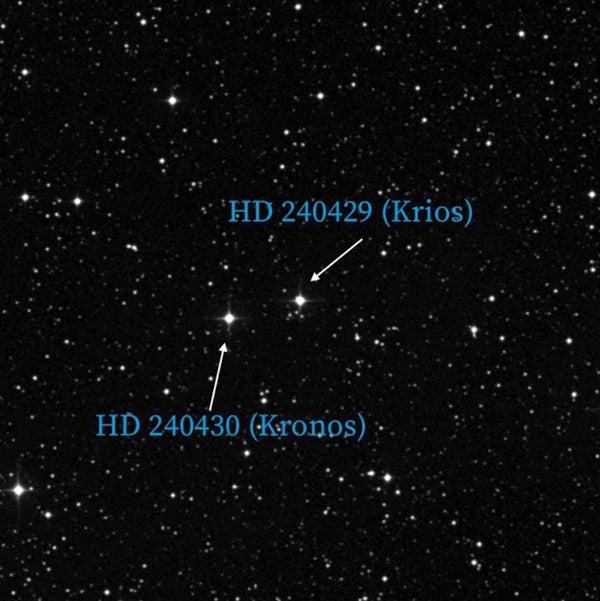

On September 15, a team of Princeton astronomers posted a paper on the physics pre-print site arXiv.org that argues the star Kronos devoured over a dozen of its rocky inner planets during the course of its 4 billion year lifetime. However, its companion star, Krios (HD 240429), has managed to avoid feasting on its own solid worlds.

The lead author of the study, Semyeong Oh, explained in a press release that Kronos — named after the mythological Greek Titan who ate his own children — is the most obvious and dramatic example yet of a Sun-like star consuming its own planets. And, “because [Kronos] has a stellar companion to compare it to, it makes the case a little stronger,” she said.

Initially, Oh and her team were not trying to find a planet-eating star and its thin twin. Instead, they were using new stellar data collected by the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft to simply identify co-moving stars that formed together from the same materials around the same time.

While Kronos and Krios have about the same amount of volatile elements — those that are typically found in gas form — Kronos has a strikingly high amount of rock-forming minerals, such as iron, aluminum, silicon, and magnesium. According to Oh, most stars that are as metal-rich as Kronos “have all the other elements enhanced at a similar level, whereas Kronos has volatile elements suppressed, which makes it really weird in the general context of stellar abundance patterns.”

After carefully verifying the data was accurate, the team set out to determine what had caused this discrepancy in composition between Kronos and Krios. Could the stars have formed their planetary disks at different times? Unlikely based on their age. Maybe the two stars were not always co-moving and swapped partners at some point? Oh performed a straightforward calculation to disprove this theory.

The answer finally struck Oh when she started plotting chemical abundance as a function of condensation temperature — the temperature at which volatiles form into solids. She quickly noticed that Kronos was lacking every element that solidifies below 1,700 Fahrenheit, while it was rich in elements that form solids at higher temperatures.

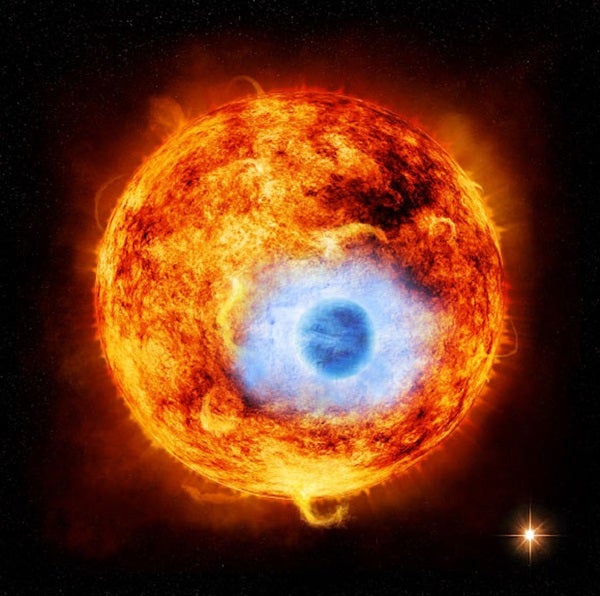

“All of the elements that would make up a rocky planet are exactly the elements that are enhanced on Kronos, and the volatile elements are not enhanced,” Oh said, “so that provides a strong argument for a planet engulfment scenario, instead of something else.” In order for Kronos to be this metal-rich while lacking many volatiles, Oh and her team calculated the star would need to gobble up roughly 15 Earth-mass planets.

Though the exact process that led to Kronos devouring its inner planets is not known, Oh and her colleagues have some theories. The leading one is that Kronos and Krios once flew too close to another star, which stretched out the orbits of Kronos’s outermost planets. This caused the outer planets to careen through the inner solar system, in turn catapulting the rocky inner planets into death-spiral orbits with Kronos. Their theory, however, would require that Krios managed to somehow avoid a similar doomsday scenario. But considering the twin stars are so far apart that they only orbit each other about once every 10,000 years, it is entirely possible.

Equipped with their results, Oh and Price-Whelan both believe future study of the Kronos-Krios system is needed to help understand how different solar systems can form and evolve over time. “One of the common assumptions (well-motivated, but it is an assumption) that’s pervasive through galactic astronomy right now is that stars are born with [chemical] abundances, and they then keep those abundances,” Prince-Whelan said. “[Kronos] is an indication that, at least in some cases, that is catastrophically false.”