New observations from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter indicate that the crust and upper mantle of Mars are stiffer and colder than previously thought.

The findings suggest any liquid water that might exist below the planet’s surface, and any possible organisms living in that water, would be located deeper than scientists had suspected.

“We found that the rocky surface of Mars is not bending under the load of the north polar ice cap,” says Roger Phillips of the Southwest Research Institute. Phillips is the lead author of a new report appearing in this week’s online version of Science. “This implies that the planet’s interior is more rigid, and thus colder, than we thought before.”

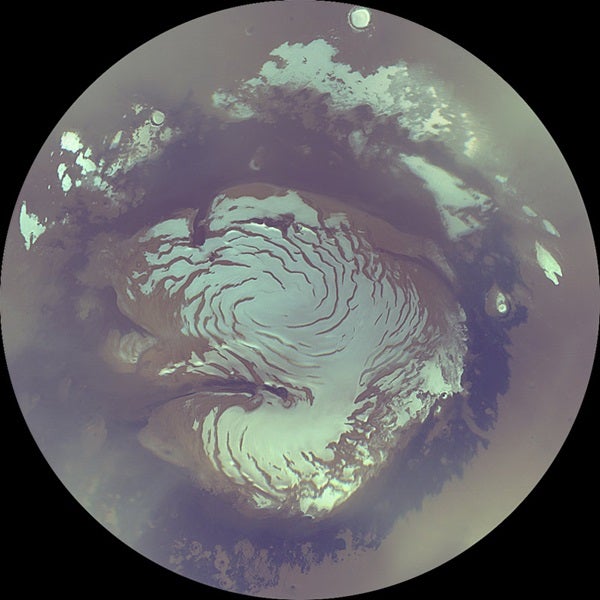

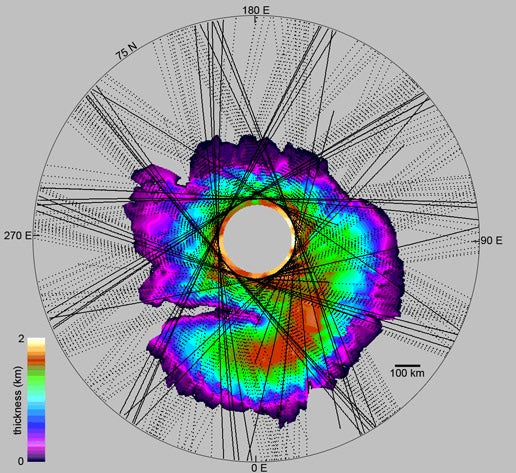

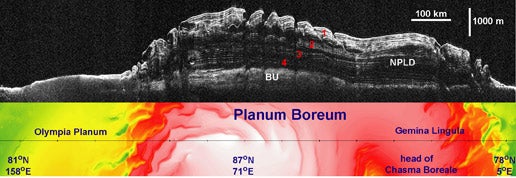

The discovery was made using the Shallow Radar instrument on the spacecraft, which has provided the most detailed pictures to date of the interior layers of ice, sand and dust that make up the north polar cap on Mars. The radar images reveal long, continuous layers stretching up to 600 miles (1,000 kilometers), or about one-fifth the length of the United States.

The radar pictures show a smooth, flat border between the ice cap and the rocky martian crust. On Earth, the weight of a similar stack of ice would cause the planet’s surface to sag. The fact that the martian surface is not bending means that its strong outer shell, or lithosphere—a combination of its crust and upper mantle—must be very thick and cold.

“The lithosphere of a planet is the rigid part. On Earth, the lithosphere is the part that breaks during an earthquake,” says Suzanne Smrekar, deputy project scientist for Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter at JPL. “The ability of the radar to see through the ice cap and determine that there is no bending of the lithosphere gives us a good idea of present day temperatures inside Mars for the first time.”

The radar pictures also reveal four zones of finely spaced layers of ice and dust separated by thick layers of nearly pure ice. Scientists think this pattern of thick, ice-free layers represents cycles of climate change on Mars on a time scale of roughly one million years. Such climate changes are caused by variations in the tilt of the planet’s rotational axis and in the eccentricity of its orbit around the sun. The observations support the idea that the north polar ice cap is geologically active and relatively young, at about 4 million years.

On May 25, NASA’s Phoenix Mars Lander is scheduled to touch down not far from the north polar ice cap. It will further investigate the history of water on Mars, and is expected to get the first up-close look at ice on the Red Planet.