In the 125 years since Percival’s arrival in Flagstaff, his observatory has evolved considerably. Known to many as America’s Observatory, the site now boasts a research faculty of 14 Ph.D.-level astronomers and an informal outreach program that draws more than 100,000 visitors to the campus each year.

Telescopes then and now

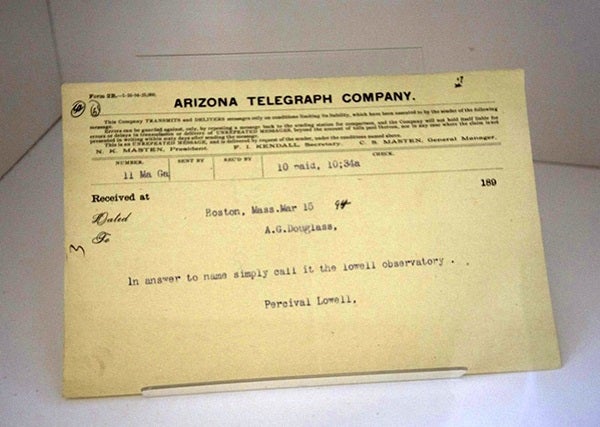

Lowell Observatory has long benefited from ownership of some of the finest tools of the astronomer’s trade. And while a comprehensive description of all of them could fill a book, two are especially distinguished: The famed Clark Telescope and the Discovery Channel Telescope.

Shortly after founding the observatory, Lowell commissioned a 24-inch refractor from Alvan Clark & Sons in Boston for the princely sum of $20,000, which equates to about $600,000 today. The telescope still graces its historic dome overlooking Flagstaff. It is now used solely to give the public spectacular views of the universe, but it has played a role in some of the most important observations of the 20th century.

The modern bookend to the historic Clark telescope is Lowell’s 4.3-meter Discovery Channel Telescope (DCT), taking its name from the well-known media company. Discovery founder and former CEO John Hendricks has long been a member of the observatory’s Advisory Board. And Discovery, Hendricks, and his wife, Maureen, made gifts totaling $16 million toward the $53 million cost of the project. These were gifts, not purchases: Discovery has no ownership of the telescope, nor any direction regarding the research it conducts. In return for their contributions, they received naming rights and first right of refusal for use of images in educational broadcasts. The research carried out with DCT proceeds as it would at any other professional telescope.

Groundbreaking for the DCT occurred on an especially hot day in July 2005. The first-light gala celebration was almost exactly seven years later, featuring a marvelous keynote address by Neil Armstrong — his final public appearance before his death several weeks later. Today, the fully commissioned telescope operates night in and night out at an elevation of about 7,800 feet (2,400 meters), some 40 miles (64 km) southeast of Flagstaff in Happy Jack, Arizona. Its finely figured thin meniscus primary mirror, held in shape by a 156-element active optics system, regularly delivers impeccable seeing — a measure of the sharpness of a telescope’s image — to any of its five instruments at the Ritchey-Chrétien focus. The DCT can switch between any of these instruments in about a minute, making it uniquely suited for observing programs that target quickly evolving cosmic objects, such as gamma-ray bursts and supernovae. Boston University, the University of Maryland, the University of Toledo, Northern Arizona University, and Yale University have joined Lowell as partners with access to the DCT, and the consensus of its users is that the DCT is one of the best-performing and most efficient 4-meter telescopes they have experienced. It is a testament to the outstanding engineers who built and maintain it, and it will be Lowell’s research flagship for decades to come.

A scientific haven

The core of Lowell’s research philosophy is to provide outstanding telescopes and instrumentation and then let its faculty use them to do whatever science they find interesting. Astronomers coming to Mars Hill are handed, in effect, an academic blank check. Lowell welcomes projects that take longer to complete than the three-year cadence of a typical research grant. Also welcomed are ideas that might be given the slightly derisive term “fishing expeditions.” Sometimes such pursuits are indeed dead ends — though dead ends can also be decidedly revealing — but sometimes you catch some very interesting fish. Perhaps the most dramatic example is Slipher’s spectroscopic observations of “spiral nebulae,” which Lowell pushed for to see if their compositions matched those of the solar system’s gas giants. Unlike Slipher’s measurements of Andromeda, many of these objects showed recessional velocities, which proved to be the first evidence of the expanding universe.

The great demotion

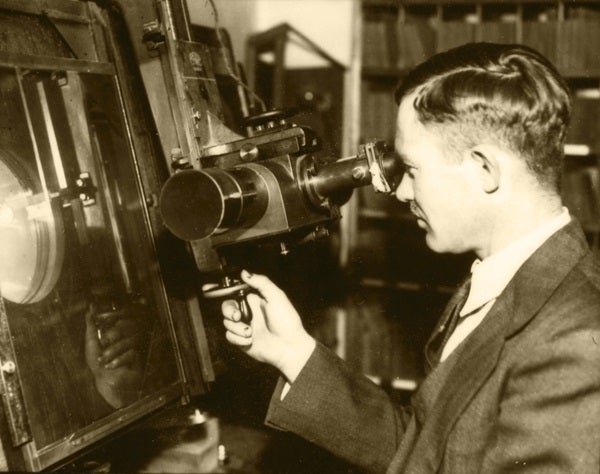

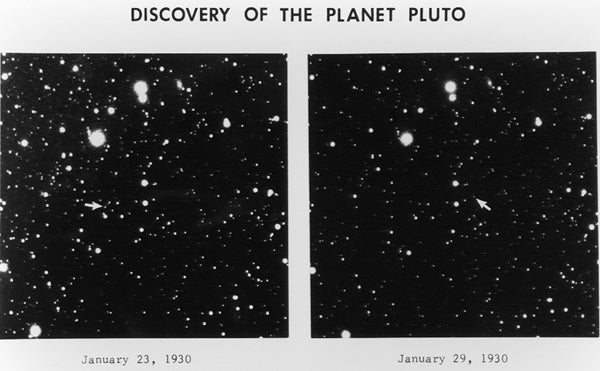

Slipher’s redshift observations are arguably the most fundamental astronomical observations ever made at Lowell, but surely one of the best known is the discovery of Pluto. Spurred on by perturbations found in Uranus’ orbit in the late 19th century, Lowell spent the latter years of his life searching for a possible ninth planet whose gravitational pull could explain Uranus’ orbital oddities. He dubbed the predicted world Planet X.

Ninety years ago, on February 18, 1930, Clyde Tombaugh walked into Slipher’s office and said, with what must have been trembling excitement, “I have found your Planet X.” Eventually, the distant and diminutive world showed it was not gravitationally assertive enough to be the Planet X Percival Lowell had in mind. Instead, it was an enigmatic little object revealed in detail only in July 2015 during the historic New Horizons flyby — a mission in which current and former Lowell astronomers have played a pivotal role.

Consider the Pluto of today, as further revealed by New Horizons, for which Lowell scientist Will Grundy leads the surface composition team. Pluto, we now know, is a place with five moons, a complex atmosphere, variegated terrain and surface regions, and patently active geology. Holding all this up to the idiosyncrasies of the other planets and non-planets in the solar system, as well as to the strange and new planetary characteristics and system architectures being revealed around most planet-harboring stars, one could argue it might be a reasonable time to reexamine this matter. Perhaps we would arrive at a more thoughtful taxonomy than we currently have.

Bringing science to everyone

Percival Lowell was much more than just an impressive businessman and academic. He was also an avowed popularizer of astronomy. His controversial ideas about Mars were often aired to the irritation of the professional community. But he also inspired many with his belief that the excitement of scientific discovery should be shared with everyone, making them “co-discoverers” of the objects, laws, and phenomena that make up our weird and wonderful universe.

Lowell Observatory continues that commitment today as an integral part of its mission. The observatory’s modest, one-room operation of the early 1990s expanded dramatically in 1994 with the opening of the Steele Visitor Center. Visitation at Lowell then held steady at 60,000 to 70,000 people per year until the New Horizons flyby, when it rose sharply and has since remained at 100,000 or more.

In response to this example of a good problem to have, Lowell is now in the advanced stages of design and fundraising for a new $29 million, 32,000-square-foot (3,000 square meters) visitor facility.

As a nonprofit institution, Lowell relies increasingly on philanthropy to support research as well as outreach. And in June 2019, the observatory staff was thrilled to announce the naming of the Kemper and Ethel Marley Foundation Astronomy Discovery Center, the result of a $14.5 million pledge from the eponymous foundation to fund 50 percent of the center’s cost. Lowell is now proceeding full steam ahead with the remaining fundraising, and our goal is to open the new center in 2023. Our vision is for it to be the premier facility in the world for communicating the marvels of the universe to all.

In the meantime, to alleviate crowding and long lines, in the fall of 2019, Lowell opened the $4 million Giovale Open Deck Observatory, a suite of six permanently mounted telescopes under a roll-off building. Among the instruments are a 0.8-meter Starstructure Dobsonian, 0.6-meter and 0.5-meter PlaneWave reflectors, and a strikingly beautiful 0.2-meter Moonraker refractor. Exhibits, a classroom, a huge planisphere, and our own version of Stonehenge will further enhance the experience. The technical description of this new public observing plaza — at least, according to many of our visitors — is “way cool.”

Why?

For all of us who love our calling, it’s fun to talk about what we do. But it’s perhaps trickier, albeit equally or more important, to understand and discuss why we do it.

Lowell’s employees often speak of their mission as encompassing dual pillars of research and outreach, but they are, in fact, both related components of the unified goal of communicating science. Whether our audience is a professional astronomer reading an Astrophysical Journal article by a Lowell researcher or a 12-year-old asking one of Lowell’s educators about the workings of a black hole, the observatory communicates the wonders of the universe and promotes scientific, evidence-based curiosity and thinking.

Any way you choose to interact with Lowell Observatory, the goal is to have you come away with the simple pleasure of knowing something you didn’t before, such as a perspective or idea about our universe that provides you with a new insight into how this vast physical system works.

Those at Lowell want you to feel curious. You don’t need to visit the observatory or read a research paper to find out the mass of Jupiter or to get a list of the names of all the planets; you can get this information off the internet. More important is wondering about the greater whole that might come into focus after learning about the smaller parts. What can humans deduce from the store of knowledge with which we’ve armed ourselves?

Lowell Observatory wants everyone to feel comfortable with the unfamiliar. What we know about the universe pales in comparison to what we don’t. We live in a cosmic sea of uncertainty, a universe governed by the strikingly counterintuitive rules of relativity and quantum mechanics. It’s a place where our perceptions are often well out of sync with reality. However, all too often, our public discourse and policy decisions are ruled by absolute certainty in the correctness of our point of view and the feeling that those who hold different points of view are idiots — or, worse, enemies.

Science, in contrast, is about deeply exploring data, taking pleasure in the power of codifying and understanding physical principles in the beautiful language of mathematics, and maintaining open-mindedness to challenges to long-held beliefs. Imagine the beauty of a world in which all of us do not reject the unfamiliar, but instead embrace it.

And Lowell Observatory wants everyone to feel humble. A good scientist should always hold the sentence, “I might be wrong,” front and center in their mind. Experiencing the universe in all its vast weirdness encourages us to wonder, to feel humble, and to be willing to change our minds when the data demand that we do.

Some years back, an email arrived from a mom in a state far from Arizona. She and her family had visited Lowell, and afterward, their son was so excited by what he had experienced that he promptly went home and wrote a school report about Clyde Tombaugh and his discovery of Pluto. She wrote in her email that Lowell educators had “amazed, challenged, and opened a young mind.”

That is why we do what we do. For young and old, amateur astronomers and professionals, everyone who wonders about the incredible sights that wheel overhead every night, we want to amaze and challenge, and to show how much fun it is to be part of the uncertainty and excitement of discovery.

And this is not merely doing well by doing good. In today’s rapidly evolving, technical, and often fraught world, it is a societal and national imperative. We welcome all to join us on the journey.