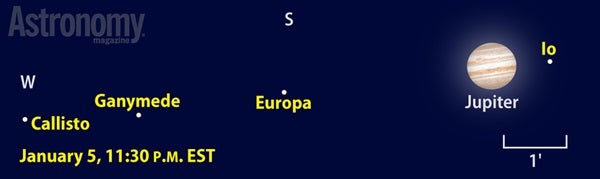

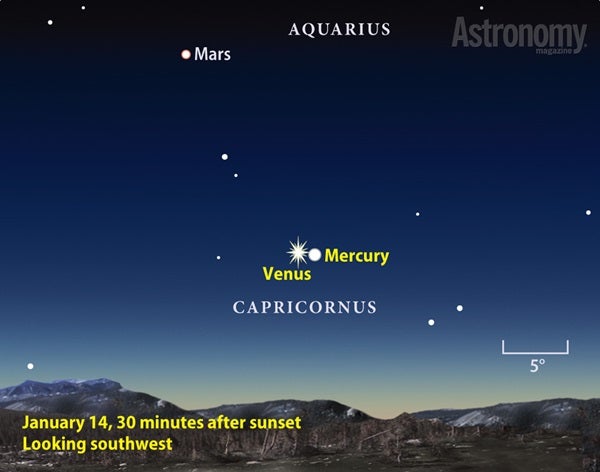

Our tour of January’s night sky begins low in the southwest after sunset. Venus and Mercury spend the month’s first three weeks within the field of view of 7×50 binoculars. Venus shines brilliantly at magnitude –3.9 and shows up easily in bright twilight; it serves as a guide for finding Mercury during this period.

On January 1, Mercury lies 3° to Venus’ lower right and some 4° above the horizon 30 minutes after sunset for people at mid-northern latitudes. The innermost planet glows at magnitude –0.8, just 6 percent as bright as its neighbor but still good enough to show up in twilight.

By January 10, Mercury’s altitude a half-hour after sundown has more than doubled (to 9°), and it appears conspicuous only 0.6° due west of Venus. This marks their closest approach of 2015, though the two technically don’t experience a conjunction because they never have the same right ascension. The planets remain within 1° of each other through the 13th.

As Mercury swings away from Venus, the innermost planet reaches greatest elongation January 14. It then lies 19° east of the Sun and hangs 10° above the horizon a half-hour after sunset. The planet remains bright (magnitude –0.7) and distinct in twilight. A few days after greatest elongation, Mercury starts to fade and sink lower, and it passes between the Sun and Earth on the 30th. But it has one last hurrah before departing. As darkness falls January 21, the waxing crescent Moon stands 5.5° above Mercury (now at magnitude 0.6) and the same distance to Venus’ right.

As twilight deepens, a distinctly orange-colored point of light appears above Mercury and Venus. You can’t miss Mars — at magnitude 1.1, it shines brighter than any nearby star. The Red Planet lies 20° high in the southwest an hour after sunset throughout January. A telescopic view proves disappointing, however, because Mars’ disk measures less than 5″ across and shows no detail.

Mars maintains its altitude because it races eastward in front of the stars of Capricornus and Aquarius at nearly the same rate as the Sun traverses Sagittarius and western Capricornus. The planet’s motion carries it just 0.2° south of Neptune on January 19. Use a telescope to view the two worlds together and compare Mars’ ruddy glow to Neptune’s blue-gray hue. Neptune shines at magnitude 7.9 and appears about half of Mars’ diameter despite lying some 15 times farther away.

Neptune has a second close encounter this month, though it will be harder to view. On January 31, Venus approaches within 1.2° of the distant world. The pair stands only 10° high an hour after sunset, however, and it will be difficult to see Neptune against the twilight.

Uranus rides high in the southwest after darkness falls this month. On the 15th, it appears halfway to the zenith at 7 p.m. local time and sets after 11 p.m. The planet glows at magnitude 5.8, so binoculars will let you track it down. Uranus lies in the company of three similarly bright stars 3.2° due south of magnitude 4.4 Delta (δ) Piscium. A telescope will confirm a sighting of the ice giant by revealing its 3.5″-diameter disk and blue-green color.

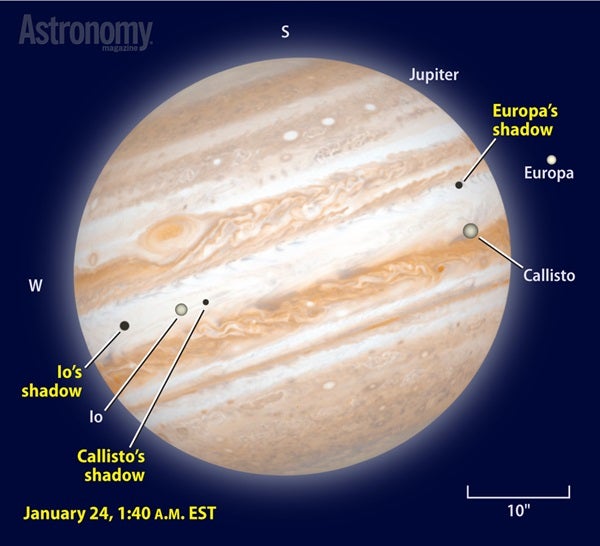

The Sun’s largest planet never disappoints those who view it through a telescope. Jupiter’s disk grows from 43.4″ to 45.3″ across during January, ending the month just 0.1″ short of its peak at opposition in early February. The planet’s dynamic atmosphere changes appearance hour by hour as its rapid spin carries new details into view.

The most obvious features are two dark belts straddling a brighter zone that coincides with the gas giant’s equator. On nights when Earth’s atmosphere is steady (you’ll know because stars won’t twinkle much), a series of dark belts and bright zones comes into view. Also check out the Great Red Spot if it happens to be on the Earth-facing hemisphere. This giant storm has shrunk noticeably in recent years and is now smaller than at any time since scientists started measuring it — though it’s still wider than Earth.

If details appear fuzzy, wait until Jupiter climbs higher in late evening. The greater altitude means its light travels through less of Earth’s turbulent atmosphere. The planet appears highest in the south after midnight.

Once you’ve soaked up photons from Jupiter itself, turn your attention to the planet’s four large moons. These worlds show up easily through small telescopes, and watching them change positions as they orbit the planet provides many thrills. For the first time in five years, the satellites’ orbital plane now tilts nearly edge-on to the Sun and Earth. This ushers in a series of “mutual events,” where one moon may pass in front of another (an occultation) or enter another’s shadow (an eclipse). Dozens of such events occur this month. In addition, each satellite traverses Jupiter’s disk and casts its shadow onto the jovian cloud tops once every orbit.

The moons themselves appear silhouetted against Jupiter’s disk from 11:54 p.m. to 2:12 a.m. (Io), 1:19 to 6:02 a.m. (Callisto), and 2:08 to 5:02 a.m. (Europa). That leaves a brief four-minute interval (2:08 to 2:12 a.m.) when the three moons are simultaneously in transit, though Io and Europa are on the planet’s limb.

The night’s other impressive event comes when Io passes into Callisto’s shadow. The eclipse begins at 12:41 a.m. and concludes 18 minutes later. Observers should notice Io dimming, particularly near the event’s middle. The mutual eclipse offers a tasty morsel in a smorgasbord of events Jupiter viewers won’t soon forget.

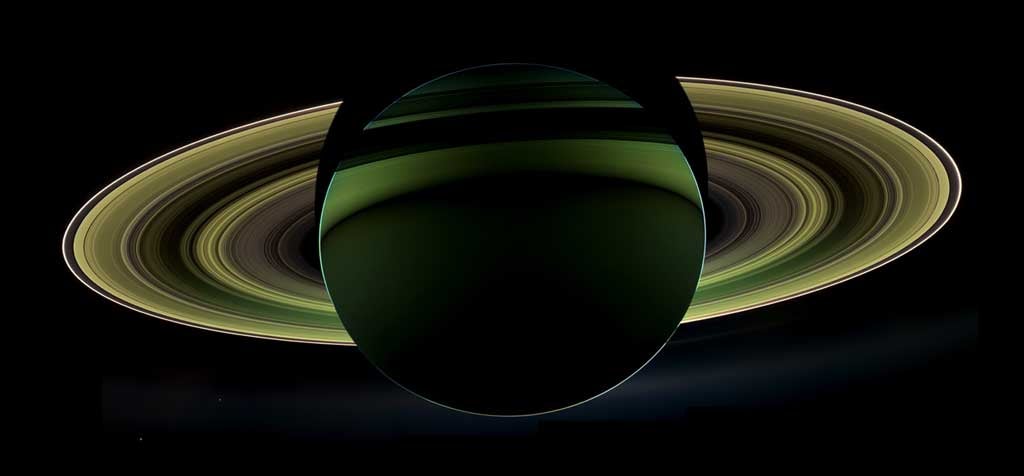

Although Saturn passed behind the Sun from our perspective in November, it quickly returns to prominence before dawn. The ringed planet rises by 4:30 a.m. local time January 1 and about two hours earlier by the 31st. A slender crescent Moon makes a lovely pair with Saturn when it passes 2° north of the planet January 16. One day later, Saturn crosses the border from Libra into Scorpius.

The ringed world shines at magnitude 0.6 and appears slightly yellowish. It contrasts nicely with the ruddy magnitude 1.1 glow of Antares, the Scorpion’s brightest star, which lies 10° below it. When viewed through a telescope, Saturn’s disk spans 16″ and

its rings extend to 36″.

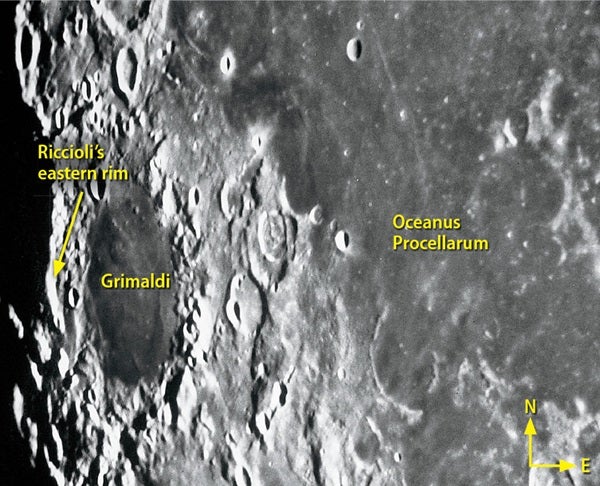

The large impact crater Grimaldi stands out as a dark lava-filled basin near the Moon’s western limb just beyond the edge of the giant mare known as Oceanus Procellarum (Ocean of Storms). The first rays of sunlight spread over Grimaldi the evening of January 3.

The crater’s highly battered rim appears quite ragged thanks to the pummeling it received over many eons by smaller projectiles. Although the rim doesn’t rise far above its surroundings, the low Sun angle causes it to cast long shadows onto the crater’s smooth floor. At Full Moon the next evening (January 4), these shadows have completely disappeared. Many other interesting sights have appeared west of Grimaldi, however, notably the equally large and battered crater Riccioli. This feature’s floor appears much rougher than its neighbor’s because the lava that flooded Oceanus Procellarum and Grimaldi didn’t flow that far.

If you spend some time viewing Grimaldi, you’ll notice that the seemingly monotonous gray of its floor is not uniform. Also note a couple of indistinct rays — lighter rock ejected during relatively recent major impacts — in the crater’s northern half.

To make viewing the nearly Full Moon easier on your eyes, use a dark filter on the eyepiece to reduce the brightness. Alternatively, you can crank up the telescope’s power to capture less surface area.

You can see Grimaldi in a totally different light on the morning of January 17 when the Moon is a gorgeous waning crescent. While earthshine bathes the rest of Luna’s face, Grimaldi appears conspicuous as a sharply defined dark ellipse. Notice how much farther from the limb it lies than it did on the 3rd when it was tucked against the edge. This so-called libration, which lets us see a bit onto the Moon’s farside, occurs because our satellite’s rotation on its axis is slightly out of sync with its orbit around Earth.

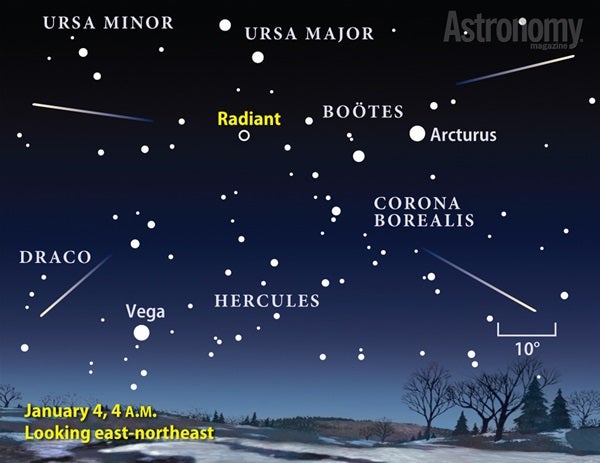

FULL MOON HEADACHES FOR THE QUADRANTIDS

One of the year’s most prolific meteor showers peaks the night of January 3/4. The Quadrantids can produce 120 meteors per hour at their best, but “best” implies viewing under a dark sky with the radiant — the point in northern Boötes from which the meteors appear to originate — nearly overhead. Unfortunately, Full Moon arrives a day after the peak, so dark skies will be impossible to find.

Your best bet is to observe in the hour before dawn breaks. Pick a spot where you can hide the Moon, which hangs low in the west, behind some buildings or trees. The show won’t be great, but you still could see a dozen or two meteors per hour.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Mercury (southwest) |

Jupiter (southeast) |

Jupiter (west) |

| Venus (southwest) |

Saturn (southeast) |

|

| Mars (southwest) |

|

|

| Uranus (south) |

|

|

| Neptune (southwest) | |

|

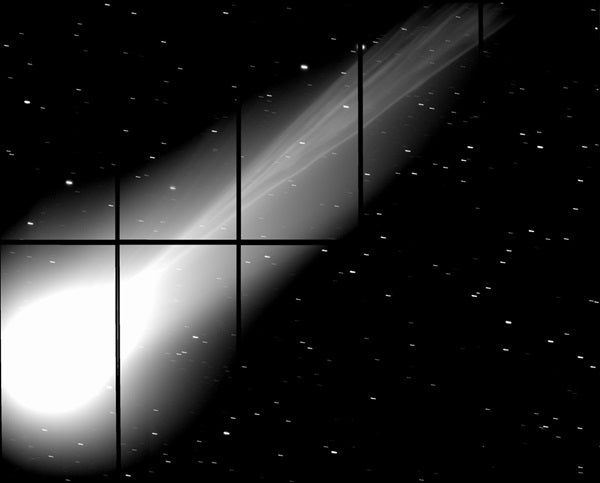

Although spectacular comets have been rare recently, a steady stream of more modest ones has kept our observing juices flowing. Case in point: Comet Lovejoy (C/2014 Q2), which will be nicely placed for evening viewing in January. Lovejoy bolts out from under Lepus the Hare in early January and arrives near the foot of Andromeda the Princess by month’s end. Astronomers predict the comet will glow around 8th magnitude, which would make it difficult to spot from a city. If you head to a dark-sky site, however, a 3- or 4-inch telescope will show it easily.

Lovejoy makes its closest approach to Earth (some 44 million miles away) in early January, and the result is that it races across our sky. The comet covers 3° per day at its peak. This means it will move noticeably in a single observing session.

Amateur astronomer Terry Lovejoy discovered this object August 17, 2014, from Brisbane, Australia. Comets that first light up the deep southern sky tend to have orbits inclined steeply to the solar system’s plane, a characteristic that often carries them well north after they wheel around the Sun. That’s the case with C/2014 Q2 — Lovejoy’s fifth discovery — as it was with his fourth, C/2013 R1. Both the latter comet and Lovejoy’s most famous find, sungrazer C/2011 W3, reached naked-eye visibility. Although this latest Comet Lovejoy won’t be as bright, it still will be fun to follow.

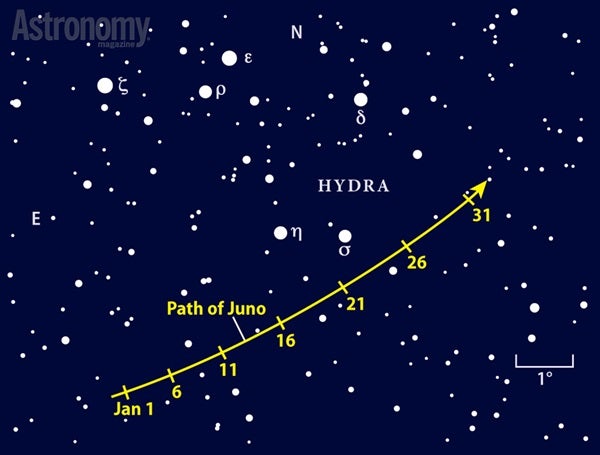

Newcomers to the art of asteroid tracking will be happy to add 3 Juno to their catches. Although it was the third asteroid discovered, it doesn’t often glow brightly enough to be our monthly pick of the litter.

Juno reaches opposition and peak visibility January 29, but it remains an 8th-magnitude object all month. The asteroid rises in early evening following the bright stars of winter. Sirius appears on the right, Jupiter on the left, and the head of Hydra is in between. Juno resides within a few degrees of the head throughout January. The asteroid could pass incognito among the stars in this region, so use the chart below to zero in on its position. You should be able to identify it directly. If not, make a sketch of the four brightest stars in the field and come back a night or two later. The object that moved is Juno.

Astronomers number asteroids by the order of their discovery. Naturally, the brightest ones showed up first. So why isn’t Juno bright every year like 1 Ceres and 4 Vesta? Juno has a fairly eccentric (oval-shaped) orbit, so it spends more of its time far from the Sun. It’s also the smallest of the first four asteroids found, spanning just 170 miles. German astronomer Karl Harding discovered Juno on September 1, 1804, when it happened to be near its closest.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.