Titan, second in size only to Jupiter’s Ganymede, is the only moon with an atmosphere. Composed of nitrogen, methane, ethane, and propane, Titan’s thick, hazy, and all but impenetrable atmosphere hides the largest single expanse of unexplored terrain remaining in our solar system. Changing this is a core element of Cassini’s mission — the orbiter will perform three flybys of the moon, and the Huygens probe it carries will examine it directly in 2005.

In the meantime, Cassini’s cameras have started taking pictures. The spacecraft’s narrow-angle camera has a spectral filter specifically designed to penetrate Titan’s hazy atmosphere. Images taken in mid-April show surface features previously visible only from the most powerful Earth-based telescopes.

Even though Cassini is not currently positioned for optimal Titan-viewing, the camera still was able to resolve features several hundred miles across. Over the next two months, as the Titan-viewing improves, features as small as 28 miles (44 kilometers) across should be apparent.

Cassini’s next chance to image the moon will be on July 2, when it comes within 217,500 miles (350,000 km) of Titan’s south pole. If the spacecraft’s cameras can see Titan’s surface, it’s possible that some of the moon’s geological features will be familiar to earthbound observers: mountains, canyons, craters, rivers, lakes, shorelines, and snowfields are all possibilities. But because of the frigid temperatures on the satellite — around -300° F (-184° C) — and the very un-earthlike materials in its atmosphere, scientists are expecting the unexpected.

Recent spectroscopic and radar observations suggest that Titan boasts huge lakes of liquid hydrocarbons on its surface, as well as a methane-based meteorological cycle similar to Earth’s hydrological cycle. This means Titan is the only other known object with rain and surface oceans, and scientists believe it may be a good model for studying pre-biotic chemistry and the origin of life on Earth.

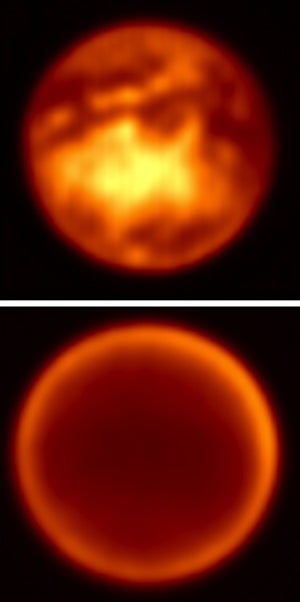

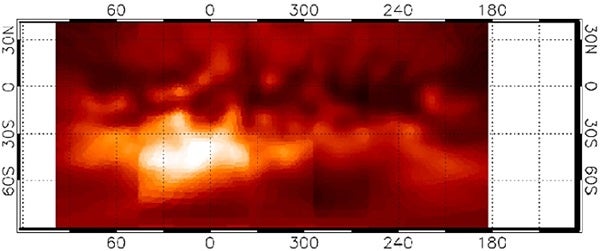

While Cassini has turned its eye toward Titan, Earth-based telescopes are doing likewise. Images obtained in February by the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) had unprecedented spatial resolution and the lowest contamination of atmospheric condensates yet, enabling the team to map approximately three-quarters of Titan’s surface.

The VLT images were made with a recently installed device called the Simultaneous Differential Imager (SDI). With the high-contrast SDI camera, it’s possible to obtain very sharp images in three colors simultaneously. While the device mainly is used for imaging extrasolar planets, it’s also turned out to be very useful for other objects with thick atmospheres, like Titan.

The Cassini imaging team hopes to be able to make its own map of Titan’s features in another month or so.