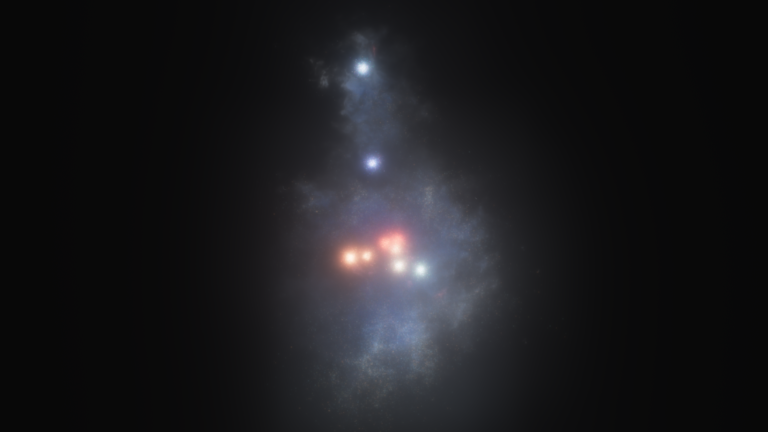

The image also reveals many other galaxies forming the Virgo Cluster, of which M87 is the largest member. In particular, the two galaxies at the top right of the frame are nicknamed “the Eyes.”

Astronomers expect that galaxies grow by swallowing smaller galaxies. But the evidence is usually not easy to see — just as the remains of the water thrown from a glass into a pond will quickly merge with the pond water, the stars in the infalling galaxy merge in with the similar stars of the bigger galaxy leaving no trace.

But now a team of astronomers led by Alessia Longobardi at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching, Germany, has applied a clever observational trick to clearly show that the nearby giant elliptical galaxy M87 merged with a smaller spiral galaxy in the last billion years.

“This result shows directly that large, luminous structures in the universe are still growing in a substantial way — galaxies are not finished yet!” said Alessia Longobardi. “A large sector of Messier 87’s outer halo now appears twice as bright as it would if the collision had not taken place.”

M87 lies at the center of the Virgo Cluster of galaxies. It is a vast ball of stars with a total mass more than a million million times that of the Sun, lying about 50 million light-years away.

Rather than try to look at all the stars in M87 — there are literally billions, and they are too faint and numerous to be studied individually — the team looked at planetary nebulae, the glowing shells around aging stars. Because these objects shine brightly in a specific hue of aquamarine green, they can be distinguished from the surrounding stars. Careful observation of the light from the nebulae using a powerful spectrograph can also reveal their motions.

Just as the water from a glass is not visible once thrown into the pond — but may have caused ripples and other disturbances that can be seen if there are particles of mud in the water — the motions of the planetary nebulae, measured using the FLAMES spectrograph on the VLT, provide clues to the past merger.

“We are witnessing a single recent accretion event where a medium-sized galaxy fell through the center of M87, and as a consequence of the enormous gravitational tidal forces, its stars are now scattered over a region that is 100 times larger than the original galaxy!” said Ortwin Gerhard, also from the Max Planck Institute.

The team also looked carefully at the light distribution in the outer parts of M87 and found evidence of extra light coming from the stars in the galaxy that had been pulled in and disrupted. These observations have also shown that the disrupted galaxy has added younger bluer stars to M87, so it was probably a star-forming spiral galaxy before its merger.

“It is very exciting to be able to identify stars that have been scattered around hundreds of thousands of light-years in the halo of this galaxy — but still to be able to see from their velocities that they belong to a common structure. The green planetary nebulae are the needles in a haystack of golden stars. But these rare needles hold the clues to what happened to the stars,” said Magda Arnaboldi from ESO in Garching, Germany.