Astronomers unveiled a new survey that gives an unprecedented view of the inner regions of our home galaxy, the Milky Way. These regions are peppered with thousands of previously undiscovered dense knots of cold cosmic dust — the potential birthplaces of new stars.

The survey was produced from observations with the Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX) telescope in Chile and its Large Apex Bolometer Camera LABOCA, the newest and biggest format in a series of Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy (MPIfR) built bolometer cameras used on (sub)millimeter telescopes. This is the largest map of cold dust so far at wavelengths shorter than 1 millimeter, and it will provide an invaluable target list for observations made with the forthcoming Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA), as well as the recently launched European Space Agency’s (ESA) Herschel Space Observatory.

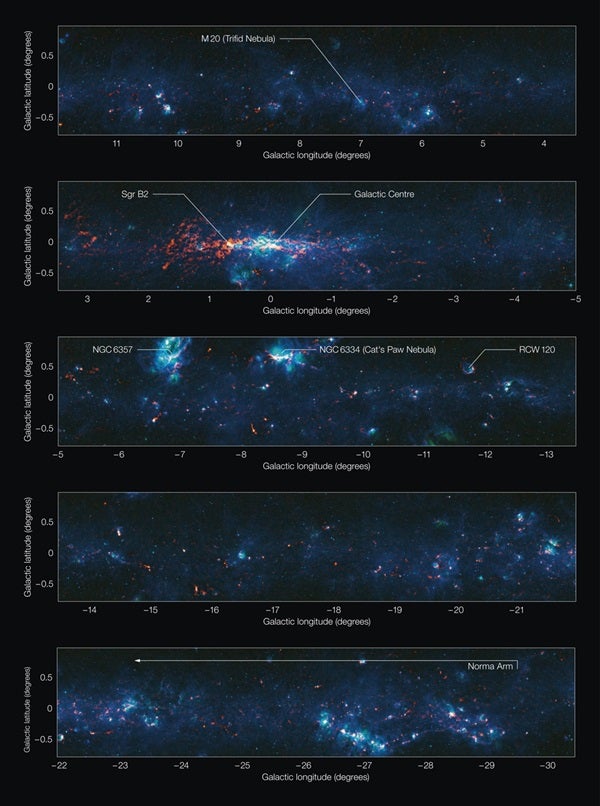

This new guide for astronomers, known as the APEX Telescope Large Area Survey of the Galaxy (ATLASGAL) shows the Milky Way’s emission at sub-millimeter-wavelengths (between those of infrared light and radio waves). Images of the cosmos at these wavelengths are vital for studying the birthplaces of new stars and the structure of the crowded galactic core.

“Not only will ATLASGAL help us investigate how massive stars form, but it will also give us an overview of the larger-scale structure of our galaxy,” said Frederic Schuller from MPIfR, leader of the ATLASGAL team.

The area of the new sub-millimeter map is approximately 95 square degrees, covering a very long and narrow strip along the galactic plane 2° wide (four times the width of the Full Moon) and more than 40° long. The 16,000 pixel-long map was made with the LABOCA sub-millimeter-wave camera on the ESO-operated APEX telescope. APEX is located at an altitude of 16,700 feet (5,100 meters) on the arid plateau of Chajnantor in the Chilean Andes — a site that allows optimal viewing in the sub-millimeter range.

The interstellar medium — the material between the stars — is composed of gas and grains of cosmic dust, rather like fine sand or soot. However, this gas is mostly hydrogen and relatively difficult to detect, so astronomers often search for these dense regions by looking for the faint heat glow of the cosmic dust grains.

Sub-millimeter light allows astronomers to see these dust clouds shining, even though they obscure our view of the universe at visible light wavelengths. Accordingly, the ATLASGAL map includes the denser central regions of our galaxy, in the direction of the constellation Sagittarius, that are otherwise hidden behind a dark shroud of dust clouds.

The newly released map reveals thousands of dense dust clumps, many never seen before, that mark the future birthplaces of massive stars. The clumps are typically a couple of light-years in size and have masses of between 10 and a few thousand times the mass of our Sun, enough to give birth to stars or even clusters of stars. In addition, ATLASGAL shows diffuse emission connecting these clumps and has captured images of beautiful filamentary structures and bubbles in the interstellar medium, blown by supernovae and the winds of bright stars.

The photo shows in comparison the star forming clouds and complexes as observed in ATLASGAL, together with hotter dust of more evolved young stars still embedded in their dust cocoons, as observed in the Midcourse Space experiment (MSX) at infrared wavelengths.

Some striking highlights of the map include the center of the Milky Way, the nearby massive and dense cloud of molecular gas called Sagittarius B2, and giant star forming complexes like NGC 6357 and NGC 6334, the Cat’s Paw Nebula.

“Every single compact source in the ATLASGAL survey shows us a place at which new stars are presently being formed,” said Karl Menten, APEX principal investigator, director at MPIfR, and team member of the ATLASGAL project. “We just have to point APEX or Herschel and, in the future, ALMA towards these positions to observe the molecules associated with the dust to get a full picture of star formation throughout our Milky Way.”