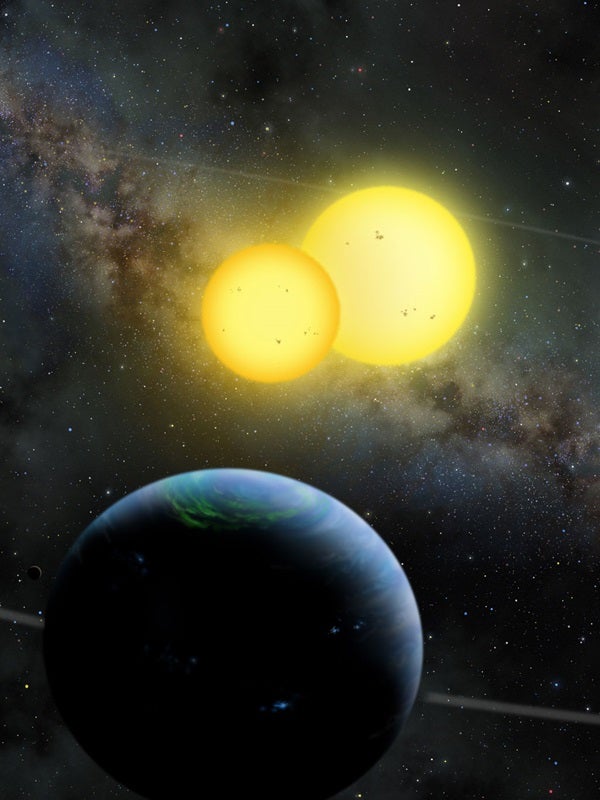

The two new planets, named Kepler-34b and Kepler-35b, are both gaseous Saturn-sized planets. Kepler-34b orbits its two Sun-like stars every 289 days, and the stars themselves orbit and eclipse each other every 28 days. The eclipses allow a precise determination of the stars’ sizes. Kepler-35b revolves about a pair of smaller stars (80 and 89 percent of the Sun’s mass) every 131 days, and the stars orbit and eclipse one another every 21 days. Both systems reside in the constellation Cygnus, with Kepler-34 at 4,900 light-years from Earth and Kepler-35 at 5,400 light-years, making these among the most distant planets discovered.

While long anticipated in both science and science fiction, the existence of a circumbinary planet orbiting a pair of normal stars was not definitively established until the discovery of Kepler-16b. Like Kepler-16b, these new planets also transit (eclipse) their host stars, making their existence unambiguous. When only Kepler-16b was known, many questions remained about the nature of circumbinary planets — what kinds of orbits, masses, radii, temperatures, etc., could they have? And most of all, was Kepler-16b just a fluke? With the discovery of Kepler-34b and 35b, astronomers can now answer many of those questions and begin to study an entirely new class of planets.

“It was once believed that the environment around a pair of stars would be too chaotic for a circumbinary planet to form, but now that we have confirmed three such planets, we know that it is possible, if not probable, that there are at least millions in the galaxy,” said William Welsh from San Diego State University, California, who led the team of 46 investigators involved in this research.

“With this paper, the new field of comparative circumbinary planetology is now established,” said Laurance Doyle from the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California.

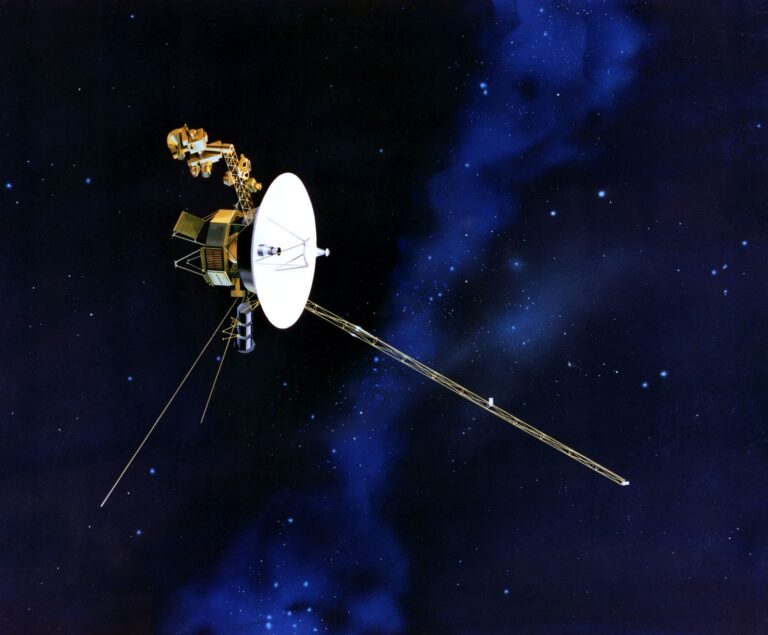

The discovery was made possible by the three unique capabilities of the Kepler space telescope: its ultra-high precision, its ability to simultaneously observe roughly 160,000 stars, and its long-duration, near-continuous measurements of the brightness of stars. Additional work using ground-based telescopes provided velocity measurements of the stars needed to confirm that these candidates are really planets. “The search is on for more circumbinary planets,” said Joshua Carter from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, “and we hope to use Kepler for years to come.”

A circumbinary planet has two suns, not just one. The distances between the planet and stars are continually changing due to their orbital motion, so the amount of sunlight the planet receives varies dramatically. “These planets can have really crazy climates that no other type of planet could have,” said Jerome Orosz from San Diego State University. “It would be like cycling through all four seasons many times per year, with huge temperature changes.”

Welsh added, “The effects of these climate swings on the atmospheric dynamics, and ultimately on the evolution of life on habitable circumbinary planets, is a fascinating topic that we are just beginning to explore.”