Rosetta flew past Lutetia at a distance of 1,969 miles (3,168 kilometers) in July 2010, en route to its 2014 rendezvous with its target comet.

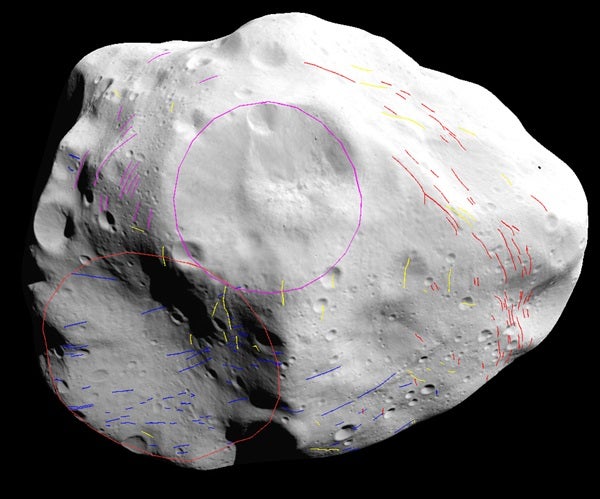

The spacecraft took images of the 60-mile-wide (100km) asteroid for about two hours during the flyby, revealing numerous impact craters and hundreds of grooves all over the surface.

Impact craters are commonly seen on all solar system worlds with solid surfaces, recording an intense history of collisions between bodies. However, grooves are much less prevalent. To date, they have been discovered by visiting spacecraft only on the martian moon Phobos and the asteroids Eros and Vesta.

The way in which grooves are formed on these bodies is still widely debated, but it likely involves impacts. Shock waves from the impact travel through the interior of a small porous body and fracture the surface to form the grooves.

“For Lutetia, by assuming that the grooves were formed in concentric patterns around their source impact crater, we identified 200 such features falling into distinct ‘families,’ correlated with three different impact craters,” said Sebastien Besse from ESA’s Technical Center (ESTEC) in the Netherlands.

One of the groove systems on Lutetia is associated with the Massilia Crater and another with the North Pole Crater Cluster, which comprises a number of superimposed craters. Both are on the asteroid’s northern hemisphere.

But another group of grooves points to a crater not seen during Rosetta’s brief flyby in the asteroid’s southern hemisphere.

Its implied presence has earned it the nickname “Suspicio.” The grooves related to Suspicio cover a large area on the asteroid, suggesting it may span several tens of kilometers . By comparison, Massilia, the largest known crater on Lutetia, is about 34 miles (55km) wide, and the largest of the polar cluster is about 21 miles (34km) across.

“These three major impacts seriously deformed Lutetia’s surface,” said Sebastien.

“As with grooves seen on other asteroids that may also be associated with impact events, this study provides new insights into the catastrophic history of these small bodies.”

By observing how subsequent small craters lie over the grooves on Lutetia, the scientists determined the relative ages of the three larger cratering events. Massilia is thought be the oldest of the three craters and the polar cluster the youngest, with Suspicio between.

The authors also looked at other independent measurements of Lutetia, including ground-based observations with the Infrared Telescope Facility and space-based observations with ESA’s Herschel and NASA’s Spitzer.

Shape models derived by Herschel and Spitzer before Rosetta’s flyby had already predicted a large depression at the location of Suspicio. The Infrared Telescope Facility suggested different compositions between the northern and southern hemisphere of the asteroid.

Sebastien and his colleagues propose that a large impact, presumably the one forming Suspicio, excavated enough material of a different composition to account for the observed differences.

“Our study ties together several independent analyses of Lutetia into one coherent story that is consistent with the presence of a large impact crater on the far side of the asteroid,” said Michael Küppers from ESA’s Space Astronomy Centre in Spain.

“Four years on, and we are delighted still to be learning from just two hours’ worth of data collected during the Lutetia flyby,” said Matt Taylor from ESA.

“Rosetta is now in its main mission phase at its comet, where we are on the cusp of fantastic results. Rosetta is a true small-bodies mission, two asteroids and one comet in a single trip.”