Throughout recorded history, Fomalhaut’s main claim to fame has been its rank as the sky’s most isolated 1st-magnitude star. The luminary of Piscis Austrinus the Southern Fish stands alone on autumn evenings, a beacon in the southern sky amidst a smattering of less impressive suns.

Then, 40 years ago, astronomers discovered excess infrared radiation pouring from the star. As scientists pointed ever-more-powerful telescopes in its direction, a picture emerged of an otherwise normal sun surrounded by a disk of warm dust.

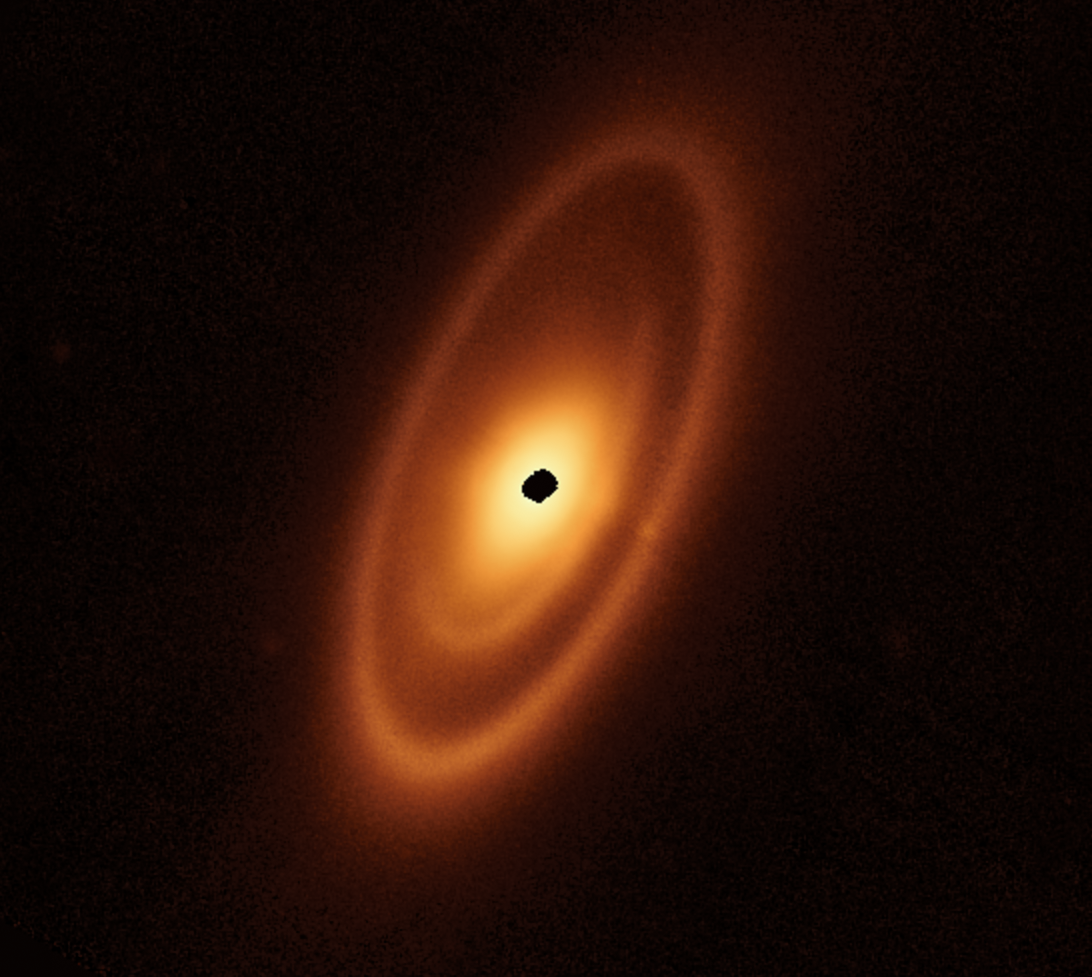

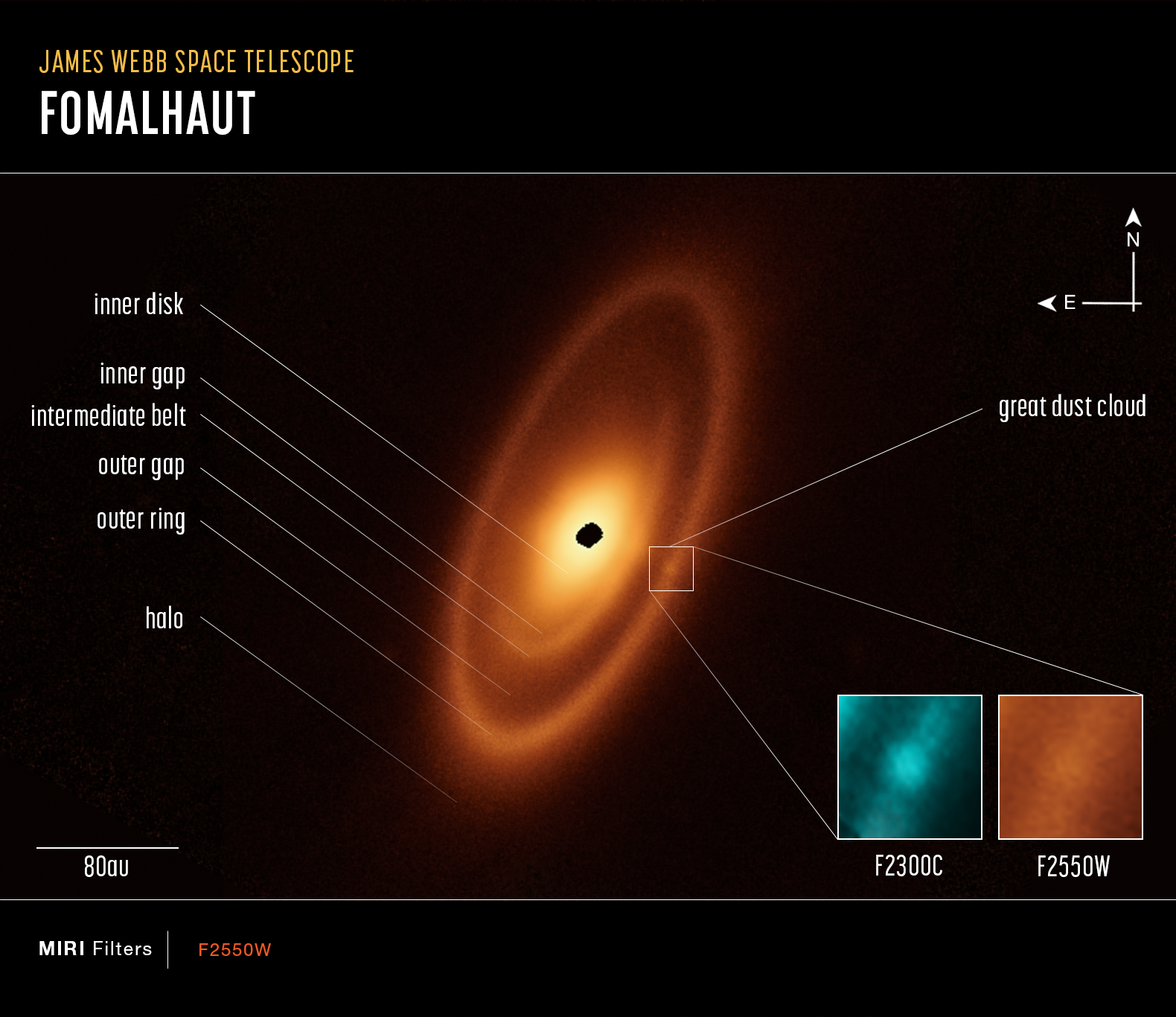

Now, researchers have targeted this nearby star with their latest and greatest infrared instrument — the James Webb Space Telescope. JWST’s images found not one but three nested belts of warm dust surrounding Fomalhaut, the inner two of which had never been seen before. The findings strongly suggest that planets shape the debris disk.

A ringing discovery

The modern story of Fomalhaut begins in 1983. That’s when NASA’s Infrared Astronomical Satellite conducted an all-sky survey for sources of infrared radiation. No one expected to see much coming from relatively hot stars like Fomalhaut. But there it was: A strong signal that could only mean warm dust, likely in a debris disk formed as asteroids and comets left over from the formation of planets collided and got ground into finer particles.

In the decades since, astronomers examined Fomalhaut across the electromagnetic spectrum, from optical to infrared and radio. The observations revealed a narrow ring located between 136 and 150 astronomical units from the star (1 astronomical unit, or AU, equals 93 million miles [150 million kilometers]).

A modern view

That’s where JWST comes in. With its infrared sensitivity fine-tuned to emission from warm dust and its giant 6.5-meter mirror to resolve fine detail, the space telescope proved the perfect instrument for exposing the structure of Fomalhaut’s debris disk.

The observations reveal that the previously seen narrow ring lies outside two smaller belts closer to the star. In many ways it mimics the structure in our own solar system. The outer ring resembles our Kuiper Belt, which starts just outside Neptune’s orbit at 30 AU and extends out to 55 AU. Fomalhaut’s analog stretches nearly three times as far. Neptune sculpts the inner edge of the Kuiper Belt — could an unseen planet perform the same task at Fomalhaut? A large dust cloud resides in this ring and a faint halo lies outside it.

The interior belts are a revelation, never glimpsed before these JWST observations. The inner disk appears somewhat similar to our asteroid belt, though Fomalhaut’s again extends much farther, from about 10 AU to 73 AU. (Our main belt runs from 2.1 to 3.3 AU and Jupiter shepherds its outer edge.)

Beyond this is where it gets interesting. A noticeable gap surrounds the inner disk and stretches for about 10 AU. Outside this unpopulated region lies an intermediate belt that runs from 83 to 104 AU. More emptiness encloses this structure until you reach the outer ring. This gap likely results from the gravitational effects of an unseen planet with a mass no greater than that of Saturn.

“The belts around Fomalhaut are kind of a mystery novel,” said University of Arizona astronomer and team member George Rieke in a press release. “Where are the planets? I think it’s not a very big leap to say there’s probably a really interesting planetary system around the star.” Team member Schuyler Wolff of the University of Arizona adds, “We definitely didn’t expect the more complex structure with the second intermediate belt and the broader asteroid belt.”

Indeed, our Sun doesn’t have anything like this two-tiered asteroid belt. And so far, these are the only two stars studied at this level of detail, leaving astronomers to wonder which architecture might be more common. The team plans to observe two other dust-wrapped stars, Vega and Epsilon (ϵ) Eridani, in the near future to find out.