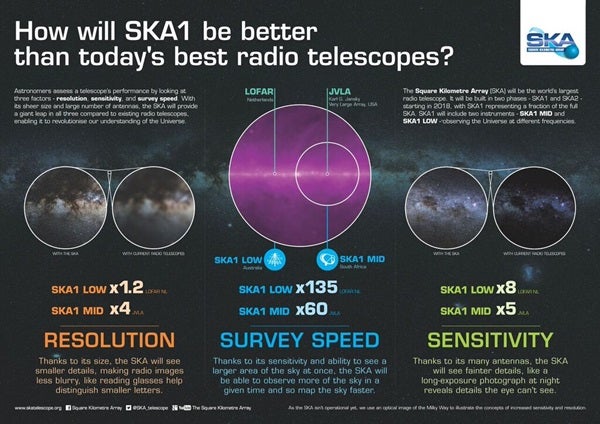

Pulsar emissions and gravitational waves have been telling us interesting things about the universe, and upcoming research is likely to bring improved and exciting insights. The SKA will be far more powerful and versatile than any telescopes before it, allowing for a diverse range of in-depth research.

“What excites me is the finding of the unexpected,” SKA Science Director Robert Braun said. “You’ll be looking for one phenomenon, and you come away finding something completely unpredicted.”

Pulsars are excellent timekeepers. As pulsars rotate on their axis, for a few milliseconds the radio waves they emit are shot directly at Earth, where researchers can record and analyze them. They rotate very consistently, so researchers can use them as precise clocks for experiments.

The consistency of pulsars also makes them a reliable way to study gravitational waves. Gravitational waves warp space-time so that anything in their path is warped itself. If a gravitational wave from a pair of supermassive black holes orbiting each other were to propagate through the space between a pulsar and our planet, researchers would be able to detect a slight delay in the radio signal received, as space would be physically distorted. The SKA telescope will be able to use pulsars to detect gravitational waves from distant supermassive black holes binaries in more precise ways that current telescopes.

According to Alberto Sesana, a research fellow at the University of Birmingham, a great challenge to searching for evidence of gravitational waves in pulsar radio emissions is separating the signals from the plethora of other sources of noise in the universe.

“When it comes to gravitational wave detection, the hardest part is that we do not understand the intrinsic noise of pulsars very well.” Sesana said. “This is a problem, because detecting a signal means to single it out from noise and if you don’t know what your noise does, it becomes difficult to identify the signal.”

It’s a bit like being at a concert with your eyes closed and trying to decipher which speaker is playing the bass guitar.

Tests of General Relativity

Until the first gravitational wave signal detected by LIGO, pairings of neutron stars were the best test of general relativity. According to the theory, the emission of gravitational waves as the stars rotate around each other causes the distance between the two neutron stars to shrink. This in turn shrinks the amount of time it takes the stars to orbit each other, and affects the timing of the pulsars. Studying these timing changes closely will allow researchers to pinpoint the rate of shrinkage in a concrete manner and compare it to what the theory of general relativity says will happen.

In future studies, SKA telescopes plan to find more binary systems like this, which will help build a stronger body of evidence for or against our current theory of general relativity.

“With better telescopes and algorithms, we can find more pulsars, and among them, more exotic objects, like double neutron star binaries, which will help constrain general relativity, and pulsar – white dwarf binaries, which will help constrain alternative theories of gravity,” said Delphine Perrodin, a researcher at the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF).

Alternative Theories of Gravity

Pulsar-white dwarf systems can similarly test alternative theories of gravity. PSR J0337+1715 is a great example of this type of system. For the visual learners, here’s a short video describing this system:

This is an important area of study because general relativity is not yet a completely sound theory. The theories of general relativity and quantum mechanics have been studied extensively, but physicists still cannot reconcile them with each other.

The PSR J0337+1715 system has interested physicists since its discovery in 2007. Two white dwarfs orbit the pulsar – one very closely and one from far away. This system is fascinating because the outer white dwarf’s gravitational field accelerates the orbits of the inner pair at a much faster rate than predicted by current theories. With more sensitive telescopes, researchers aim to find more systems like this to study to more fully understand, among other things, the Strong Equivalence Principle (SEP). SEP states that the laws of gravity are not affected by velocity and location, but the way the PSR J0337+1715 system behaves, it appears that there is something beyond our understanding to be discovered. The SKA telescope will be able to more precisely study this supposed violation.

Whatever conclusions come from it, physicists will either pin down more accurate descriptions of the SEP and alternative theories of gravity, or may find they need to scrap these theories entirely.

SKA will practically revolutionize the study of astrophysics, and will even contribute to other fields of physics. With such a wide range of capability, SKA will advance theories of dark matter and dark energy, learn about galaxy formation in the early and local universe, and hopefully accurately locate the first recognized pair of supermassive black holes. Researchers hope to use the SKA to formulate a “movie” of the early universe’s progression to its current state by studying hydrogen recombination after the Big Bang.

“If we can overcome the instrumental challenges, we’ll be able to see that ‘cosmic dawn,’ the first moments of time in which the universe starts to become ionized and watch as that ionization progresses,” Braun said.

According to Sesana, the holy grail of this research would be to find interesting objects that are closer and easier to study.

“Another ideal outcome will be to find, possibly – and this would be a dream – a pulsar closely orbiting the supermassive black hole in the Milky Way center. This will allow the testing of general relativity like in the pulsar-black hole case, but to an even greater precision.”

Exciting Discoveries Ahead

The potential to discover groundbreaking phenomena in the universe is awe-inspiring to say the least. Some questions will be answered, but many more questions will be raised.

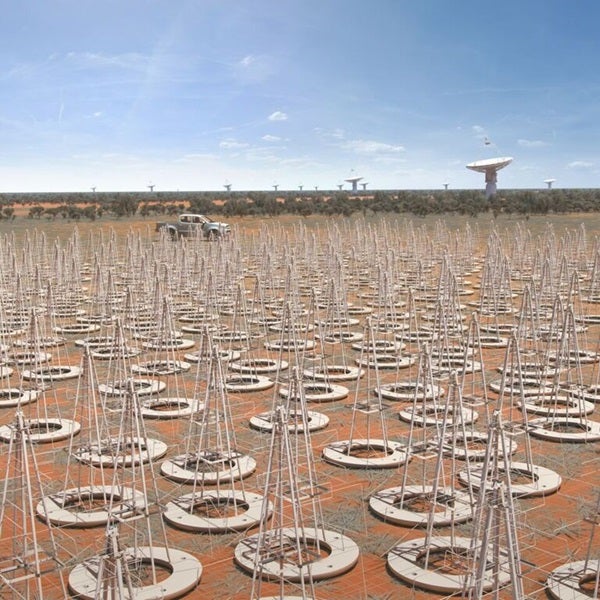

The overarching SKA project hopes to see an intergovernmental treaty signed in 2018, and should begin its five-year construction in 2019 or 2020. Braun says that the South African MeerKAT radio telescope, which is a precursor project that will be integrated into the SKA, is nearing completion and expects to be functioning in April 2018. Other first-class science precursor facilities located such as ASKAP and the MWA radio telescopes in Australia are already paving the way for SKA, as well as a number of smaller facilities around the world

The wait seems long, but for astronomy fans, it’s going to be well worth it.