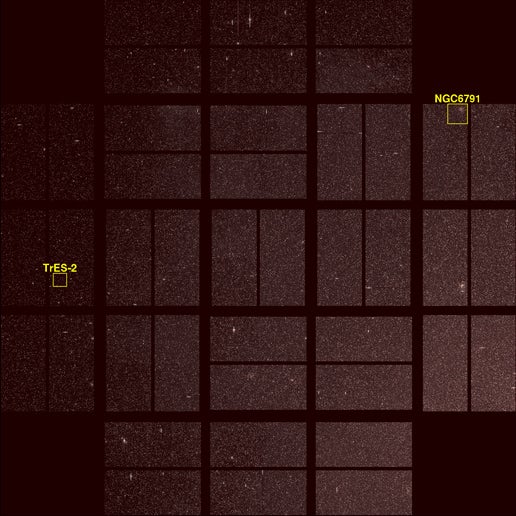

A cluster of stars, called NGC 6791, and a star with a known planet, called TrES-2, are outlined.

NASA’s Kepler mission has taken its first images of the star-rich sky where it will soon begin hunting for planets like Earth.

The new “first light” images show the mission’s target patch of sky, a vast starry field in the Cygnus-Lyra region of our Milky Way Galaxy. One image shows millions of stars in Kepler’s full field of view, while two others zoom in on portions of the larger region.

“Kepler’s first glimpse of the sky is awe-inspiring,” said Lia LaPiana, Kepler’s program executive at NASA headquarters in Washington. “To be able to see millions of stars in a single snapshot is simply breathtaking.”

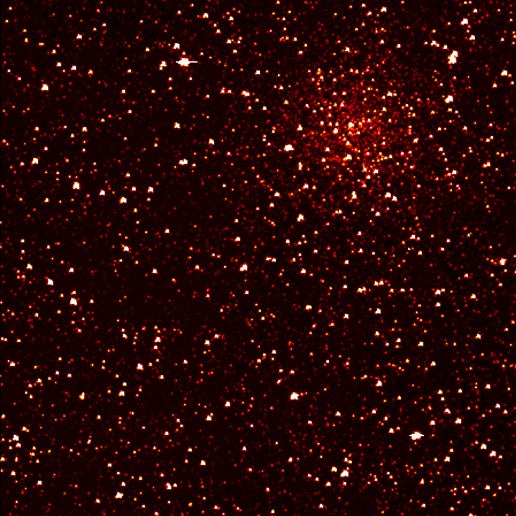

The area pictured is 0.2 percent of Kepler’s full field of view, and shows hundreds of stars in the constellation Lyra. The image has been color-coded so that brighter stars appear white, and fainter stars, red.

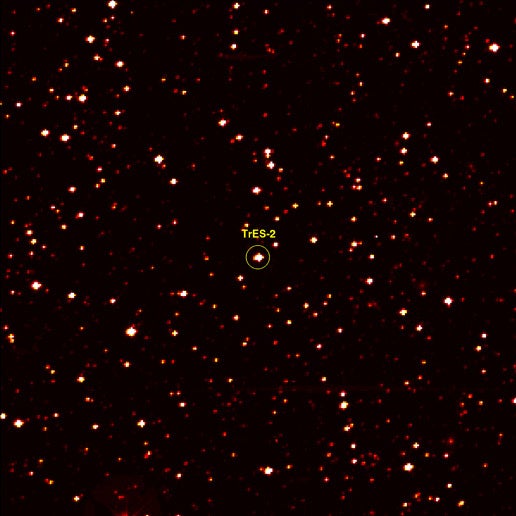

Two other views focus on just 1/1000 of the full field of view. In one image, a cluster of stars located about 13,000 light-years from Earth, called NGC 6791, can be seen in the lower left corner. The other image zooms in on a region containing a star, called Tres-2, with a known Jupiter-like planet orbiting every 2.5 days.

“It’s thrilling to see this treasure trove of stars,” said William Borucki, science principal investigator for Kepler at NASA’s Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, California. “We expect to find hundreds of planets circling those stars, and for the first time, we can look for Earth-size planets in the habitable zones around other stars like the Sun.”

The area pictured is 1/1000 of Kepler’s full field of view, and shows hundreds of stars at the very edge of the constellation Cygnus. The image has been color-coded so that brighter stars appear white, and fainter stars, red.

To find the planets, Kepler will stare at one large expanse of sky for the duration of its lifetime, looking for periodic dips in starlight that occur as planets circle in front of their stars and partially block the light. Its 95-megapixel camera, the largest ever launched into space, can detect tiny changes in a star’s brightness of only 20 parts per million. Images from the camera are intentionally blurred to minimize the number of bright stars that saturate the detectors. While some of the slightly saturated stars are candidates for planet searches, heavily saturated stars are not.

“Everything about Kepler has been optimized to find Earth-size planets,” said James Fanson, Kepler’s project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “Our images are road maps that will allow us, in a few years, to point to a star and say a world like ours is there.”

Scientists and engineers will spend the next few weeks calibrating Kepler’s science instrument, the photometer, and adjusting the telescope’s alignment to achieve the best focus. Once these steps are complete, the planet hunt will begin.