This contingency plan — known as in situ resource utilization — is not only necessary to reduce global warming, but could even be key to our continued growth as a species, according to Phil Metzger, a planetary scientist at the University of Central Florida. Before that, Metzger spent 30 years at NASA where he cofounded Swamp Works, a lab that develops tech for space mining and interplanetary living.

“The solar system can support a billion times greater industry than we have on Earth,” Metzger says. “When you go to vastly larger scales of civilization, beyond the scale that a planet can support, then the types of things that civilization can do are incomprehensible to us … We would be able to promote healthy societies all over the world at the same time that we would be reducing the environmental burden on the Earth.”

Unless there are breakthroughs in quantum computing, Earth won’t be able to produce enough energy to power the world’s computers by 2040, according to a 2015 report from the Semiconductor Industry Association. The raw materials for solar panels and wind turbines could also dry up as our supplies of rare earth metals dwindles.

Meanwhile, asteroids and other cosmic bodies are ready sources of metals and other precious resources, and often contain the ingredients of rocket fuel. And moving industry to space would mean moving those emissions off-world as well. For many forward-looking entrepreneurs and scientists, space industry is beginning to look like an inevitability.

Space, Inc.

When Angel Abbud-Madrid joined the Colorado School of Mines as a professor in 1999, the school began hosting an annual “space resources roundtable,” a get-together for space professionals, economists, policy analysts, and members of the mining and metals industry to discuss the value of space mining. After all, the supplies of precious metals contained in asteroids, such as platinum, cobalt and ruthenium, are nearly endless.

If it were possible to bring some of these valuable materials down to Earth, would it be profitable?

“We concluded that was not the case,” says Abbud-Madrid, director of the Center for Space Resources at Mines. It’s still cheaper to mine for gold and iridium on Earth. But about seven years ago, something changed. Companies like Shackleton Energy and Deep Space Industries began coming to these roundtables to discuss asteroid mining.

“It was a little bit strange to hear,” Abbud-Madrid recalls. “And then we start seeing more companies coming in: South Korea, Japan, India, Russia started getting into this activity about three or four years ago. Luxembourg, a tiny country in Europe, invested heavily in space resources.”

Last fall, the U.S. Geological Survey also started taking the idea of space mining seriously. The sea change came from the spaceflight industry. The cost of going to space has dropped dramatically and the industry began giving the idea of mining resources to build infrastructure in space, rather than bringing them back to Earth, more thought.

“The question is, are things off the Earth going to become economically viable fast enough, so that we can move the industry off the Earth fast enough to prevent all of the environmental damage?” Metzger says.

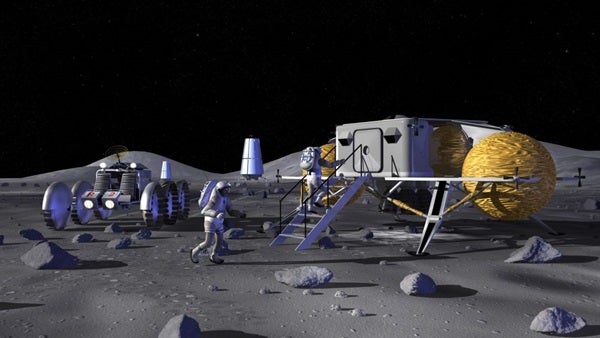

But Abbud-Madrid says we’re nowhere near moving industry into space. Right now, it’s about laying the groundwork by enabling commercial activity and exploration in space, he says. But soon, should technology keep pace with ambition, we could start getting into some scenarios that seem truly sci-fi.

Interplanetary Supply Chain

In 2014, a Silicon Valley startup known as Made In Space, Inc. became the first company to 3D print an object in zero gravity. “This first print is the initial step toward providing an on-demand machine shop capability away from Earth,” Niki Werkheiser, project manager for the International Space Station 3-D Printer, said at the time in a press release.

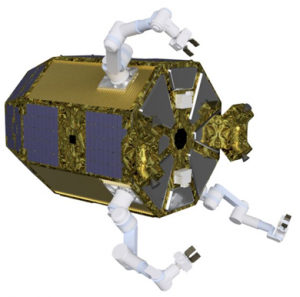

But autonomous robots could not only build spacecraft in space, they could undertake other essential tasks like harvesting fuel and beaming solar energy back to Earth.

By concentrating lasers on asteroids, spacecraft would kick up water ice that can be collected and broken down into hydrogen and oxygen — the ingredients for a type of rocket fuel. NASA recently awarded the aerospace corporation Trans Astronautica a grant for a solar powered robotic spacecraft based on this design, but the work is still in the early stages.

We also may be able to shut down earthly power plants by moving them to low-Earth orbit. In space, solar power wouldn’t be limited by pesky things like clouds or darkness — solar panels can harvest power indefinitely, then beam it to your house using microwaves. This tech could be essential for future lunar bases.

“The technology to collect sunlight … and beam it to the surface using microwaves is available today,” Les Johnson, a scientist at NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, wrote in 2017. China, India, Japan, and the European Union have been exploring the concept for several years, though NASA doesn’t have plans for such a project.

From the Moon, to Mars and Beyond

As we look beyond Earth for resources and fresh opportunities, another problem looms. Testing and building technology in space may actually be the easy part of the equation — the more problematic concerns might be political and social. If certain countries get to space resources first, they could monopolize them, worsening wealth inequalities here on Earth.

“Building an infrastructure for the growing space economy will require considerable engineering, technological and scientific talent,” says Danielle DeLatte, a senior space systems engineer at Draper Laboratory. “But to ensure equitable access to space and a common understanding of our various science and mission priorities, emerging space countries, companies and key stakeholders must be included from the beginning.”

But we may be racing against the clock. Earth’s natural resources will not last forever, and if they run out, we could be grounded here forever. And perhaps bringing some of the most destructive practices on Earth — mining and fossil fuel extraction — out to space isn’t a good thing. Last month, two researchers called for designating nearly 90 percent of the solar system a protected “wilderness” area.

“We have no good reason to believe that such an off-world economy would behave in a radically different way from terrestrial economies,” they argued. “Once we have exploited our solar system, there is no other plausible and accessible new frontier.”