The $20 million SpaceShipOne is the brainchild of Burt Rutan, head of Scaled Composites. The sole sponsor of the SpaceShipOne program is Paul Allen, philanthropist and co-founder of Microsoft.

Rutan and Allen are competing with 23 other companies for the Ansari X Prize. This $10 million award will go to the first group that privately funds a spacecraft that carries at least three people, reaches an altitude of 62 miles (100 km), returns safely to Earth, and repeats the mission within two weeks. The goal of the X Prize Foundation is to jumpstart the space tourism industry. — Jeremy McGovern

Five years and counting

June 24 will mark the five-year anniversary of NASA’s Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer (FUSE) satellite launch into space. Astronomers use the team of four telescopes aboard the satellite to monitor far-ultraviolet light emitted from objects. FUSE has returned noteworthy findings, such as a peek into the molecular hydrogen of Mars’s atmosphere and the first view of molecular nitrogen outside the solar system.

“The sheer magnitude and amount of scientific work that is being produced using FUSE is beyond even what we had imagined,” says Warren Moos, FUSE’s principal investigator from The Johns Hopkins University. “What has been accomplished is extremely impressive and very satisfying.”

The mission has had its problems, such as in 2001 when two of its reaction wheels broke. Without these, FUSE’s instruments would not operate or maneuver properly. Team members remedied the situation by using the satellite’s computers to serve the function of the missing wheels. — Jeremy McGovern

Cosmic powerhouses dwell in humble homes

Quasars, the most brilliant cosmic fireworks, are capable of emitting more than a trillion times more light than the Sun, from an area not much larger than the solar system. For a long time, astronomers thought that brighter quasars inhabited brighter host galaxies, but new observations from the Gemini Observatory have shown otherwise: Quasars shine from regular, humdrum galaxies, not giant or disrupted ones.

“It’s like finding a Formula One racing car in a suburban garage,” says Scott Croom of the Anglo-Australian Observatory, who led the study. His team examined nine host galaxies, all about 10 billion light-years away, in the infrared, expecting to see abnormal galaxies whose sizes and shapes could lend some clues to the origin of their quasars. The quasars’ pedestrian surroundings, however, gave the scientists quite a shock. Their results were presented at this year’s Gemini Science Conference in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. — Pamela Zerbinos

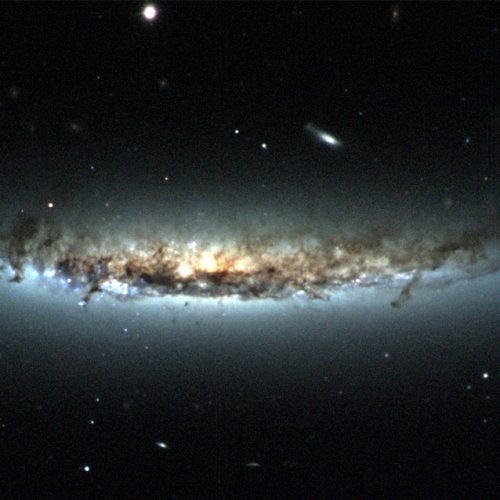

Stripping a spiral

A new three-color composite image of spiral galaxy NGC 4402 shows striking evidence of a galaxy being stripped bare of its star-forming material. NGC 4402 lies about 50 million light-years from Earth and is moving toward the center of the Virgo galaxy cluster. As it falls, it encounters a hot “wind” from the cluster gas, which can reach temperatures of millions of degrees. This hot wind strips away most of the cooler gas and dust of the galaxy, taking with it most of the galaxy’s star-forming ability. “This image clearly shows galactic disruption on a grand scale,” said Hugh Crowl of Yale University, who presented the results at this month’s American Astronomical Society meeting. “It gives us much more confidence that this widely postulated process truly plays a significant role in shaping the evolution of clusters in galaxies.” — Pamela Zerbinos

Pinwheel’s hidden wonders

A new Spitzer Space Telescope image of our neighbor, the Pinwheel Galaxy (M33), reveals dusty red spiral arms studded with bright knots that represent star-forming regions. Because Spitzer sees in the infrared, it can penetrate the clouds of dust that obscure such regions in the visible spectrum, revealing never-before-seen features. A Spitzer team led by Elisha Polomski will study M33 for the 2½ years in hopes of understanding the processes that keep the galaxy going: the circulation of energy and chemical elements to build up, destroy, and re-form stellar building blocks. — Pamela Zerbinos

Darkly illuminating

Most galaxies — including our own Milky Way – are strewn with giant clouds of gas and dust that appear as dark silhouettes against a starry sky. These clouds, known as nebulae, shine only when illuminated by nearby energy sources. Philip Kaaret (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) and colleagues have identified a distant nebula that is illuminated by x-rays from a nearby black hole. The nebula, about 100 light-years wide, lies in the dwarf irregular galaxy Holmberg II, which is some 10 million light-years away. This surprising find, presented by Kaaret at this month’s meeting of the American Astronomical Society, is only the second example of a nebula powered by a black hole. — Pamela Zerbinos

Fixing Hubble by robot

In an address to the American Astronomical Society at its meeting in Denver, NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe announced on June 1 that the agency is requesting proposals for robotic missions to service the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). The proposals are due July 16. According to the agency, any robotic serving mission must, at a minimum, be able to deorbit HST safely. An additional capability — one that’s “highly desirable” in O’Keefe’s words — will be to replace the telescope’s gyroscopes and batteries to extend the telescope’s operating lifetime. Third in priority is to install new instruments that would enhance or extend HST’s capabilities.

At present, HST has four functioning gyros, three of which are used at a time. Steven Beckwith, director of the Space Telescope Science Institute, notes that HST’s operations team has developed ways to achieve somewhat diminished science with HST running on just two gyros. With one working gyro (or none), HST goes into a safe mode that holds its orientation fixed in space, making it easy to dock with. Says Beckwith, “HST in safe mode remains a compliant target” in case a servicing mission is delayed. Engineering projections indicate that by the end of 2006, HST likely will be running with just two gyros, which will drop to one by mid-2007 or thereabouts. (Battery life, while also declining, is believed to be adequate through about 2010.) — Robert Burnham

What did the Big Bang sound like?

It didn’t make a “bang!” — nor did it make a rumble. In fact, the Big Bang was completely silent at first.

Astronomer Mark Whittle (University of Virginia) has reconstructed what the Big Bang would have sounded like. After the initial silence, it was, he says, “a descending scream that built into a deep rasping roar and ended in a deafening hiss.”

Naturally, no human being — nothing living, in fact — existed then or could have survived the explosion to hear what it sounded like. But according to Whittle, the minute fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background radiation amount to frozen sound waves from the Big Bang. These fluctuations were mapped in detail by NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe, which was launched in 2001.

Unfortunately for lovers of celestial music, the harmonic structure of the fluctuations does not produce pure chords as a musical instrument does. Thus, the sound might best be described as grating. It is also overwhelmingly loud. “[It was] about 110 decibels,” Whittle notes, “like a rock concert.”

What about the initial silence? “Before the fluctuations had time to develop, the expansion was so smooth it would not have made any noise at all,” Whittle explains. — Robert Burnham

Speed limit for solar eruptions?

It takes 12 hours for material erupted from the Sun in a solar flare to reach Earth, according to astronomer Nat Gopalswamy (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center) and a team of coworkers. Such eruptions are called coronal mass ejections (CMEs). The researchers studied historical records of solar flares and their aftermaths going back to the first flare identified, by Richard Carrington in 1859.

Coronal mass ejections can be thrown from the Sun at various speeds, but the team’s finding suggests there’s a speed limit built into the process. They think this comes from a natural constraint on the amount of energy that can be stored in the tangled magnetic fields that cause a solar flare.

This finding means that operators have half a day to prepare satellites in Earth orbit, which can have their electronic circuits overwhelmed or destroyed by the arrival of a CME. Also, astronauts in space get the same warning time and can take precautions, such as seeking shelter in parts of the International Space Station where they are surrounded by more shielding. — Robert Burnham

How far the Pleiades

Astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope have resolved a controversy over the distance to the Pleiades, a star cluster in the constellation Taurus and the best known star cluster in the heavens.

Measuring the position of a nearby star six months apart reveals an apparent shift in its position against more distant stars — the basis for astronomy’s most accurate means of determining distance. A team led by David Soderblom of the Space Telescope Science Institute used the Hubble Space Telescope’s Fine Guidance Sensors to measure the shift of three Pleiades stars. The result — a distance of 440 light-years — jibes with recent ground-based measurements but disagrees with results reported from the European Space Agency’s Hipparcos satellite in 1997.

Hipparcos found the Pleiades to be 10 percent closer than previous studies, a discrepancy astronomers have called “one of the more dramatic controversies in modern astrophysics.” If true, it meant that the cluster’s stars were peculiar because they appeared slightly fainter than would similar types of stars placed at the same distance.

“The new Hubble result shows that the measurements made by Hipparcos contain a small, but significant, source of error that requires further exploration,” said Soderblom. He reported his findings at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society being held in Denver, Colorado, this week. — Francis Reddy