to the local vertical, reducing the chances of Philae toppling over during touchdown. Site J also appears to have relatively few boulders and receives sufficient daily illumination to recharge Philae to continue science operations on the surface beyond the initial battery-powered phase.

Provisional assessment of the trajectory to Site J found that the descent time of Philae to the surface would be about seven hours, a length that does not compromise the on-comet observations by using up too much of the battery during the descent.

Both Sites B and C were considered as the backup, but C was preferred because of a higher illumination profile and fewer boulders. Sites A and I had seemed attractive during first rounds of discussion, but were dismissed at the second round because they did not satisfy a number of the key criteria.

A detailed operational timeline will now be prepared to determine the precise approach trajectory of Rosetta in order to deliver Philae to Site J. The landing must take place before mid-November as the comet is predicted to grow more active as it moves closer to the Sun.

“There’s no time to lose, but now that we’re closer to the comet, continued science and mapping operations will help us improve the analysis of the primary and backup landing sites,” said Andrea Accomazzo from ESA.

“Of course, we cannot predict the activity of the comet between now and landing and on landing day itself. A sudden increase in activity could affect the position of Rosetta in its orbit at the moment of deployment and in turn the exact location where Philae will land, and that’s what makes this a risky operation.”

Once deployed from Rosetta, Philae’s descent will be autonomous, with commands having been prepared by the Lander Control Centre at DLR and uploaded via Rosetta mission control before separation.

During the descent, images will be taken and other observations of the comet’s environment will be made.

Once the lander touches down, at the equivalent of walking pace, it will use harpoons and ice screws to fix it onto the surface. It will then make a 360° panoramic image of the landing site to help determine where and in what orientation it has landed.

The initial science phase will then begin with other instruments analyzing the plasma and magnetic environment and the surface and subsurface temperature. The lander will also drill and collect samples from beneath the surface, delivering them to the onboard laboratory for analysis. The interior structure of the comet will also be explored by sending radio waves through the surface toward Rosetta.

“No one has ever attempted to land on a comet before, so it is a real challenge,” said Fred Jansen from ESA. “The complicated ‘double’ structure of the comet has had a considerable impact on the overall risks related to landing, but they are risks worth taking to have the chance of making the first ever soft landing on a comet.”

The landing date should be confirmed September 26 after further trajectory analysis and the final Go/No Go for a landing at the primary site will follow a comprehensive readiness review October 14.

Comets are time capsules containing primitive material left over from the epoch when the Sun and its planets formed. By studying the gas, dust, and structure of the nucleus and organic materials associated with the comet, via both remote and in situ observations, the Rosetta mission should become the key to unlocking the history and evolution of our solar system as well as answering questions regarding the origin of Earth’s water and perhaps even life.