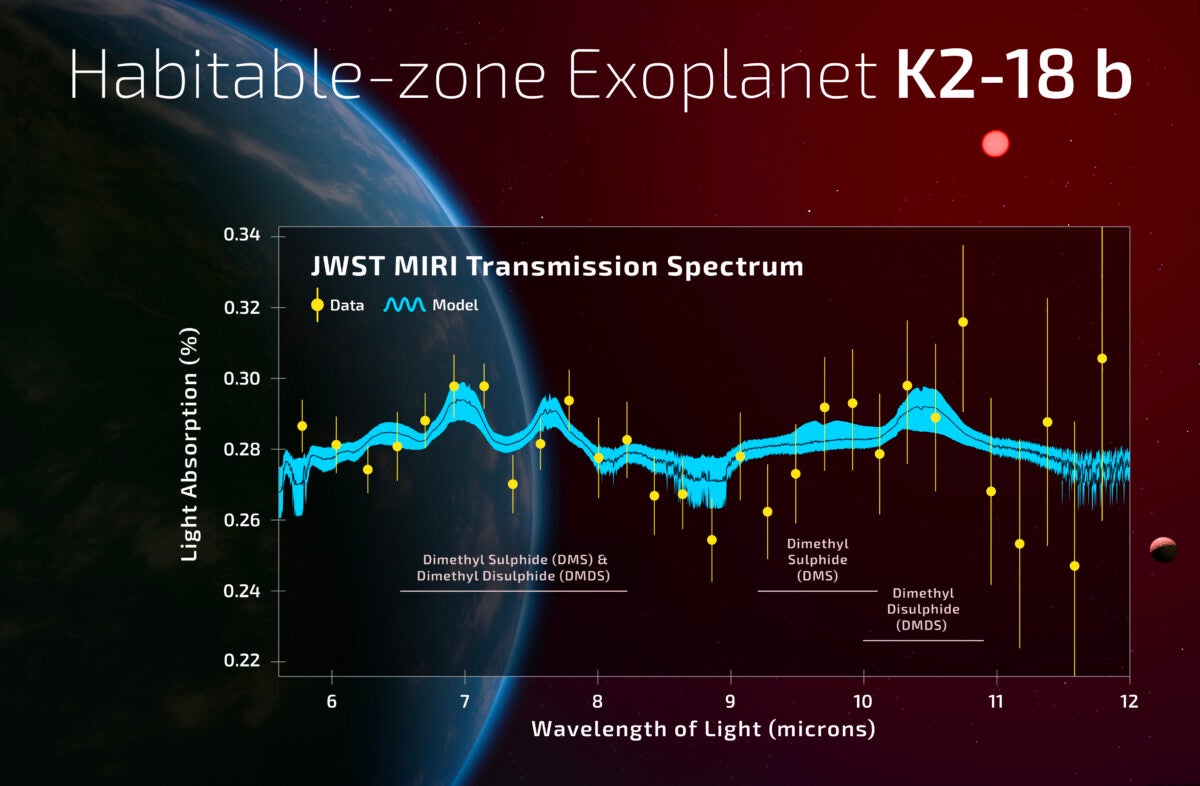

Scientists have reported new observations from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) that strengthen the case that the exoplanet K2-18 b has molecules in its atmosphere that, on Earth, are produced only by life.

The work, announced Wednesday, builds on previous observations from JWST published in 2023 by the same team that yielded weak hints of the molecule dimethyl sulfide (DMS) on K2-18 b, a planet that the team thinks could be covered with a global ocean. In the new data, additional spectra taken with a different onboard instrument have seen more evidence of the chemical signal of DMS, as well as signs of a related molecule, dimethyl disulfide (DMDS).

The team says they are not claiming to have discovered life, and that it is vital to collect more data to confirm the detection. However, they are not shying away from pointing out what they feel is the gravity of the moment — that detecting molecules that could be potential signs of life in other star systems are now within reach of our most powerful telescopes. In comments to media during an embargoed press conference on Tuesday reported by outlets like The New York Times, team leader Nikku Madhusudhan of the University of Cambridge, U.K. said that it was a “revolutionary moment.”

Madhusudhan also argued that the best explanation for the data is that K2-18 b hosts life. But in the astronomical community, that proposal has been met with a healthy dose of skepticism. Many praised the power of JWST to be able to attempt detections of such faint signals. But there was also widespread caution applied to any interpretations that invoke life, as recent studies have found that DMS can also be produced without life.

MIT planetary scientist Sara Seager told Astronomy that “with thousands of exoplanets in view, the temptation to overinterpret is strong — and some are jumping the gun. When it comes to K2-18 b, enthusiasm is outpacing evidence.”

Biosignature or not?

Lying 124 light-years away in the constellation Leo, K2-18 b orbits in the habitable zone of its red-dwarf host star — at a distance where the planet’s surface temperature can support liquid water. But at around 8 or 9 times as massive as Earth — equivalent to half the mass of the ice giant Neptune — it’s not clear what that surface is like.

The JWST observations that Madhusudhan’s team reported in 2023 showed clear signs of methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2) in its atmosphere. That, they argued, fits a scenario where a hydrogen-rich atmosphere surrounds a planet with a global water (H2O) ocean that could support life. They dubbed this scenario a “hycean” world, drawn from the words hydrogen and ocean. (Other studies, like one posted to the arXiv preprint server on the same day as the new work, say different scenarios are more likely for the planet. They include the possibility of a global magma ocean — “about as inhospitable as it gets,” says Seager — or a mostly gaseous makeup.)

At the time, the team also noted weak signs of DMS in the data, taken by JWST’s near-infrared spectrograph. DMS has been studied by astrobiologists for its potential to indicate life — what scientists call a biosignature — for over a decade. But the significance of the detection barely rose to a 2-sigma level, meaning there was a 5 percent probability of the signal appearing by chance — well short of the 5-sigma level considered to be the statistical gold standard in science.

RELATED: Did we find signs of life on K2-18 b? Not yet, but we might.

The new data come from JWST’s mid-infrared spectrograph and bring the detection up to a 3-sigma level, according to the team’s analysis, meaning there is a 0.3 percent probability of the data fitting the expected model spectrum for those molecules as well as it does purely by chance. With 16 to 24 additional hours of observing time, they think they can hit the 5-sigma mark — a 0.00006 percent probability of it fitting the model that well by chance. However, such statistical analyses can sometimes be misleading in that they do not take into account the possibility that the model is wrong, or that the data captured some other chemical that is mimicking the appearance of the model.

Even if the detection is confirmed, the question remains: How reliable is DMS as a biosignature? On Earth, DMS is produced by life like phytoplankton. It’s part of the smell of a sea breeze. And as far as scientists know, life is the only way DMS is produced on Earth.

But that doesn’t mean it can’t be produced by nonliving means elsewhere in the universe.

A year ago, researchers reported a detection of DMS on the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko — hardly a location brimming with life. (The team found the signal in archival data from the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission.) In September of last year, a team of researchers reported that in lab experiments, they were able to produce DMS by shining UV light on a simulated, hazy exoplanet atmosphere. This suggests that the reactions between a star’s photons and molecules in a planet’s atmosphere could provide a nonbiological way to produce DMS. And this February, a team of radio astronomers reported the detection of DMS in the gas and dust between stars. All of these results challenge the idea that DMS is a clear sign of life.

The team references the photochemical experiment in their paper, but argues that such reactions could not produce the amount of DMS they find on K2-18 b. Neither, they say, could comet impacts deliver DMS in the quantities that they observe with JWST.

In press

The new JWST results were publicized April 16 in a wave of news stories published at 7 p.m. EDT, accompanied by a press release from the University of Cambridge.

According to those reports, the paper was published April 16 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. When this story was first published, six hours later, the paper was not yet online at the link provided to journalists. However, during that time, a preprint of the manuscript was posted to the arXiv. (The paper eventually appeared on The Astrophysical Journal Letters website in the early morning EDT, listed with a publication date of April 17.)

In the Cambridge press release, Madhusudhan noted, “It’s important that we’re deeply skeptical of our own results, because it’s only by testing and testing again that we will be able to reach the point where we’re confident in them. … That’s how science has to work.”

NASA, which issued a press release when Madhusudhan and his colleagues’ previous JWST observations on K2-18 b were published, did not issue a press release on the new study.

But the agency did appear to distance itself from speculation about the “discovery of life” or “true biosignatures” in a statement to The Washington Post, suggesting that JWST data on its own might not be sufficiently convincing. Science reporter Joel Achenbach posted on Bluesky that NASA told him a “detection of a single potential biosignature would not constitute discovery of life. We would likely need multiple converging lines of evidence to confirm true biosignatures and rule out false positives, possibly including independent data from multiple missions.”

In other reactions, planetary scientist Sarah Hörst of Johns Hopkins University took to Bluesky to reject the claim that DMS amounts to a biosignature, pointing to the lab experiments that show it can be produced without life.

On the other hand, astrophysicist Adam Frank of the University of Rochester wrote, “This is sooooooooo exciting. Could go away with more data but it’s exactly the kind of path we’d expect on the road [to] finding life.”

David Kipping, an astronomer at Columbia University, posted on X that it was “Worth remembering that the detected molecule (DMS) does not necessarily mean life.” But, he added, it is ”exciting JWST can touch this sensitivity!”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated with additional quotes.