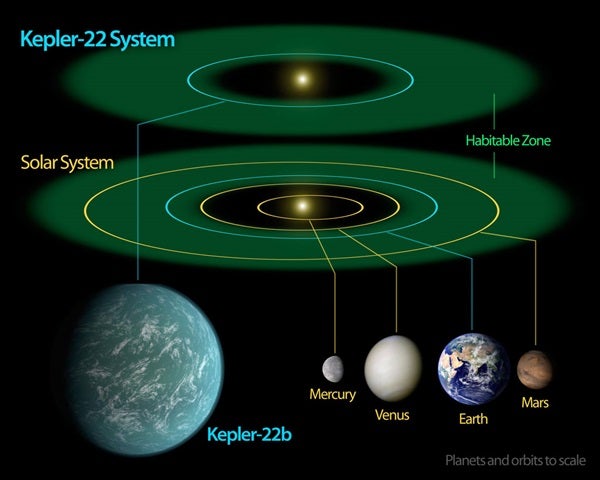

The newly confirmed planet, Kepler-22b, is the smallest yet found to orbit in the middle of the habitable zone of a star similar to our Sun. The planet is about 2.4 times the radius of Earth. Scientists don’t yet know if Kepler-22b has a predominantly rocky, gaseous, or liquid composition, but its discovery is a step closer to finding Earth-like planets.

Previous research hinted at the existence of near-Earth-sized planets in habitable zones, but clear confirmation proved elusive. Two other small planets orbiting stars smaller and cooler than our Sun recently were confirmed on the edges of the habitable zone, with orbits more closely resembling those of Venus and Mars.

“This is a major milestone on the road to finding Earth’s twin,” said Douglas Hudgins from NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “Kepler’s results continue to demonstrate the importance of NASA’s science missions, which aim to answer some of the biggest questions about our place in the universe.”

Kepler discovers planets and planet candidates by measuring dips in the brightness of more than 150,000 stars to search for planets that cross in front, or “transit,” the stars. Kepler requires at least three transits to verify a signal as a planet.

“Fortune smiled upon us with the detection of this planet,” said William Borucki from NASA Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, California. “The first transit was captured just three days after we declared the spacecraft operationally ready. We witnessed the defining third transit over the 2010 holiday season.”

The Kepler science team uses ground-based telescopes and the Spitzer Space Telescope to review observations on planet candidates the spacecraft finds. The star field that Kepler observes in the constellations Cygnus and Lyra are only visible from ground-based observatories in spring through early fall. The data from these other observations help determine which candidates can be validated as planets.

Kepler-22b is located 600 light-years away. While the planet is larger than Earth, its orbit of 290 days around a Sun-like star resembles that of our world. The planet’s host star belongs to the same class as our Sun, called G-type, although it is slightly smaller and cooler.

Of the 54 habitable zone planet candidates reported in February 2011, Kepler-22b is the first to be confirmed.

The Kepler team is hosting its inaugural science conference at Ames December 5–9, announcing 1,094 new planet candidate discoveries. Since the last catalog was released in February, the number of planet candidates identified by Kepler has increased by 89 percent, and now totals 2,326. Of these, 207 are approximately Earth-sized, 680 are super-Earth-sized, 1,181 are Neptune-sized, 203 are Jupiter-sized, and 55 are larger than Jupiter.

The findings, based on observations conducted May 2009 to September 2010, show a dramatic increase in the numbers of smaller-sized planet candidates.

Kepler observed many large planets in small orbits early in its mission, which were reflected in the February data release. Having had more time to observe three transits of planets with longer orbital periods, the new data suggest that planets one to four times the size of Earth may be abundant in the galaxy.

The number of Earth-sized and super-Earth-sized candidates has increased by more than 200 and 140 percent since February, respectively.

There are 48 planet candidates in their stars’ habitable zones. While this is a decrease from the 54 reported in February, the Kepler team has applied a stricter definition of what constitutes a habitable zone in the new catalog to account for the warming effect of atmospheres, which would move the zone away from the star out to longer orbital periods.

“The tremendous growth in the number of Earth-size candidates tells us that we’re honing in on the planets that Kepler was designed to detect: those that are not only Earth-size, but also are potentially habitable,” said Natalie Batalha from San Jose State University in California. “The more data we collect, the keener our eye for finding the smallest planets out at longer orbital periods.”

The newly confirmed planet, Kepler-22b, is the smallest yet found to orbit in the middle of the habitable zone of a star similar to our Sun. The planet is about 2.4 times the radius of Earth. Scientists don’t yet know if Kepler-22b has a predominantly rocky, gaseous, or liquid composition, but its discovery is a step closer to finding Earth-like planets.

Previous research hinted at the existence of near-Earth-sized planets in habitable zones, but clear confirmation proved elusive. Two other small planets orbiting stars smaller and cooler than our Sun recently were confirmed on the edges of the habitable zone, with orbits more closely resembling those of Venus and Mars.

“This is a major milestone on the road to finding Earth’s twin,” said Douglas Hudgins from NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “Kepler’s results continue to demonstrate the importance of NASA’s science missions, which aim to answer some of the biggest questions about our place in the universe.”

Kepler discovers planets and planet candidates by measuring dips in the brightness of more than 150,000 stars to search for planets that cross in front, or “transit,” the stars. Kepler requires at least three transits to verify a signal as a planet.

“Fortune smiled upon us with the detection of this planet,” said William Borucki from NASA Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, California. “The first transit was captured just three days after we declared the spacecraft operationally ready. We witnessed the defining third transit over the 2010 holiday season.”

The Kepler science team uses ground-based telescopes and the Spitzer Space Telescope to review observations on planet candidates the spacecraft finds. The star field that Kepler observes in the constellations Cygnus and Lyra are only visible from ground-based observatories in spring through early fall. The data from these other observations help determine which candidates can be validated as planets.

Kepler-22b is located 600 light-years away. While the planet is larger than Earth, its orbit of 290 days around a Sun-like star resembles that of our world. The planet’s host star belongs to the same class as our Sun, called G-type, although it is slightly smaller and cooler.

Of the 54 habitable zone planet candidates reported in February 2011, Kepler-22b is the first to be confirmed.

The Kepler team is hosting its inaugural science conference at Ames December 5–9, announcing 1,094 new planet candidate discoveries. Since the last catalog was released in February, the number of planet candidates identified by Kepler has increased by 89 percent, and now totals 2,326. Of these, 207 are approximately Earth-sized, 680 are super-Earth-sized, 1,181 are Neptune-sized, 203 are Jupiter-sized, and 55 are larger than Jupiter.

The findings, based on observations conducted May 2009 to September 2010, show a dramatic increase in the numbers of smaller-sized planet candidates.

Kepler observed many large planets in small orbits early in its mission, which were reflected in the February data release. Having had more time to observe three transits of planets with longer orbital periods, the new data suggest that planets one to four times the size of Earth may be abundant in the galaxy.

The number of Earth-sized and super-Earth-sized candidates has increased by more than 200 and 140 percent since February, respectively.

There are 48 planet candidates in their stars’ habitable zones. While this is a decrease from the 54 reported in February, the Kepler team has applied a stricter definition of what constitutes a habitable zone in the new catalog to account for the warming effect of atmospheres, which would move the zone away from the star out to longer orbital periods.

“The tremendous growth in the number of Earth-size candidates tells us that we’re honing in on the planets that Kepler was designed to detect: those that are not only Earth-size, but also are potentially habitable,” said Natalie Batalha from San Jose State University in California. “The more data we collect, the keener our eye for finding the smallest planets out at longer orbital periods.”