Newly discovered cliffs in the lunar crust indicate the Moon shrank globally in the geologically recent past and might still be shrinking today, according to a team analyzing new images from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) spacecraft. The results provide important clues to the Moon’s recent geologic and tectonic evolution.

The Moon formed in a chaotic environment of intense bombardment by asteroids and meteors. These collisions, along with the decay of radioactive elements, made the Moon hot. The Moon cooled off as it aged, and scientists have long thought the Moon shrank over time as it cooled, especially in its early history. The new research reveals relatively recent tectonic activity connected to the long-lived cooling and associated contraction of the lunar interior.

“We estimate these cliffs, called lobate scarps, formed less than a billion years ago, and they could be as young as a hundred million years,” said Thomas Watters from the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, Washington, D.C. While ancient in human terms, it is less than 25 percent of the Moon’s current age of more than 4 billion years. “Based on the size of the scarps, we estimate the distance between the Moon’s center and its surface shrank by about 300 feet,” said Watters.

“These exciting results highlight the importance of global observations for understanding global processes,” said John Keller from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “As the LRO mission continues to a new phase with emphasis on science measurements, our ability to create inventories of lunar geologic features will be a powerful tool for understanding the history of the Moon and the solar system.”

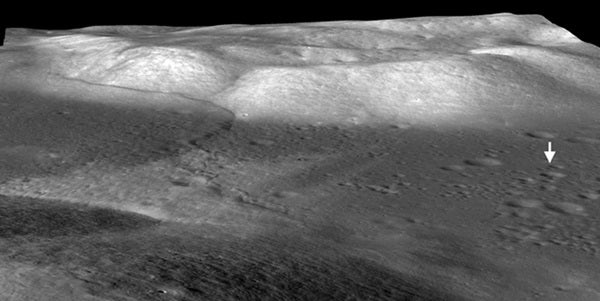

The scarps are relatively small; the largest is about 300 feet (90 meters) high and extends for several miles or so, but typical lengths are shorter and heights are more in the tens of yards (meters) range. The team believes they are among the freshest features on the Moon, in part, because they cut across small craters. Because the Moon is constantly bombarded by meteors, features like small craters — those less than about 1,200 feet (370 meters) across — are likely to be young because they are quickly destroyed by other impacts and don’t last long. So, if a scarp has disrupted a small crater, the scarp formed after the crater and is even younger. Even more compelling evidence is that large craters, which are likely to be old, don’t appear on top any of the scarps, and the scarps look crisp and relatively undegraded.

Lobate scarps on the Moon were discovered during the Apollo missions with analysis of pictures from the high-resolution Panoramic Camera installed on Apollo 15, 16, and 17. However, these missions orbited over regions near the lunar equator, and were only able to photograph 20 percent of the lunar surface, so researchers couldn’t be sure the scarps were not just the result of local activity around the equator. The team found 14 previously undetected scarps in the LRO images, seven of which are at high latitudes (more than 60°). This confirms that the scarps are a global phenomenon, making a shrinking Moon the most likely explanation for their wide distribution, according to the team.

As the Moon contracted, the mantle and surface crust were forced to respond, forming thrust faults where a section of the crust cracks and juts out over another. Many of the resulting cliffs, or scarps, have a semicircular or lobe-shaped appearance, giving rise to the term “lobate scarps.” Scientists aren’t sure why they look this way; perhaps it’s the way the lunar soil — regolith — expresses thrust faults, according to Watters.

Lobate scarps are found on other worlds in our solar system, including Mercury, where they are much larger. “Lobate scarps on Mercury can be over a mile high and run for hundreds of miles,” said Watters. Massive scarps like these lead scientists to believe that Mercury was completely molten as it formed. If so, Mercury would be expected to shrink more as it cooled, and thus form larger scarps than a world that may have been only partially molten with a relatively small core. Our Moon has more than a third of the volume of Mercury, but since the Moon’s scarps are typically much smaller, the team believes the Moon shrank less.

Because the scarps are so young, the Moon could have been cooling and shrinking recently, according to the team. Seismometers placed by the Apollo missions have recorded moonquakes. While most can be attributed to things like meteorite strikes, Earth’s gravitational tides, and day/night temperature changes, it’s remotely possible that some moonquakes might be associated with ongoing scarp formation, according to Watters. The team plans to compare photographs of scarps by the Apollo Panoramic Cameras to new images from LRO to see if any have changed over the decades, possibly indicating recent activity.

While Earth’s tides are most likely not strong enough to create the scarps, they could contribute to their appearance, perhaps influencing their orientation, said Watters. During the next few years, the team hopes to use LRO’s high-resolution Narrow Angle Cameras (NACs) to build up a global, highly detailed map of the Moon. This could identify additional scarps and allow the team to see if some have a preferred orientation or other features that might be associated with Earth’s gravitational pull.

“The ultrahigh resolution images from the NACs are changing our view of the Moon,” said Mark Robinson from Arizona State University in Tempe, Arizona. “We’ve not only detected many previously unknown lunar scarps, we’re also seeing much greater detail on the scarps identified in the Apollo photographs.”