Four hundred years ago, skywatchers across Europe and Asia witnessed the birth of a “new star,” or nova. First spied the evening of October 9, the object gleamed brightly low in the southwestern sky, rivaling the nearby planet Mars. Within days, it had surpassed the equally close Jupiter, making it the brightest object in the night sky.

A spell of cloudy weather over Prague kept the most famous astronomer of the day, Johannes Kepler, from viewing the new star until October 17. But once he started, Kepler never relented. He studied the object every clear night for more than a year, until it faded below naked-eye visibility in March 1606. (Alas, the invention of the telescope still lay 3 years in the future, so it couldn’t be followed any longer.)

Astronomers ultimately rewarded Kepler’s perseverance by naming the new star after him. Now known to have been a supernova — a titanic explosion signaling the death of a star rather than the birth of a new one — Kepler’s supernova stands as one of only six such explosions observed in our galaxy in the past 1,000 years. Of course, Kepler and his contemporaries had no clue what it was they were seeing.

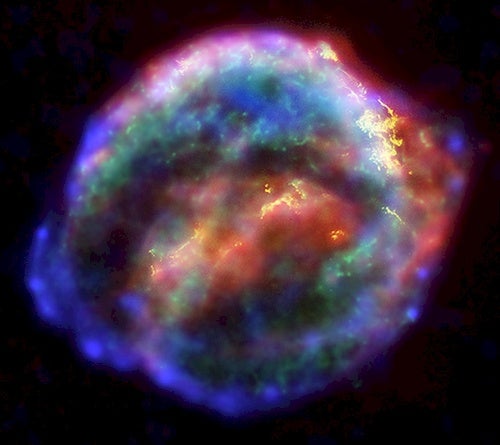

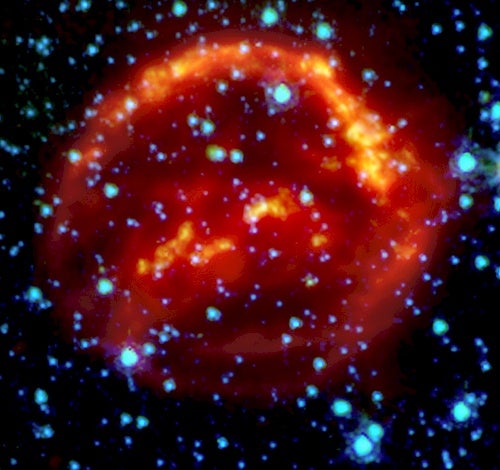

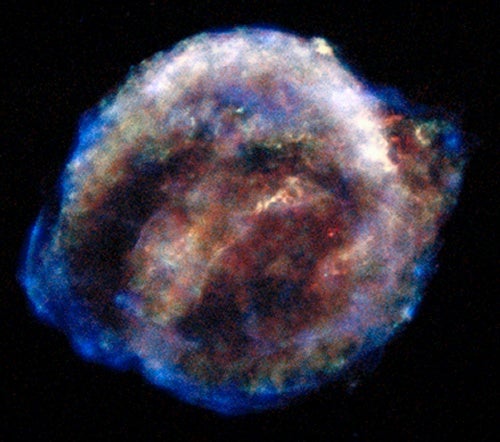

“Multi-wavelength studies are absolutely essential for putting together a complete picture of how supernova remnants evolve,” says Ravi Sankrit of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, who led the team using Hubble. “The glow from young remnants, such as Kepler’s supernova remnant, comes from several components. Each component shows up best at different wavelengths.”

The combined image of Kepler’s supernova remnant shows a fast-moving shell of iron-rich material from the exploded star surrounded by an expanding shock wave that is sweeping up interstellar gas and dust. (When the star exploded, the blast ripped the star apart and unleashed a roughly spherical shock wave expanding at more than 20 million mph.) “The infrared data are dominated by heated interstellar dust, while optical and X-ray observations sample different temperatures of gas,” says Johns Hopkins astronomer William Blair, who led the Spitzer team.

The Hubble observations show where the supernova’s shock wave is ramming into high-density regions in the surrounding gas. Dense clumps of material formed from instabilities created just behind the advancing shock wave glow brightly in visible light. Comparing the Hubble image with earlier ground-based images yielded the first good distance measurement for this supernova: 13,000 light-years.

The Chandra observations show regions of much hotter gas. The hottest regions, which emit the highest-energy X rays, come from the area immediately behind the shock front. These regions line up with the regions seen by Hubble. Cooler X-ray-emitting gas fills the interior shell and marks heated ejecta expelled by the exploded star. Finally, the Spitzer data reveal microscopic dust particles heated by the shock wave that then re-radiate the energy at infrared wavelengths. The remnant glows brightest in the infrared just outside the bright regions seen by Hubble.

Follow-up observations eventually may reveal what type of star Kepler saw exploding. Nature has devised two ways to detonate a star. In one, a massive star reaching the end of its life runs out of fuel for nuclear reactions. This triggers a core collapse and subsequent explosion, leaving behind a neutron star or black hole. In the second, a white dwarf star in a binary system accumulates too much material from its bloated companion. Eventually, the star can no longer support itself and gets completely incinerated. Kepler’s supernova remains the only blast seen in the Milky Way whose nature has not been pinned down. With a little luck from Hubble and its friends, that may soon change.