Although nothing comes easily for planet observers shortly after sunset, nice views come to those who seek them. Saturn makes its final evening appearance of 2012 during October’s first few days. From mid-northern latitudes on the 1st, the ringed planet lies 5° high in the west-southwest 30 minutes after the Sun goes down. It shines at magnitude 0.7, which makes it tough to see with naked eyes but an easy target through binoculars.

Saturn’s low altitude has a lot to do with solar system geometry. The ecliptic — the Sun’s apparent path across the sky that the planets follow closely — makes a shallow angle to the western horizon on October evenings. So, a planet’s elongation from our star translates more into distance along the horizon and less into elevation.

In the Southern Hemisphere, however, the opposite holds true. The ecliptic currently stands nearly straight up from the western horizon after sunset, so the planets appear much higher. From 30° south latitude, Saturn resides 13° high in the west a half-hour after sundown and remains on view until darkness falls. From both hemispheres, however, the ringed planet disappears quickly. It passes behind the Sun from our perspective October 25 and will return to the morning sky in November (when northerners will have the better view).

Mercury experiences a similar fate. When it reaches greatest elongation October 26, it lies 24° east of the Sun. To those in the north, the planet barely scrapes the horizon, climbing 3° high 30 minutes after sunset. But in the Southern Hemisphere, the 26th marks the peak of Mercury’s best evening appearance of the year. The innermost world stands 17° high a half-hour after sundown and doesn’t set until 90 minutes later. Shining at magnitude –0.2, it appears obvious to anyone who looks.

The planet moves quickly eastward relative to the background stars in October. It begins the month against the backdrop of Libra, enters Scorpius on the 6th, and shifts into Ophiuchus after midmonth. A slender crescent Moon lies near Mars on October 17 and 18.

But the planet’s most intriguing encounter comes when it passes 4° north of the bright star Antares the evening of October 19. Antares’ name derives from Greek words meaning “rival of Ares” (Ares being the Greek equivalent to the Roman god Mars) — a reference to the objects’ similar colors. A view through binoculars lets you compare their ruddy hues. This month, the comparison is easier because both objects shine with nearly the same brightness. Unfortunately, a telescope won’t show any martian detail because the planet spans only 5″.

The solar system’s outermost planets lie higher in the late-evening sky. Neptune stands about 40° above the southern horizon shortly after 9 p.m. local daylight time. Glowing at magnitude 7.9, it’s a good target for those with binoculars. The distant world remains less than 0.5° south of 5th-magnitude 38 Aquarii all month. The star lies near Aquarius’ border with Capricornus and shines 10 times brighter than the planet. A telescope at high magnification on a night with good seeing conditions reveals Neptune’s 2.3″-diameter disk and subtle blue-gray color.

Uranus trails Neptune across the sky. It reaches a peak altitude of about 50° when it lies due south around midnight local daylight time. Glowing at magnitude 5.7, Uranus is easy to see through binoculars and even shows up to naked eyes under a dark sky.

The equally bright star 44 Piscium serves as a guide to the planet. On October 1, Uranus lies 0.3° west-southwest of the star; by month’s end, the gap has grown to 1.5° in the same direction. Both objects reside some 10° east of Pisces’ Circlet asterism. When viewed through a telescope with a moderate- to high-power eyepiece, Uranus’ disk spans 3.7″ and sports a distinctive blue-green hue.

Drama in the jovian cloud tops is a nearly everyday occurrence. High-velocity jet streams create parallel cloud bands that circle the planet. They appear as an alternating series of bright zones and darker belts. Turbulence that exceeds Earth’s most violent storms arises at the boundaries between zones and belts. Features there and elsewhere on the disk can last for days or months. Meanwhile, the Great Red Spot — a high-pressure system with a diameter larger than our entire planet — has existed for centuries.

Jupiter’s apparent equatorial diameter grows from 43″ to 47″ during October as the planet’s distance from Earth shrinks by 33 million miles. Point your scope at the giant world and take time to look carefully. A few minutes of patient viewing will reveal dramatic detail, particularly during moments of steady seeing.

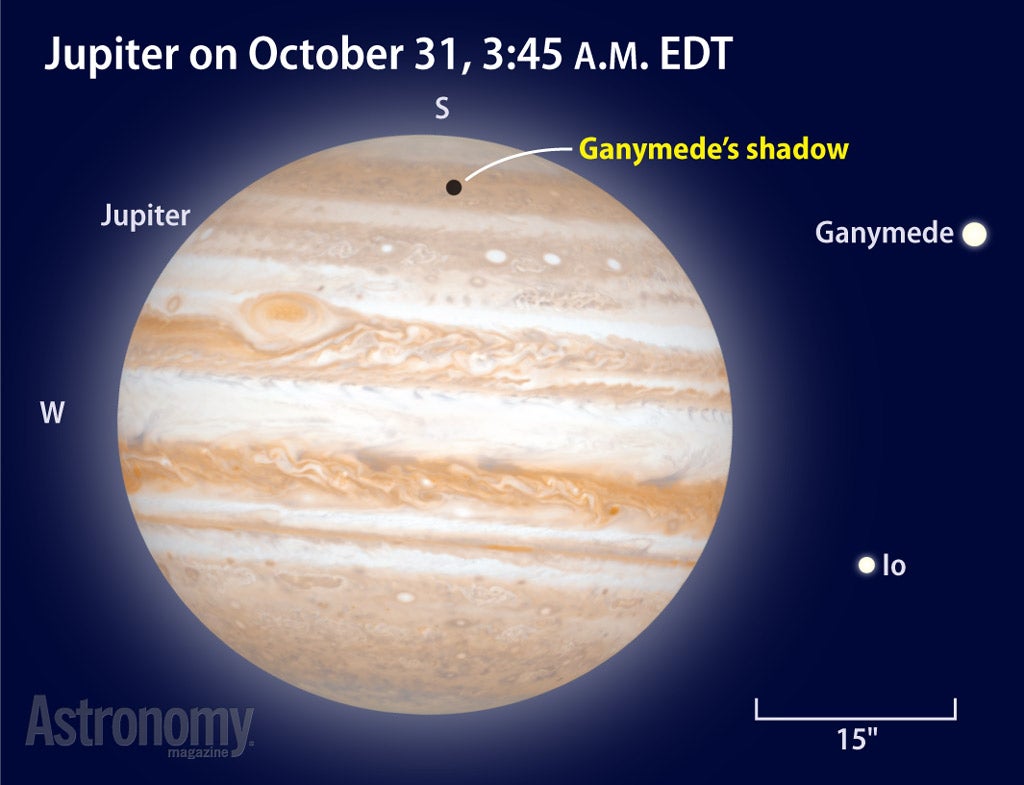

Jupiter’s four major moons prove as dynamic as the planet’s atmosphere. More often than not, all of them are visible against the sky’s dark background, although their constant motion arranges them in different patterns. Occasionally, however, a satellite’s orbit carries it in front of or behind Jupiter. When in front, the moon and its shadow transit the planet’s face; when behind, the planet occults and eclipses the moon.

Perhaps the best show this month occurs the night of October 30/31. At 2:38 a.m. EDT, the large moon’s shadow first touches Jupiter’s limb. For the next two hours, the small black dot traverses the planet’s south polar regions. But observers receive a bonus partway through this transit. Jupiter’s innermost major moon, Io, emerges from behind the planet’s eastern limb at 3:07 a.m. EDT. Approximately 50 minutes later, Io passes 26″ due north of Ganymede, which is approaching Jupiter for its own transit beginning at 5:58 a.m. EDT.

The next night, when ghosts and goblins haunt our neighborhoods on Halloween, Earth’s Moon prowls the night sky in the company of Jupiter. The pair rises between 7 p.m. and 8 p.m. local daylight time and should help light the way for trick-or-treaters. The 31st marks the second time this month that a waning gibbous Moon passes near the giant planet. The two also appear close to each other the night of October 5/6.

As Jupiter climbs high in the south before dawn, an even brighter point of light pokes above the eastern horizon. Venus rises around 3:30 a.m. local daylight time October 1. Leo the Lion’s luminary, Regulus, joins the planet 10 minutes later. Venus shines at magnitude –4.1 — more than 100 times brighter than the magnitude 1.4 star.

The two stand 2° apart that morning, but the gap quickly narrows. Before dawn October 3, Venus passes a mere 7′ (one-quarter of the Full Moon’s diameter) south of Regulus. This is the closest approach of a planet to a 1st-magnitude star during 2012. Both objects will appear in the same field of view through a telescope. The star’s blue-white color should contrast nicely with Venus’ slightly yellowish hue.

The remainder of October finds Venus moving eastward against the background stars. As it crosses southern Leo, the planet passes 3° south of the bright spiral M95 on October 11. This galaxy hosted a supernova (2012aw) in March that peaked at 13th magnitude. The planet crosses into Virgo on the 23rd and skims 0.7° north of 4th-magnitude Beta (β) Virginis on the 26th. As October closes, Venus rises around 4:30 a.m. local daylight time, still some 90 minutes before twilight commences.

Venus’ speedy motion with respect to the background stars contrasts with the relatively minor variations in its telescopic appearance. The planet’s apparent diameter shrinks from 16″ to 13″ in October while its gibbous phase fattens from 71 percent to 81 percent lit. These changes reflect Venus’ increasing distance from Earth and the closer alignment between our two planets and the Sun.

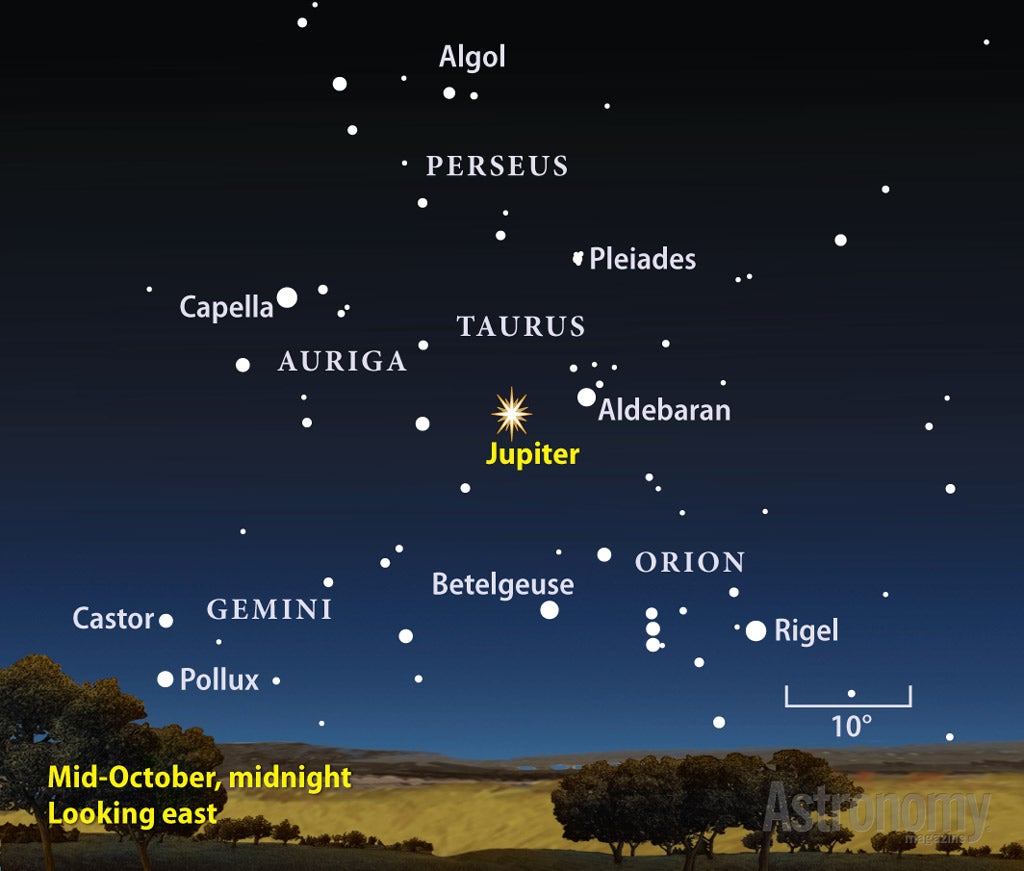

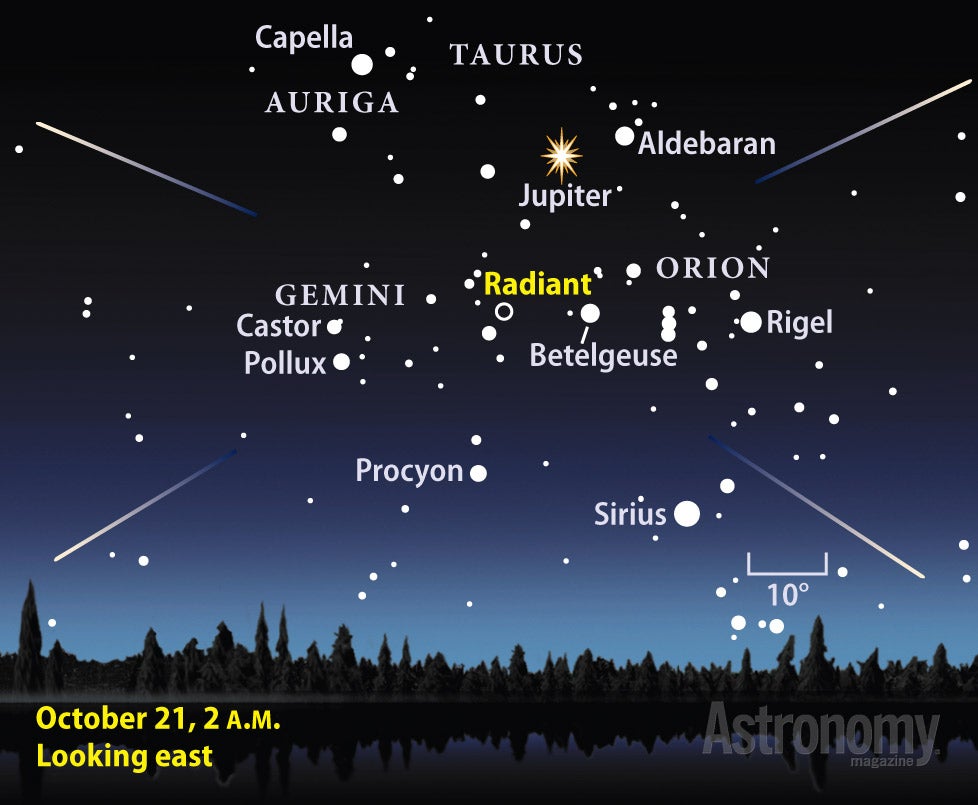

A consistent annual shower could team up with an erratic source of fireballs to deliver a powerful one-two punch for October meteor viewers. First up, the Orionid meteor shower peaks the night of October 20/21. These streaks of light appear to radiate from the constellation Orion the Hunter. A waxing crescent Moon sets around 11 p.m. local daylight time on the 20th, just as Orion rises in the east. This leaves the sky dark during the prime viewing hours before dawn. The Orionids typically produce up to 25 meteors per hour at their peak.

The wild card is a possible return of the Taurid “swarm,” a group of relatively large particles that produced an outburst of fireballs (meteors brighter than Venus) in 1951. Some astronomers predict this swarm should return every 61 years, and 2012 has arrived. Bright meteors could appear from about October 28 to November 11. Although Full Moon comes October 29, moonlight can’t hide a fireball. Meteor observing never offers guarantees, but only those outside can hope to see a potentially memorable display.

The effects of the September 29 Harvest Moon linger into the first days of October. The waning gibbous Moon rises about 30 minutes later each evening compared with a more typical 50-minute delay the rest of the year. So, observers get a splendid opportunity to see sunset illumination on Luna without having to stay up late. And just like in your own neighborhood, where the play of light and shadows looks different at sunrise than at sunset, the Moon looks different under reversed lighting.

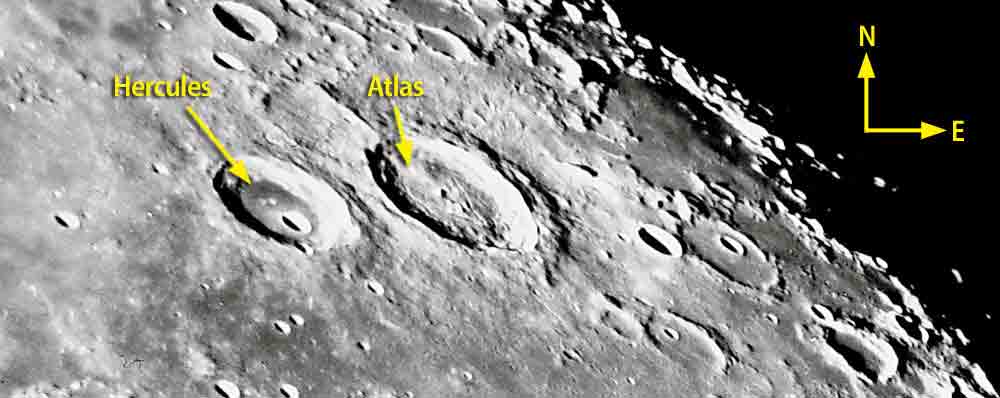

Point your telescope to the Moon’s northeastern quadrant the evening of October 2, and you’ll see two neatly paired craters representing the muscle men of mythology: Atlas and Hercules. Hercules sports a dark lava-filled floor punctured by a modest-sized crater (Hercules G) with sharp edges. The older Atlas has a wrinkled floor and a jumble of central peaks typical of larger craters. As the Sun sets over the region October 3, those peaks drop into darkness and Hercules’ inner crater succumbs to the approaching shadows.

A fortnight later, the crater pair emerges into sunlight with the shadows facing the opposite direction. The Sun lights the craters’ outer rims on the eastern side and their inner crater walls on the west. The crater inside Hercules is lost in shadow October 19 but is easy to see on the 20th.

| When to view the planets | ||

| EVENING SKY | MIDNIGHT | MORNING SKY |

| Mercury (southwest) | Jupiter (east) | Venus (east) |

| Mars (southwest) | Uranus (south) | Jupiter (southwest) |

| Saturn (west) | Neptune (southwest) | |

| Uranus (east) | ||

| Neptune (southeast) | ||

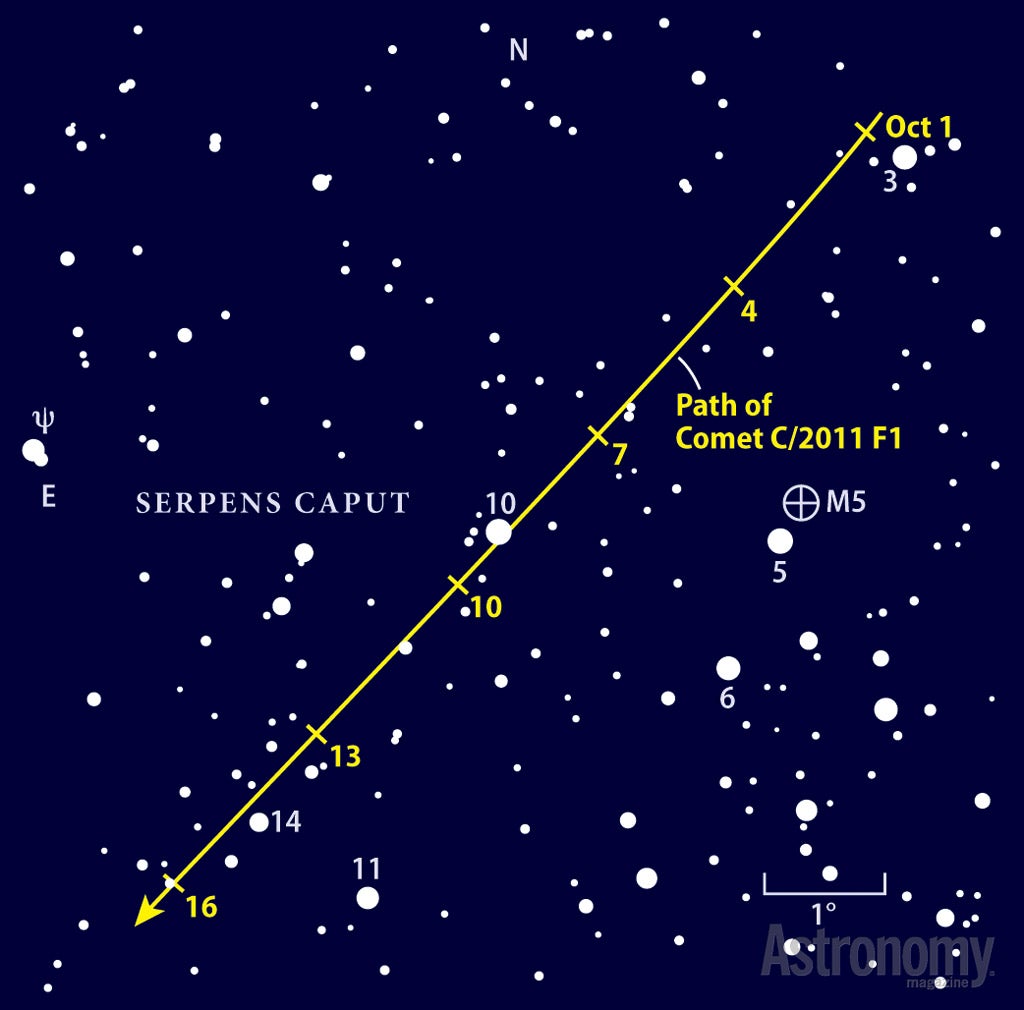

You can hone your observing skills by comparing a comet to a globular star cluster. When viewed through a telescope, the two types of objects often share similar characteristics: They appear round, grow brighter toward the middle, and possess diffuse edges. This month offers a prime comparison when Comet C/2011 F1 (LINEAR) passes the magnificent globular M5 in Serpens.

The pair lies low in the west as darkness falls during October’s first half. The comet begins the month just 0.4° northeast of the 5th-magnitude star 3 Serpentis. (It passes closer to a similarly bright star, 10 Serpentis, on the 9th.) But the best nights to observe are between the 4th and 8th when LINEAR lies within 2° of M5. Plan to view under a dark sky to make out the comet’s 10th-magnitude glow.

It requires only a gentle nudge to switch the view from comet to cluster. Although LINEAR should look mostly circular, you might see a short tail pointing eastward. The first thing you’ll notice about M5 is how much brighter it shines than the comet. The combined output of the globular’s 100,000 suns equals that of a magnitude 5.7 star, which is dozens of times brighter than LINEAR.

As you scrutinize the pair, take a minute to ponder how far away they are. The comet currently lies about 265 million miles from Earth. Put another way, LINEAR’s light takes about 24 minutes to reach us. M5, on the other hand, lies at a distance of 25,000 light-years, or more than 500 million times farther away.

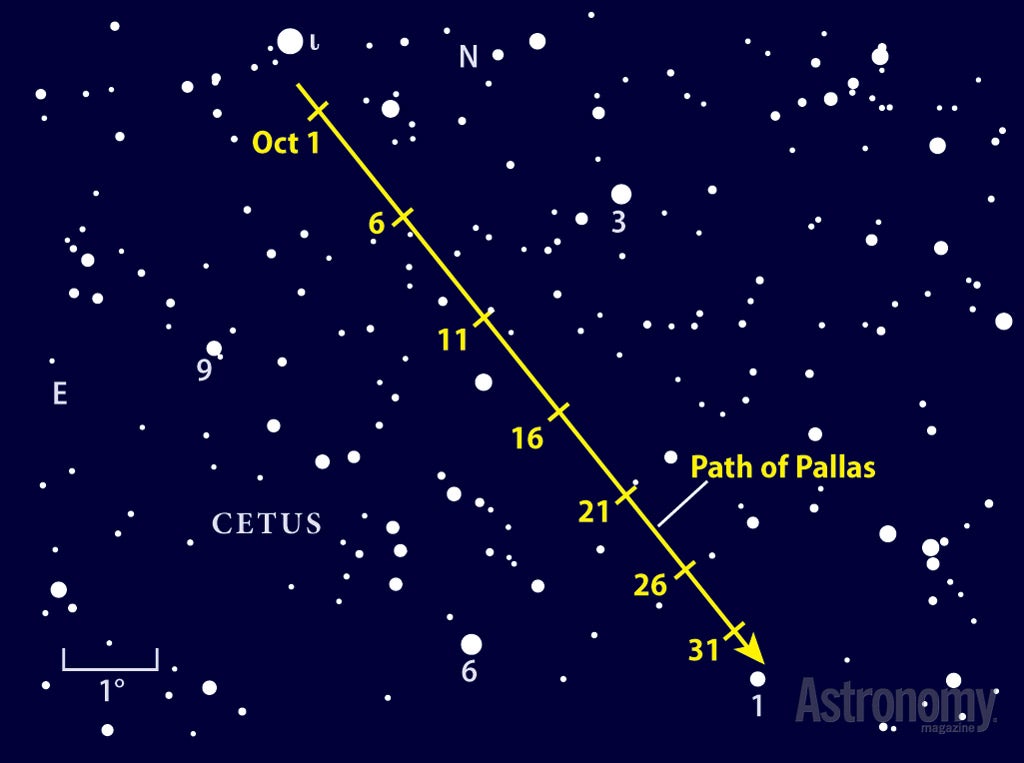

Asteroid hunters receive a nice change of pace this month when a relatively bright target moves across a sparse star field. Asteroid 2 Pallas glows at magnitude 8.3 in early October and rides the sky in western Cetus, just beyond the Whale’s tail and well away from the Milky Way’s crowded background. You should be able to spot this space rock through any telescope. Wait until midevening when it lies about one-third of the way up in the southeastern sky.

Pallas begins the month approximately 1° south-southwest of magnitude 3.5 Iota (ι) Ceti (Iota sits 11° north-northwest of 2nd-magnitude Beta [β] Ceti). Around October 4 and again from the 16th to the 19th, the asteroid sits practically alone in the eyepiece when viewed through a 4-inch scope from the suburbs.

Pallas spans 325 miles, which makes it a bit larger than 4 Vesta. Pallas appears dimmer than its cousin because its surface reflects less than half as much sunlight. German astronomer Heinrich Olbers discovered Pallas in March 1802. Olbers’ main claim to fame comes from posing a famous paradox: “Why is the sky dark at night?”

Martin Ratcliffe provides professional planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. Alister Ling is a meterologist for Environment Canada.